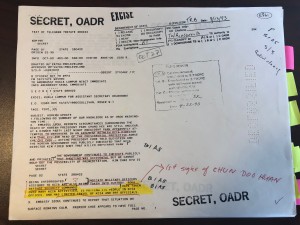

Three years ago, I released a tranche of select U.S. documents from the October 26, 1979, assassination of Park Chung Hee. Several of them have never been made public before, while others were previously released in the U.S. and South Korean press in my 1996 stories about the hidden American role in the suppression of the Kwangju Uprising in 1980. They include five key sets of diplomatic cables from October and November 1979 (click each link to read the PDFs in full):

— The secret cables from the US Embassy in Seoul reporting to Washington on the Park assassination and the immediate aftermath.

— US Embassy reports about the Pusan-Masan Uprising and the declaration of martial law.

— The newly declassified minutes of the first high-level meeting between US and South Korean officals after the assassination, along with the previously classified version that cut what Park’s successors said.

— Ambassador Gleysteen’s secret assessment of the Korean political situation one month after the assassination.

South Korean broadcaster MBC ran my story on the 10.26 documents on their national news show on October 27th, 2019. Watch it here.

PARK’S ASSASSINATION, THE US RESPONSE AND THE FIRST SIGNS OF CHUN DOO HWAN

A STORY IN DOCUMENTS

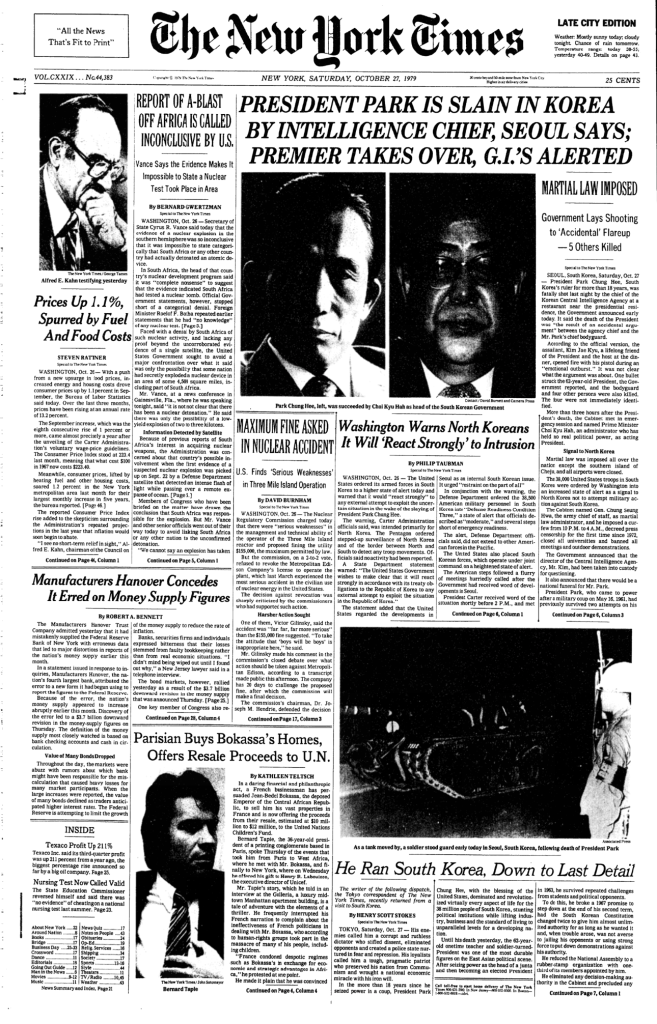

Just after midnight in Seoul on October 26, 1979, US Ambassador William Gleysteen received shocking news: President Park Chung Hee, the military dictator in power since 1961 and one of America’s closest allies in Asia, had just been shot to death by Kim Jae Kyu, the director of his own intelligence service, the dreaded KCIA.

