What is the DMZ Empire?

By Tim Shorrock

The Demilitarized Zone that surrounds the truce village of Panmunjom extends 625 miles across the Military Demarcation Line that divides the Korea peninsula into two hostile states. It is one of the saddest places on earth, marking the last stand of the US-and communist-led armies that battled it out in this mountainous land from 1950 to 1953 in one of the most vicious wars in modern history.

I first visited the DMZ in October 1960, not long after my father moved our family to Seoul to run the Korea division of Church World Service, America’s largest private relief organization. Then as now, the DMZ was a scary and moving sight, with the sharp, barbed-wire fences on the border country covered with brightly colored ribbons displaying plaintive messages from Koreans yearning for peace and unification with their long-lost families and relatives in the forbidden North.

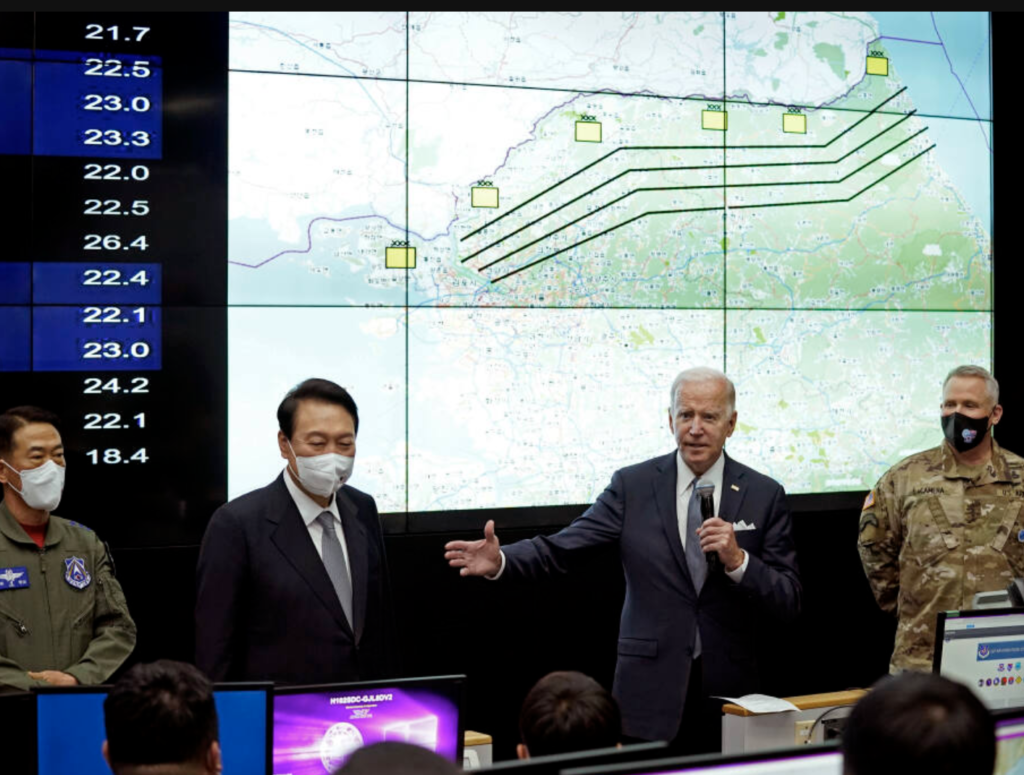

To most Americans, however, the DMZ is a symbol of US military might – the perfect backdrop for American dignitaries eager to show their determination to defend their “free world” from the evils of communism. Joe Biden first made the trek as a Senator in 2001 and later as vice president in 2013. During his first trip to Korea as president last May, he skipped the border shot and went instead to Osan Air Base, where he was briefed on the military situation by US Air Force commanders. “You are the front line, right in this room,” Biden told them. “We are prepared for anything North Korea does.”

This has been so since the war ended in an armistice in 1953. Despite 70-plus years by Washington of strenuous military preparations, North Korea today fields the world’s fourth largest army and is armed with nuclear weapons and guided missiles capable of hitting the continental United States.

