Kim Dae Jung (1945-2009)

In a 1985 interview with me at his home in Seoul, the future president and then-opposition leader spoke for the first and only time about the U.S. role in Korea during the Gwangju Uprising of 1980.

Credit: Yonhap News Agency, via Reuters, NYT.

Kim Dae Jung was a great man. As South Korea’s leading opposition politician during the years of authoritarian rule under Park Chung Hee and Chun Doo Hwan, Kim fought courageously for democracy and was nearly killed by the government – not once but twice. Despised and distrusted by the United States for his progressive views on Korean unification and South Korea’s place in the world, he triumphed over adversity in 1997 when he was finally elected president.

I first met him in the 1980s, when he was in exile in Boston and Washington after escaping Chun’s executioners in 1981. Four years later, I met him in Seoul just after he returned to Korea, where he was immediately put under house arrest. One day, after arranging an interview through his aides, I walked through the cordon of security police surrounding his house and spent the next two hours talking over lunch – just me and him. He remembered me well from Washington.

In this interview, he spoke for the first and only time in public about the Gwangju Uprising and the U.S. role in his country in 1979 and 1980. His words about President Carter’s mistaken policies stayed with me:

The Kwangju people kept order; paratroopers broke order…You should have criticized the paratroopers’ side, not the Kwangju people’s side. Your attitude was not just, not fair.

_____________________

AN INTERVIEW WITH KIM DAE JUNG

As published in The Progressive, February 1986

Kim Dae Jung, South Korea’s best-known dissident, was imprisoned and sentenced to death for treason in 1980 on trumped-up charges of instigating the Kwangju Uprising. Freed in 1981 after strong pressures from around the world, he moved to the United States, where he spent four years writing and lecturing. Last year, with former political rival Kim Young Sam, he organized the Council to Promote Democracy and returned to South Korea to rejoin the democratic movement.

Though hated by the Korean military, Kim is basically a conservative. Many dissidents mistrust him, fearing that he may put his political ambitions above the broader needs of the opposition. They also criticize what they consider to be his pro-American attitude. But his courageous struggle against military rule has also earned him widespread admiration and respect.

I interviewed Kim last June, a month before he was placed under house arrest again. Here are some excerpts from our conversation:

Q: Was the United States responsible for the Kwangju Uprising and its bloody suppression?

A: You dispatched a Korean division to Kwangju to keep order, but before sending troops, you should have examined which side was keeping order – the Kwangju people or the paratroopers. The Kwangju people kept order; paratroopers broke order. They massacred peaceful demonstrators. They massacred many young men after binding them. Their hands were bound by their sides, but they were killed. They were unable to fight. So you should have criticized the paratroopers’ side, not the Kwangju people’s side. Your attitude was not just, not fair.

If America had not sent one division to Kwangju, Chun Doo Hwan would not have succeeded in getting power. If the Americans didn’t support that paratroopers’ massacre, then our people would have risen up for democracy in other cities. We could have succeeded in restoring democracy. Chun was not so strong then; he was not supported by our people. Only America supported him.

Q: Do you favor the withdrawal of the 40,000 US troops stationed in South Korea?

A: In the future, we can realize strong security because we can enjoy the people’s voluntary support also force North Korea to have a sincere dialogue to bring peace to the Korean peninsula. We would raise conditions for a permanent peace treaty to ask American troops to withdraw from South Korea. But at the present, it is too early for us to ask for the withdrawal of American troops from South Korea because there is no strong security under dictatorial rule. The dictatorial government fails to get the people’s voluntary and full support.

Q: What kind of economic system would you like to see in South Korea?

A: Well, we are supporting the free-market system. We never want to damage our ability to promote exports. So we don’t support any laborer’s request to ask a higher wage compared to promotion of productivity. On the other hand, our country has for more than ten years promoted exports on the international market with a low wage. But the low-wage era has passed. There is the Chinese competition – they are competing with Korea at a far lower wage. So we must escape the need for such an era.