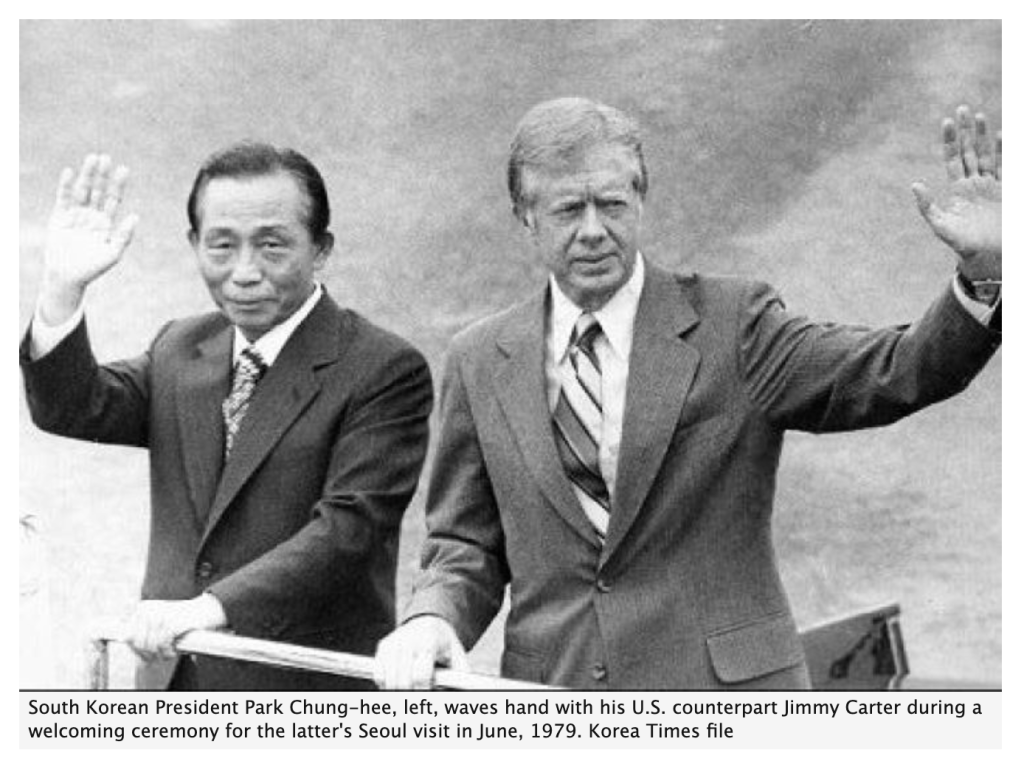

The event occurred only days after Park had sent Army Special Forces backed by tanks into the industrial cities of Pusan and Masan to quell South Korea’s largest street demonstrations since 1960, when nation-wide protests toppled the country’s first president, Syngman Rhee. Only a week earlier, Secretary of Defense Harold Brown had visited Park in Seoul to restore US-South Korean relations after a period of severe bilateral tensions, and promised to sell 36 F-16s to bolster his hand against North Korea.

The civilian uprising against Park in in Pusan and Masan (often referred to as “PuMa”) was marked this week by President Moon Jae-in in the second national commemoration of the event.“The Busan-Masan Democratic Protests were a great struggle that opened the dawn of democracy by overthrowing the Yushin dictatorship,” Moon said, describing the period as the “longest and harshest” dictatorship in Korean history.

