The Troubadour as Teacher

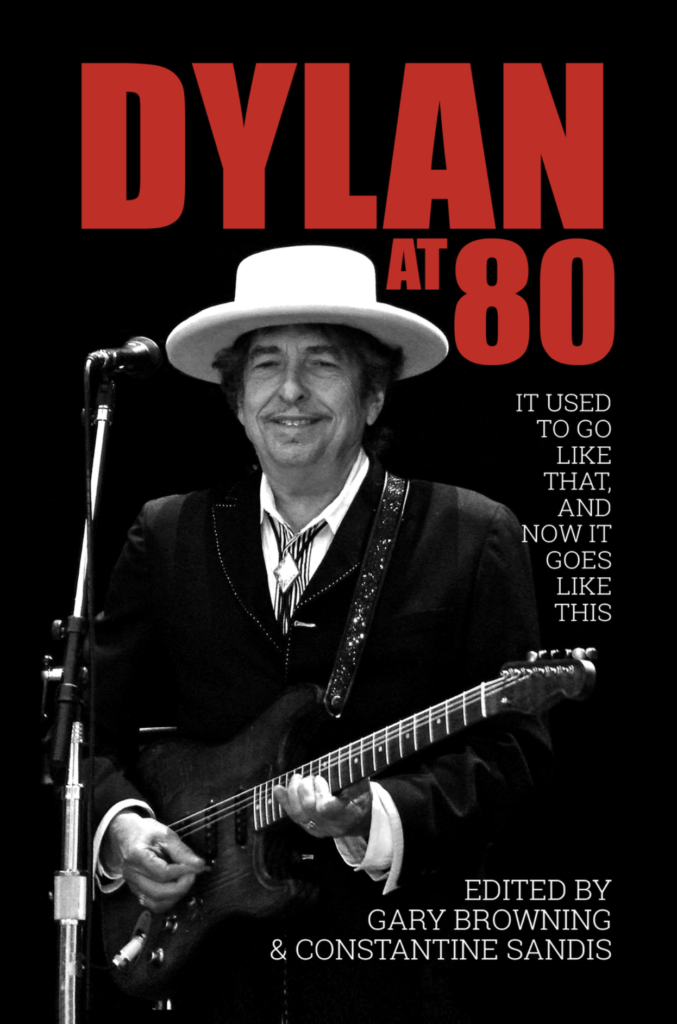

Bob Dylan continues to amaze. At age 81, he is making the best music of his career and still making his way around the world as a troubadour seeped in the depths of American music. I first heard Bob in 1964, when Pete Seeger introduced me to him (in Tokyo) through perhaps his greatest song, A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall. The words completely bowled me over, and I had to find out who he was; I did, and I’ve never looked back. I’ve seen him about 50 times and will go anytime he comes close to DC. Below is my tribute to him at age 80. I wrote this in 2020 and am ever grateful to the book‘s editors, Gary Browning & Constantine Sandis, for inviting my contribution. You can see the video book party here (wonderful in part for the fiddle playing of Scarlett Rivera of Desire fame) and my reading here, which I taped later. I hope you enjoy this as much as I enjoyed writing it!

— Tim Shorrock

By Tim Shorrock

As I look back on Bob Dylan at 80 years old, I’m most struck by his role as a teacher. That phase began for me in 1964, when I first knowingly heard a Dylan song. It was the visionary “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” as performed by Pete Seeger in Tokyo, Japan, where I grew up. I was mesmerized, hooked for life: As Bob would write years later about the Italian poets he loved, “every one of them words rang true, and glowed like burnin’ coal.”

Since the days of my youth, Bob Dylan has taught me a great deal about love, politics, war, culture, music, history, religion, and the full scope of the human condition, from kindness and nobility to treachery and plunder. His work will last for generations as a guidepost to our forgotten past and our uncertain future on this earth. “Wasn’t that a time?” the Weavers sang during the Cold War years when Dylan got his start. It was indeed.

The first insights Dylan passed to me were about America itself. Like many of my fellow contributors, I was raised outside of the United States, and into my early teens knew very little about the political and social realities of the USA. But my eyes were soon opened wide. Not long after Seeger introduced me to Dylan in Japan, a friend just back from living in New York City lent me all of his records up to then, starting with his debut folk album and ending with Bringing It All Back Home. I taped them all onto a Sony reel-to-reel and sat in my room and listened intently, not really knowing which record was which.