Now we are seeking high-technology production. To succeed in such a high-tech era, we must liberate two groups; one is businessmen. In this country, all businessmen are under government control. Even though they have become rich men, there is no freedom of businessmen. We must liberate them so we can have free competition and fair competition. And also we must liberate our laborers from suppression. Only when laborers are active and willing to produce very good quality goods can we succeed in high-technology.

Q: How unified is the opposition movement?

A: The democratic movement is well unified. Kim Young Sam and I are maintaining close cooperation – no split. And we are seeking a very healthy common goal: Western-style democracy, a free-market system, and supporting the rights of consumers and laborers. We are seeking a very prudent social-welfare system. And we support the national security. We criticize America and Japan, but we don’t want to become anti-American and anti-Japanese.

Q: How hopeful are you that democracy will return to South Korea?

A: I am carefully hopeful. But whether we can reach our democracy easily and peacefully may depend on whether we can avoid military involvement in politics or not – and that depends mainly on the American commander’s attitude. As long as the American military commander has the right to control all Korean military forces of 600,000 troops, the American commander must take the responsibility to prevent military involvement in a coup.

You know, when there was the Korean War thirty years ago, there was democracy – in wartime. We had freedom of speech, local autonomy, direct election of the president, the independence of the national assembly and the judicial branch. But at peacetime now, we have lost all of those freedoms. In wartime, our people’s per-capita income was only $16; now it has soared to $2,000. But we can’t enjoy the same freedom we had when it was $16. How can we understand that?

Thoughts on Kim Dae Jung at the time of his death in 2009

Kim Dae Jung, South Korea’s most famous dissident and former president, is dead.

By Tim Shorrock

On August 18, 2009, Kim Dae Jung, the former president of South Korea and that nation’s leading dissident during its long period of military dictatorship, died in Seoul of heart failure.

News of Kim’s death came as a shock to millions of Koreans, north and south. For decades, Kim had stood almost alone as a symbol of the deep Korean desire for democracy and independence, and was revered on both sides of the border for his commitment to unification and reconciliation between the two Koreas.

As a journalist who has written extensively about Korea for the past 30 years, I too was deeply saddened by Kim’s passing. My feelings were shaped in part by my personal experience with Kim, whom I had met several times during his years of exile in Washington in the early 1980s.

During that time, I worked closely with a faith-based coalition that sought to focus public and congressional attention on South Korea and the deep ties between its authoritarian leaders and the U.S. military. Kim spoke to the coalition several times, giving his impressions of US-Korean ties and how they could be improved.

KIM’S OPTIMISM

Two things struck me about Kim during our meetings. One was his deep Christian faith and his boundless optimism about the possibility of change. Even in the darkest days of the military dictatorship, he expressed a strong belief that democracy would be restored to South Korea. Many supporters found that concept hard to embrace, given the enormous US military presence there and the huge US economic stake in South Korean industry and trade.

The other was his love for America and his profound faith that the American people and their leaders would eventually do the right thing in Korea. Sometimes I thought he was incredibly naïve: throughout the Cold War, the US government had supported savagely repressive governments, such as Chile’s after 1973 and Indonesia’s after 1965, in the name of national security, and did it for decades in South Korea. At the same time, Kim for years was the subject of a vicious campaign of slander by US officials who portrayed him as a dangerous and unbalanced leftist. To me, it seemed incredibly unrealistic to think that would ever change. But it did, and Kim turned out to be right on many fronts.

My fondest memory of Kim Dae Jung is from 1985, when I met him at his home, shared a traditional (and delicious) Korean meal, and sat down for an extensive interview. I had just spent several weeks in South Korea meeting with student and labor activists, and was there to write about the growing movement against the US-supported dictatorship of Lt. Gen. Chun Doo Hwan, who had seized power in a violent coup in May 1980. During my visit, I had spent several days in Kwangju, Kim’s home town and the site of the infamous Kwangju Massacre, when hundreds of students and workers were gunned down and bayoneted to death for standing up to Chun’s coup (details from my reporting can be found in the PDF of my Progressive article, “Korea: Stirrings of Resistance.”)