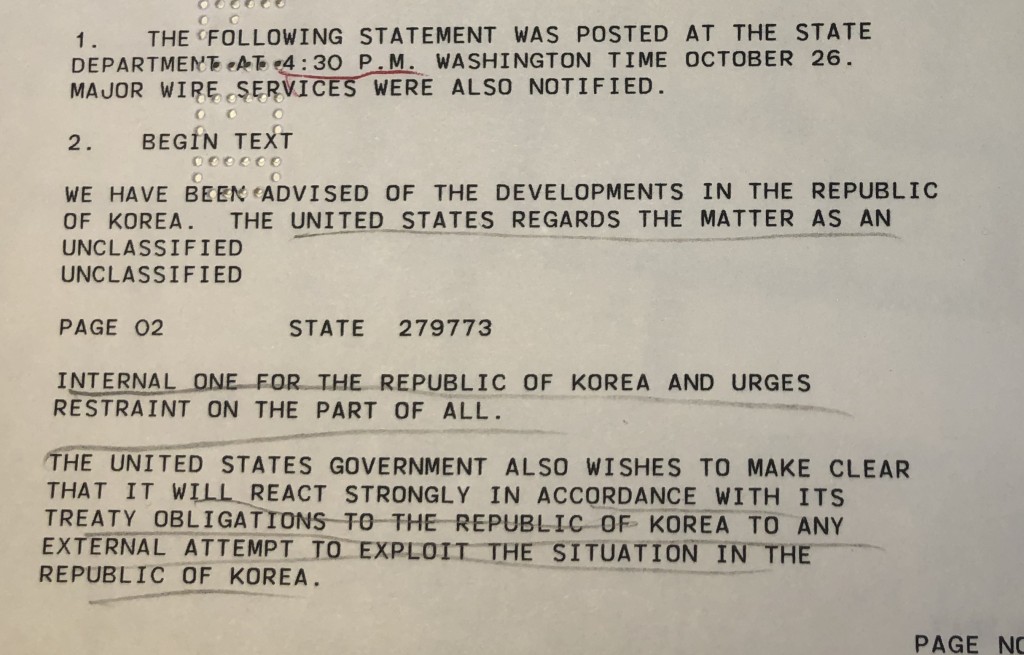

But despite the massive popular discontent about Park’s authoritarian rule, US officials at the time believed that relations between the two countries were back on track for the first time in years. As the news about Park filtered into Washington, the State Department issued a blunt warning to North Korea not to intervene. And to show Pyongyang he meant business, President Carter ordered the Pentagon to deploy the aircraft carrier Kitty Hawk to the peninsula and placed the 36,000 US soldiers in South Korea on high alert.

The United States Government…wishes to make clear that it will react strongly in accordance with its treaty obligations to the Republic of Korea to any external attempt to exploit the situation in the Republic of Korea.

In close consultation with US Forces Korea and its 36,000 US soldiers, the South Korean government extended martial law throughout the country except for the island of Jeju – the first time this had happened since 1972. “To avoid confusion, ROK has established direct links between martial law administrator [and] USFK public information officer,” Ambassador Gleysteen would report on October 27.

Thus began the most serious crisis in US- Korean relations since the Korean War.

It was a crisis that policy makers and the CIA never saw coming, and was quickly compounded a week later, on November 4, 1979, when militant students raided the US Embassy in Teheran (see the CIA’s rosy analysis from April 1979 of the “outlook for President Park” and the Washington Post‘s coverage of my findings from 2010).

Confronted with popular revolts against US allies on two continents, Carter’s national security team tried in Seoul what it could not do in Teheran: keep the lid on and “prevent another Iran,” as Richard Holbrooke, the assistant secretary of state for East Asia and the “apparatchik” of Korea policy, according to Gleysteen, would put it in a secret cable to the US Embassy in November 1979.

But the result was a debacle in which the United States ended up trying to maintain what it saw as the positive side of the Yushin system – political stability, US bases, rapid economic growth, a big market for US banks and oil and chemical giants – against the will of the Korean people.

President Carter’s ineffectual policies emphasized US national security interests over the democratic aspirations of the Korean population and helped pave the way for the rolling coup that allowed Chun Doo Hwan to seize control of the military, the KCIA and then the government itself.

That, in turn, led directly to the bloodshed in Kwangju in May 1980. Those events nearly destroyed the US military alliance with South Korea and, in my view, forever altered how Koreans view the United States. The seeds for that disaster were laid in the first days of the crisis, as the documents released today show.

KEY POINTS FROM THE CHEROKEE FILES:

- INITIAL REPORTS. The US Embassy, via Gleysteen, was apparently informed of Park’s death (described by the ambassador as “unspecified trouble”) around midnight on October 26, with confirmation coming two hours later. At around 8 AM on the 27th, Gleysteen met with Acting President Choi Kyu Ha and learned more details.