Yet the United States is not, and has never been, an innocent bystander in Korea. It was the United States that suddenly, and unilaterally, divided Korea in the summer of 1945 and claimed its southern half a U.S. military protectorate. US forces have been there ever since, and in massive numbers, since the end of the Korean War and its signing in 1954 of a mutual security treaty with the ROK.

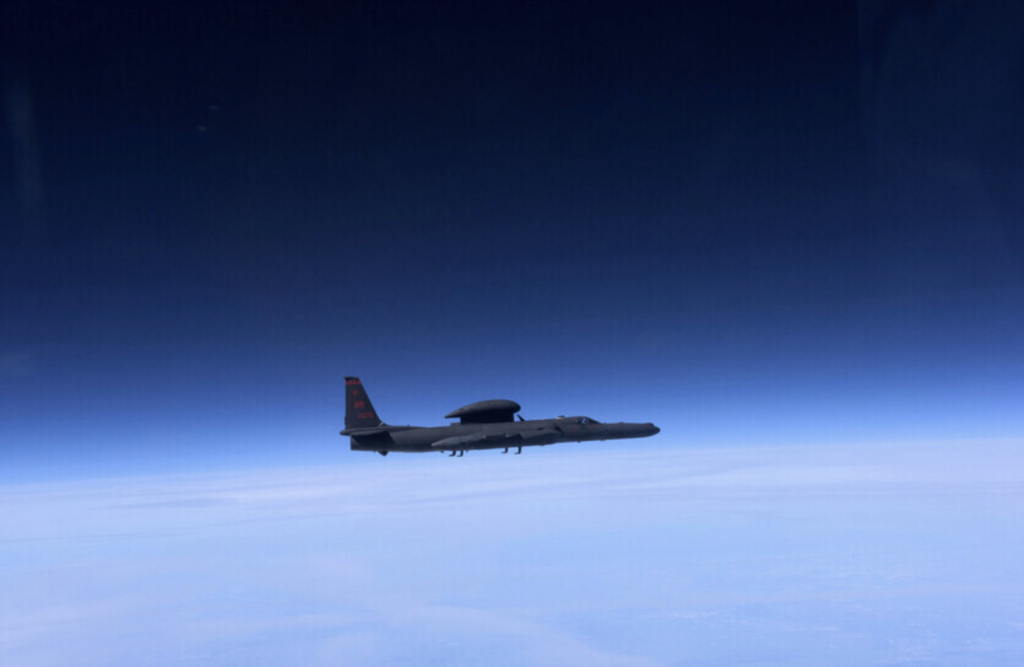

Today, 80 miles south of the DMZ, the Pentagon operates Camp Humphreys, its largest military base outside of North America. It is headquarters for the 600,000-strong US-South Korean Combined Forces Command created in 1978. Across the East Sea, the US military stations over 75,000 soldiers in bases from Hokkaido to Okinawa, with the latter hosting US intelligence bases and Marine outposts that provide critical support to the US-run United Nations Command in Korea (they are known as the UN Command-Rear). All of these forces are augmented by the giant Anderson Air Force Base in Guam, where nuclear-armed B-1B and B-52 bombers are at the ready 24/7. The “enemy” of these US-led forces has evolved from their initial focus on North Korea and the Soviet Union to China, which is today seen by the Pentagon as an even greater long-term threat to US national security interests than the USSR of the Cold War.

I call the massive U.S. military fortress in East Asia the “DMZ Empire.”

It is based, first and foremost, on the permanent division of Korea at the DMZ; moreover, the United States has formally recognized since 1969 that the maintenance of “stability” in South Korea as “essential” to Japan’s security. My Patreon (as illustrated in my cover picture), this website, and my next book, will be devoted to laying out the history of this DMZ empire and its role in the ongoing Korean War, which has never formally ended and remains American’s longest military conflict.