All of this was very personal for Kim, who was arrested in the wake of the massacre, charged with organizing the uprising, and sentenced to death. In December 1980, Chun spared Kim’s life as part of deal in which his illegitimate government was recognized by the incoming Reagan administration (Chun was Reagan’s first official state visitor to the White House). Kim was released in 1981, and spent the next four years in the United States before returning to Seoul in 1985.

My interview with him was thus critical to my work. When I met him in June 1985, his home was surrounded by military police and his freedom of movement greatly restricted. In the days leading up to the interview, I had witnessed several clashes between student activists and riot police, and my clothes still reeked of the vicious pepper fog used by the cops to disperse crowds.

MY LUNCHEON WITH KIM

The day I met with Kim, he was in a great mood despite the security cordon around his house in central Seoul. To my surprise, he remembered me. During one of his talks in Washington, I had asked him about his views on nuclear power and the US campaign at the time to pressure the Korean government to buy power plants from the US companies Westinghouse and Bechtel. He hadn’t said much in reply – and Kim told me, with a laugh, that I had probably been disappointed in his answer.

I had been; but I was definitely not disappointed with what Kim told me in our interview that day. For the first (and only) time, Kim addressed the sensitive issue of Kwangju and the manner in which the Carter administration, led by Richard Holbrooke, then the Assistant Secretary of State for Asian and Pacific Affairs, had responded to the tragedy.

Essentially, Carter and Holbrooke – enthusiastically backed by Carter’s national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski – saw the Kwangju incident as a threat to the US-South Korean military relationship and therefore something that threatened vital American interests. At the height of the crisis, as I’ve described in articles based on declassified documents from the time, the Carter administration decided not to break with the Chun regime and instead tried – and failed – to coax a group of military gangsters into democratic reform. Military and economic aid continued, and the people of Kwangju were dismissed as “radicals” and “extremists” who had brought the calamity on themselves. It was a disgraceful performance, and persuaded many Koreans that America could never be trusted again.

Kim Dae Jung knew first-hand what had happened to his compatriots, and in our interview that day expressed deep anger about what had occurred in Kwangju. He publicly criticized the US government for its unequivocal support for the Chun military group and equated that backing to “supporting” the massacre. By releasing a division from the combined US-South Korean command to put down the uprising in Kwangju, he argued, the Carter administration allowed Chun to take power.

“If America had not sent one division to Kwangju, Chun Doo Hwan would not have succeeded in getting power,” he said. “If the Americans didn’t support that paratroopers’ massacre, then our people would have risen up for democracy in other cities. We could have succeeded in restoring democracy.”

In our interview, Kim also laid out his vision for a future, democratic South Korea and expressed his deep hopes for reconciliation with the North. “In the future, we can realize strong security because we can enjoy the people’s voluntary support and also force North Korea to have a sincere dialogue to bring peace to the Korean peninsula,” he told me.

PEACE TREATY FIRST, THEN US TROOPS CAN EXIT

Kim was very direct about the role of American forces in his country. They needed to be in South Korea then, he said, because “there is no strong security under dictatorial rule.” But once there was peace, he insisted, the need for US forces would disappear. “We would raise conditions for a permanent peace treaty to ask America troops to withdraw from South Korea.”

Much of Kim’s vision became reality, and he died knowing that the people of Kwangju had been vindicated and the threat of war between North and South Korea greatly diminished. But nearly 30,000 US troops remain in South Korea and a US commander remains in control of Korean forces in times of war – making South Korea the only country in the world where a foreign army exerts such influence. As the recent clash between the North and South Korean navies illustrates, we’re still a long way from peace and reconciliation in Korea.