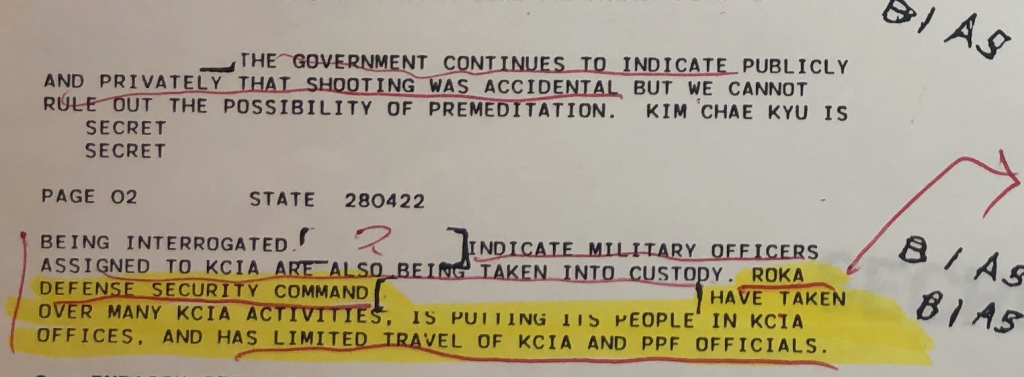

Last night, President Park apparently attempted to intervene in an argument between KCIA Director Kim Chae Kyu and heady of the Presidential Protective Force Cha Chi Choi…The government continues to indicate publicly and privately that shooting was accidental. But we cannot rule out the possibility of premeditation.

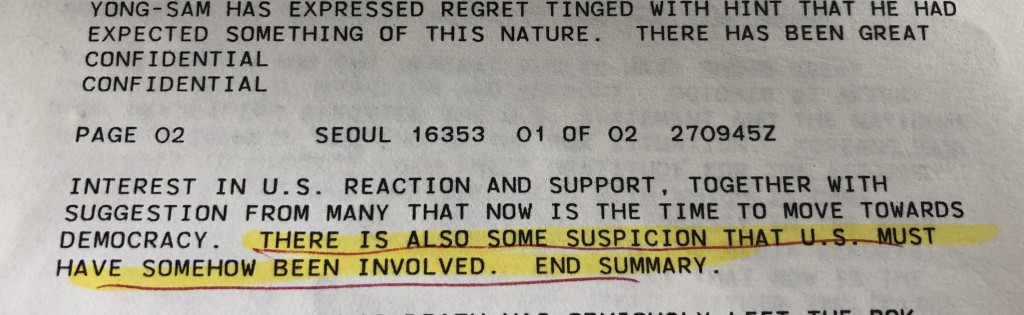

The first reports from the US Embassy in Seoul also include Gleysteen’s concerns that South Koreans believed that the United States may have been behind the assassination. “There has been great interest in US reaction and support, together with suggestion from many that now is the time to move towards democracy,” the ambassador wrote. “There is also some suspicion that US must have somehow been involved.”

The concern was real: KCIA Director Kim Jae Kyu had been very close to the the US CIA (Donald Gregg, the former CIA Station Chief in Seoul, told me in 1996 that he played golf regularly with Kim and that many US officials saw him as a moderating influence on Park). A month after the assassination, as I reported in my initial articles on my FOIA documents in 1996, Gleysteen persuaded a congressional committee not to hold hearings on the situation in South Korea because more reports about Kim Jae Kyu’s ties to the US embassy might be divulged.