As my tapes rolled, visions of America’s dark side of racism, militarism and inequality flew by, juxtaposed against deeply moving songs of love and passion, all of them fueled by fierce guitar strumming and wild harmonica blowing. What I heard was markedly different from the R&B, folk and rock music on the radio back then, and seemed almost from another world. His songs were gritty, soul-crushing and eye-opening. Some were angry, others were mournful. But they were all a direct line into the truth. “I don’t need Time, I don’t need Newsweek,” Dylan mockingly told a London reporter in 1966, in D.A. Pennebaker’s bio-epic Don’t Look Back. Well, I didn’t either; I had Bob. And from him, I heard the news, oh boy.

On The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, one of his greatest songs, he offered the horrifying tale of the racist William Zanzinger, a spoiled child of “rich wealthy parents from the politics of Maryland,” carelessly throwing his cane across a barroom floor and killing “the maid in the kitchen” who “never sat once at the head of the table.” For that, he only got only a six month sentence, so you’d damn well weep now, Dylan told me.

I can still remember the shock I felt upon hearing Ballad of Hollis Brown, Dylan’s story of a broken man on a South Dakota farm who shoots his entire family and himself with a shotgun. It was a deep lesson in poverty and hopelessness in rural America, told through the eyes of the killer himself. Words like these brought shivers: Your baby’s eyes look crazy/They’re a-tuggin’ at your sleeve/Your baby’s eyes look crazy/They’re a-tuggin’ at your sleeve/You walk the floor and wonder why/With every breath you breathe.

Dylan’s use of “you” and “your” gave this song its power. He made me look at the awful situation through the dirt farmer’s own eyes. I felt the terror that must have engulfed him as he realized he was holding a shotgun in his hand and was pulling the trigger, again and again, as “seven shots ring out like the ocean’s pounding roar.” The visceral images helped me understand why he may have done this terrible deed.

Only a Pawn in Their Game had a similar effect. It was all about how beaten-down white men like Hollis Brown were manipulated by the powerful into turning their smoldering anger about the condition of their lives into raging hatred for Black men like Medgar Evers; Dylan bravely played that song at the great Civil Rights March of 1963. The torrent of music that flowed from his brain informed both the past and our painful present.

In North Country Blues, he sang of the poverty and instability caused by capitalists shutting down mines in Minnesota and buying from abroad; you can hear similar words today in the laments of laid-off miners on the Iron Range: They complained in the East/They are paying too high/They say that your ore ain’t worth digging/That it’s much cheaper down/In the South American towns/Where the miners work almost for nothing. There were lots of tunes about coal mining and work back then. But nobody was writing songs like this, linking poverty and joblessness with globalization and the corporate search for cheap labor.

In Masters of War on Freewheelin’, he even took on the military industrial complex. His bitter lyrics still resonate as I seethe inwardly at the cruelty of America’s militarist mindset: You fasten the triggers/For the others to fire/Then you set back and watch/When the death count gets higher/You hide in your mansion/As young people’s blood/Flows out of their bodies/And is buried in the mud. These weren’t “protest” songs, like journalists liked to call them; they were empathy songs. They helped us see the racism and injustice amidst the American dream as something real, something tangible that maybe we could do something about.

Yet, even with this achievement, I think Dylan’s greatest contribution as teacher is what he’s taught us about music. I first became conscious of this role in 1993, on World Gone Wrong. It was his second acoustic collection of the old blues and folk classics that he learned in the coffee shops and clubs of Minneapolis, New York, Boston, and London, and an education unto itself. I’d heard a lot of the songs before, but not the title song and Blood in My Eyes, two haunting ballads about trying to survive and find love in a twisted world of pain and sorrow. I was enthralled and curious about their origins. Luckily, Dylan had included extensive liner notes, a practice from his first few albums on Columbia. He laid it all out for me.

These tunes were “done by the Mississippi Sheiks,” he wrote, “a little known de facto group whom in their former glory must’ve been something to behold. rebellion against routine seems to be their strong theme. all their songs are raw to the bone & are faultlessly made for these modern times (the New Dark Ages) nothing effete about the Mississippi Sheiks.” World Gone Wrong, he added, “goes against cultural policy,” by which he meant “strange things like courage becoming befuddled & nonfundamental. evil charlatans masquerading in pullover vests & tuxedos talking gobbledygook, monstrous pompous superficial pageantry parading down lonely streets on limited access highways. strange things indeed.”