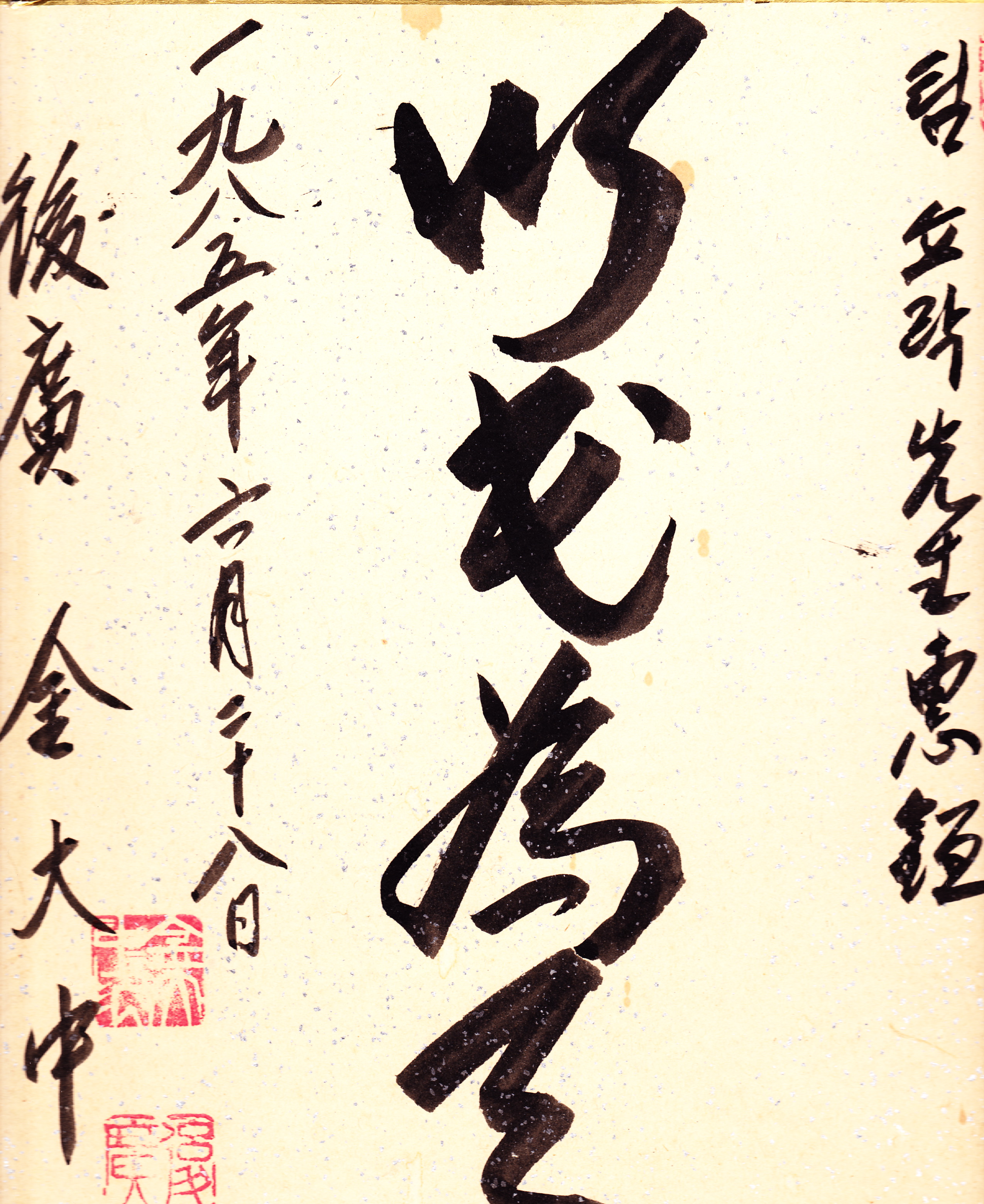

Still, Kim’s vision remains. I’m proud to have known this great fighter for democracy, and will always treasure the Chinese calligraphy he wrote for me that long ago day:

To care for the People

As if They were Heaven.