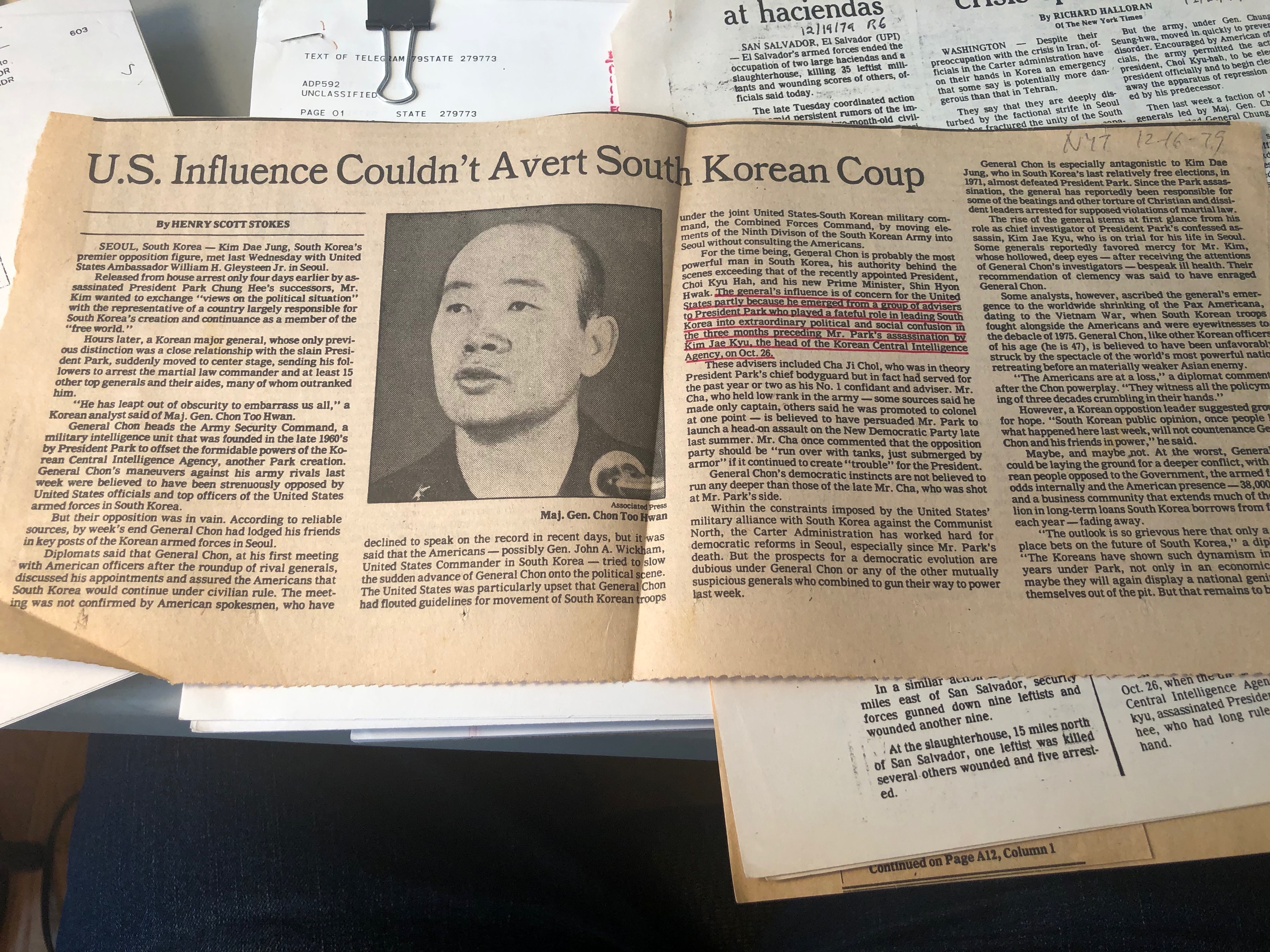

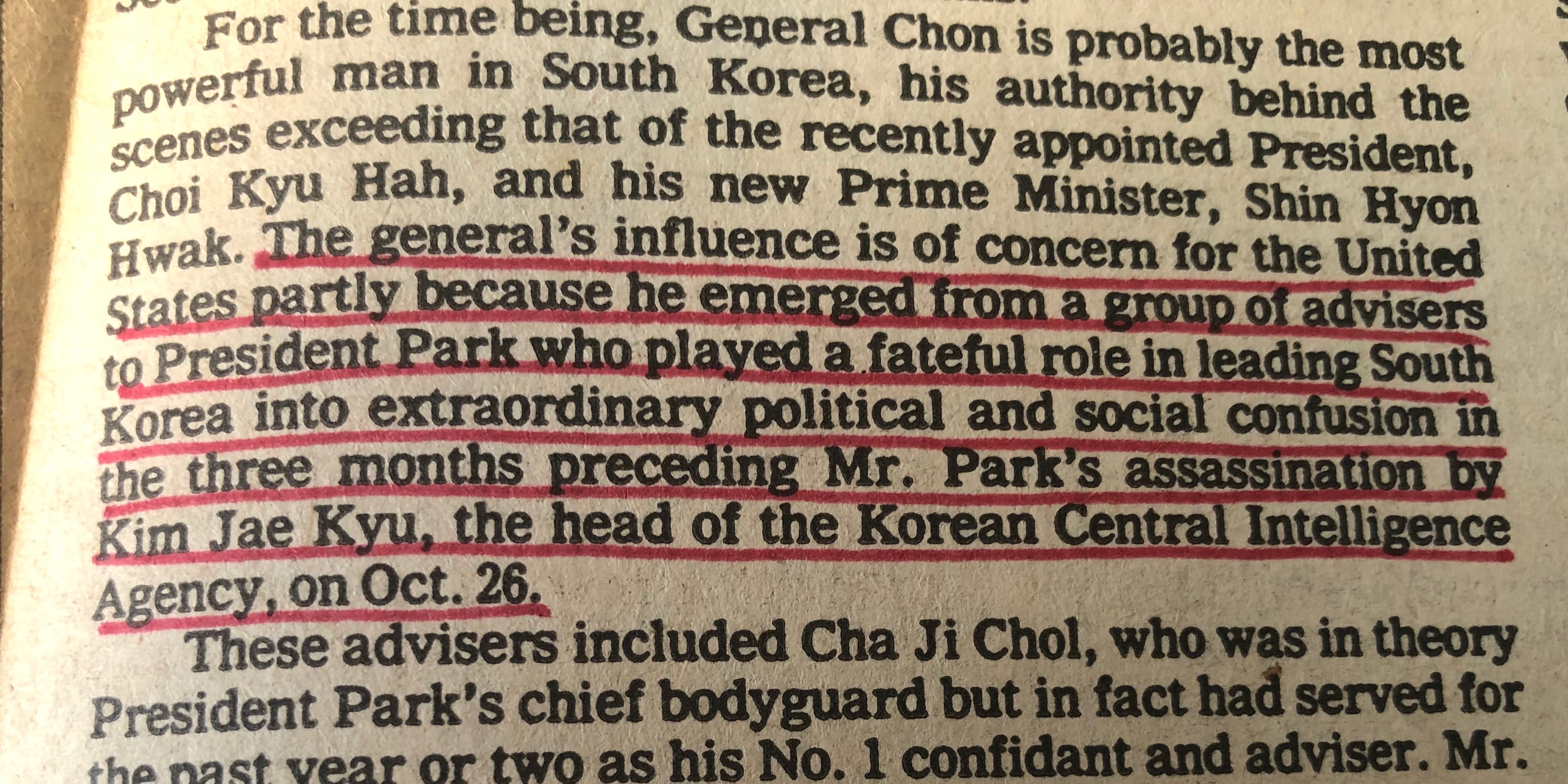

- FIRST SIGNS OF CHUN DOO HWAN. Gleysteen’s October 27 cable indicates that the US was aware early on that Chun Doo Hwan, then the commander of the Defense Security Command that was investigating Park’s death, was moving rapidly to take over South Korea’s security and military apparatus. The secret report, one day after the assassination, noted that the DSC was already assuming control of KCIA activities and keeping KCIA officials from traveling abroad (see the clips below from the Times about Chun’s December 12 coup within the military).

This information must have been supplied by the CIA, namely Bill Blakemore, the CIA Station Chief at the time who worked very closely with Ambassador Gleysteen (and, like Gregg, was quite close to Kim Jae Gyu). This document is important because it shows that the CIA knew from the earliest hours of this crisis that Chun and his group were consolidating power not only in the military but in the intelligence arena (Chun’s identity is apparently excised from the document. And for the record, most of the CIA documents I obtained about Kwangju are highly redacted – almost 90 percent in some cases).