To me, this was truth in a most uncertain time. In 1993, we were two years into the first Gulf War, the start of the “forever wars” of today, and the airwaves were full of images of a new, troubled America – rightwing preachers and dot-com hucksters screaming against the background of smoke and flame billowing from the first bombing of the World Trade Center in Manhattan or the horrific federal attack on the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas. Dylan had denounced the madness in 1991 at the Grammys, when he was presented with a Lifetime Achievement Award; he sang a dark, almost taunting version of Masters of War that stunned and baffled the audience. But amidst the calamities of the day, he was telling me to find some old vinyl and listen to the Mississippi Sheiks. I was all ears.

Those liner notes set me on a course in American musicology that’s never ended. The Sheiks, it turned out, were a Black string band from the 1930s, founded by a fiddler who was once a slave. I loved their unique, early jug-band style of music, and realized that I’d been hearing their stuff for years; they were the originators of Sittin’ on Top of the World, one of the best known songs in the folk and country vein that was popularized early by the Grateful Dead and recorded by Dylan on his Good as I Been to You in 1992.

As I delved into these musicians of old, I realized that Dylan has been teaching us about American music since he recorded Song to Woody (“here’s to Cisco and Sonny and Leadbelly too”) on his first album, way back in 1962. His deep interest in American roots music became evident in 1972, when he played on the fabulous Doug Sahm and Friends with the New Orleans gris-gris man Dr. John (Mac Rebennack), the San Antonio organ player Augie Myers and many others. He’d hook with these musicians again and again, particularly Myers, who played on Dylan’s Time Out of Mind decades later.

The TOOM sessions also included on keyboards the legendary Memphis producer and raconteur Jim Dickinson. Although this was their first recorded collaboration, Dickinson and Dylan were already good friends, going way back to the early ’70s, when the late Dickinson (who appears briefly in the autobiographical Chronicles) won the bard’s respect by recording John Brown, perhaps Dylan’s most searing antiwar song. I spent a lot of time in Memphis from 2005 to 2008, and my experiences there taught me another great lesson about Dylan: the pains he takes to learn.

According to Dickinson, Dylan came to see him once at his Zebra Ranch, just south of Memphis, to talk through his experience with Daniel Lanois during the recording sessions for Oh Mercy in New Orleans. He really liked Memphis and knew all the bands, even the obscure ones. Around 1999, he recorded a video at the New Daisy Theater on Beale Street and invited a select group to listen in. One of them was Robert Gordon, the local music journalist and the author of It Came From Memphis, a deeply researched book on the city’s lively blues and rock scene. Dylan asked to meet Gordon; after shaking hands, the writer says, the famous songwriter told him: “your book’s a classic, man.” That’s how much he knew the music.

But he also understood the history of Memphis as a crossroads, the place where Black and white musicians came together even during the darkest days of segregation to create the culture that became rock & roll. He explains that riddle in the haunting Mother of Muses on Rough and Rowdy Ways, his last CD, when he sings the praises of Zhukov and Patton, the Soviet and American generals most responsible for defeating fascism, who cleared the path for Presley to sing/Who carved the path for Martin Luther King. It was a profound thought, and again I was reminded of Dylan’s deep knowledge of my country, from the Civil War to today.

That knowledge, of course, has been part of his public persona since 2006, when Dylan displayed his intricate knowledge of America with his Theme Time Radio Hour, every minute of which was a virtual encyclopediaof our musical heritage. His truth-telling is even more evident a few songs later on RARW, which he closes with his 17-minute elegy, Murder Most Foul. With great emotion, Dylan presents JFK’s murder and its meaning as breaking news, almost exactly as I remember it from 1963. Then, with the help of Wolfman Jack, the great DJ in the sky, he winds up his tribute by ticking off the names of dozens of musicians and artists who influenced him, and all of us, along the way.

At age 80, we must now add Dylan to that list, so he stands before us as a living link to all the greats who came before. Our troubadour, it turns out, was our teacher all along. Bob Dylan, Presente!

Tim Shorrock is a Washington-based writer and guitar player who grew up in Japan and South Korea during the Cold War.