The book I’m writing is the direct result of my experience in Asia. As the eldest son of two American missionaries to Japan and South Korea during the Cold War, I had a unique view into the U.S. military occupations of Southern Korea and Japan and the formation of the military alliance that I define as the DMZ empire.

In both Japan and South Korea, my dad played a key role in the U.S. civilian side of relief and reconstruction as regional director of Church World Service, America’s largest private relief organization. In postwar Japan, he often worked in cooperation with the US military and its occupation forces, while in Korea he reported directly to the US embassy, then running the massive US aid program to Korea at that time. In certain ways, CWS, which provided healthy profits to America’s largest Protestant churches for over 60 years, was the forerunner of today’s contractors who dominate the private space in the military’s management of “conflict zones” – rather ironic considering I wrote the first and only history of intelligence privatization in Spies for Hires.

During my family’s years in Asia, momentous change and revolution came to the region – and then a lurch into full-scale militarism. Before, during, and after the Korean War, the United States built the South Korean military (whose officer corps was almost entirely trained by the Imperial Japanese) into one of the world’s largest armies. But it always made sure to keep operational control over Korean forces, putting the entire ROK army under the command of a US general.

The trend towards military rather than diplomatic solutions to the Korean situation accellerated in 1958, when the Eisenhower administration and the Pentagon introduced atomic weapons into the peninsula, in artillery, cannons (pictured), aerial bombs, and hand-carried bazookas. This violated the 1953 armistice, but the US plowed on, setting off the nuclear “crisis” that has haunted every US president from Reagan to Biden (the introduction of U.S. nukes, of course, is never considered as a factor in North Korea’s later development of a tiny nuclear arsenal to protect itself. Not even the most popular books about Kim Jong Un’s nukes mention it).

In Japan, the US occupation forces under the command of General Douglas MacArthur used the occasion of the Korean War to restart Japan’s first postwar army (politely called “self defense forces”). In 1952, John Foster Dulles negotiated and signed a treaty that gave the United States the right to operate military bases on Japanese soil more or less forever, and locked Japan into a subordinate military relationship that gives US forces unlimited access to Japanese skies – rights its own citizens and military do not have. Over time, as all three militaries grew in technical strength,

The 50,000 US soldiers now stationed in Japan (mostly in the rebellious, occupied province of Okinawa) make up America’s largest overseas force. Thus, as argued earlier, we have a military empire built on the foundation of a permanently divided Korea (at the DMZ) that’s based historically on the 75-year quest – largely successful – by the United States to reunite the southern half of Korea with its former colonial power, Japan.

That, of course, is what US imperial ideologues like Vice President Kamala Harris mean when they say South Korea is the “anchor” of US power in the Pacific. But while the Japan/Korea nexis is the “linchpin,” so are the dozens of other US military bases and installations, not to mention the blue water Navy, scattered from Okinawa to Guam (home of the regional “strategic bombers”) and Australia.

The continuous US occupation of land for its military needs since 1945 violates the rights of the people of the Asia-Pacific region who have lost their farms to US bases and been exposed to the vast amount of toxic waste – atomic radiation, Agent Orange, napalm, petroleum – the Pentagon has left behind as it has poisoned the Pacific, as Jon Mitchell, the great Welsh journalist in Yokohama, has tracked for decades.

THAT is what I mean by “DMZ Empire.” Get it?

So back to the book, which I’ll be working on over the next year. It requires research. Reams of research. Hours, days, endless weeks, of research, into my parents’ letters from occupation days, the files on postwar Japan and Korea in the National Archives, church records and records of prominent missionaries I knew at the Presbyterian Historical Society’s archives in Philadelphia, the JFK and other presidential libraries. Plus photographs, audio tapes, underground media, old newspapers and magazines, etc. All mixed in with countless interviews I’ve done over the years with … missionaries, gold diggers, soldiers and spies. This is the building material for my book but is also going to be the endless source for my second archive – DMZ Empire/Korea & Japan in America’s Pacific Strategy (1945-2022).