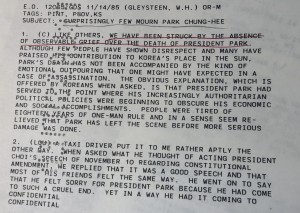

- “AN ABSENCE OF GRIEF.” Two weeks after the assassination, US officials seemed

shocked to learn that many Koreans were not unhappy at all about the end of Park’s dictatorship. “We have been struck by the absence of observable grief over the death of President Park,” Gleysteen wrote in a cable on November 14th. “Park’s death has not been accompanied by the kind of emotional outpouring that one might have expected in a case of assassination.” He quotes a taxi driver saying that while he “felt sorry” that Park had come to such a “cruel end,” he “in a way…had it coming to him because he was “too much of a dictator for too long.” Gleysteen and his CIA should have been listening to people like that all along instead of the bureaucrats, generals, KCIA officers, businessmen and other representatives of South Korea’s ruling class they depended on for their information about South Korea.

shocked to learn that many Koreans were not unhappy at all about the end of Park’s dictatorship. “We have been struck by the absence of observable grief over the death of President Park,” Gleysteen wrote in a cable on November 14th. “Park’s death has not been accompanied by the kind of emotional outpouring that one might have expected in a case of assassination.” He quotes a taxi driver saying that while he “felt sorry” that Park had come to such a “cruel end,” he “in a way…had it coming to him because he was “too much of a dictator for too long.” Gleysteen and his CIA should have been listening to people like that all along instead of the bureaucrats, generals, KCIA officers, businessmen and other representatives of South Korea’s ruling class they depended on for their information about South Korea.

In a 2010 article, I wrote this about the CIA report mentioned above:

Months before the assassination, the CIA dismissed the worker and student resistance [in 1979], as well as the political opposition, as unorganized and ineffectual and unable to muster public sympathy for its demands for greater democracy and worker rights. Park, the CIA reported, “seems fully capable of retaining his firm grip on power into the 1980s.”

But it warned that an economic downturn or political over-reaction could drive the opposition to “coalesce, and [Park] might not have a sufficiently deep reservoir of support to maintain his political position.” Still, chances for that were small, the agency said, because South Korea’s “active dissenters” numbered from “the hundreds to perhaps a few thousand,” in a country of 37 million. Moreover, “the average Korean wage earner” saw student protest as a “reflection of immaturity and lack of ‘real responsibilities,’” and was unlikely to participate in dissident politics.

As I concluded, “this analysis turned out to be a colossal mistake.”

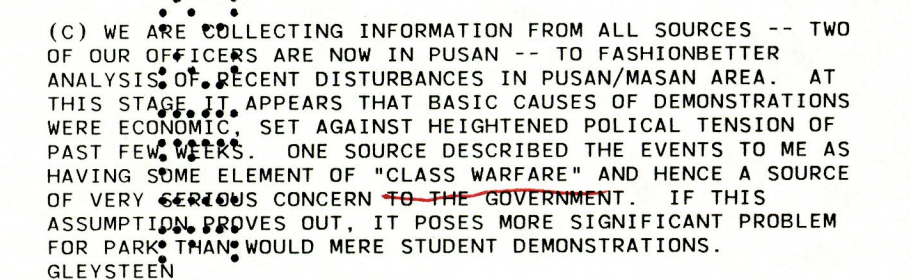

- THE STUDENT AND WORKER UPRISING IN PUSAN AND MASAN SHOCKED THE EMBASSY. Because of the US mindset towards Korea that industrial workers had no interest in mass protest, the presence of thousands of workers (many from the Masan Industrial Zone) in the streets of Pusan was disconcerting to US officials. “One source described the events to me as having some element of ‘class warfare’ hence a source of very serious concern to the government,” Gleysteen wrote in an October 25 cable. “If this assumption proves out, it poses more significant problem for Park that would mere student demonstrations.”

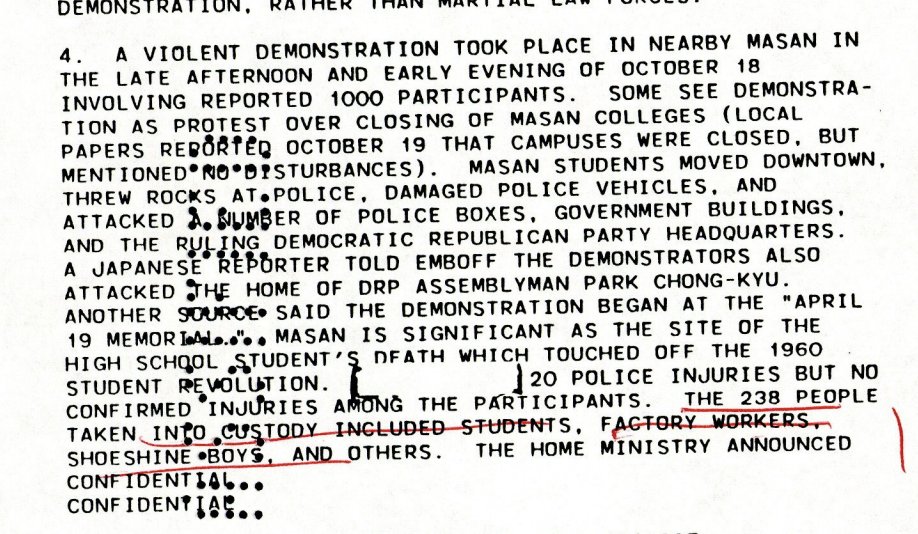

Earlier, in a cable on October 19, Gleysteen described the seriousness of the protests in Pusan and Masan (see the attached New York Times report from the scene for details), which led Park to deploy Special Forces to the city (the same units that were later deployed by Chun to Kwangju). The US Embassy had precise figures on the number of people involved and detailed information about arrests made by Park’s security forces, which may explain why this cable includes a cautionary note: “This message appears to contain sensitive intelligence information.”

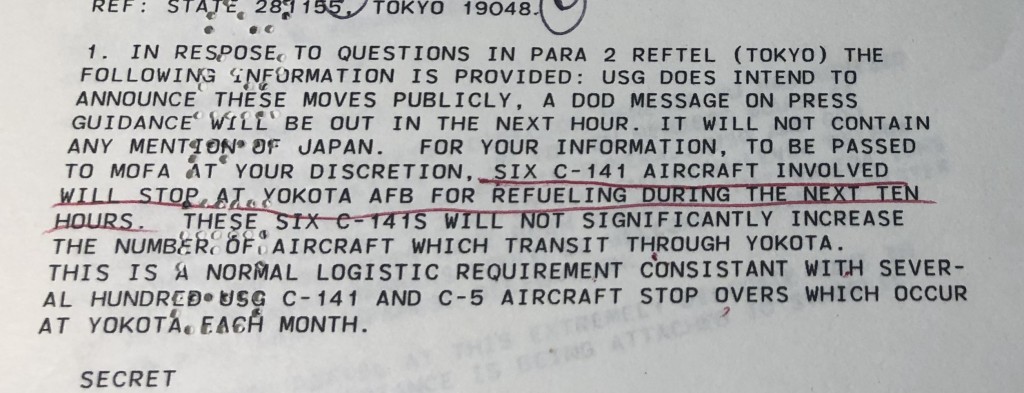

- US MILITARY DEPLOYMENT THROUGH JAPAN – SECRETLY. A US embassy cable about the emergency movements of US forces into South Korea underscores the sensitivities of Japan’s ties with Seoul 40 years before they broke down in 2019 over the 1965 Normalization Treaty. The cable, dated October 28, states that the US military, in its deployment of assets to the ROK in the immediate aftermath of the Park assassination, was sending six C-141 transport aircraft to Korea through Yokota AB in Japan (the headquarters of the UN Command-Rear). In its public statements about the deployment, however, US officials kept that information out. “A DOD message on press guidance will be” published soon but “will not contain any mention of Japan,” it stated, leaving that decision up to Tokyo.

- US DIPLOMATS PLEDGE TO SUPPORT “MODERATION” AND PREVENT THE “THREE EVILS.” One cable dated November 3, 1979, provides the minutes of the first high level diplomatic meetings between the US and the ROK after Park’s death, including verbatim comments made to US Secretary of State Cyrus Vance (and other high-ranking officials) from the ROK Foreign Minister, Park Tong Jin, as well as President Choi Kyu Ha.

When I first obtained this cable in 1996, it was highly redacted, with all the comments from the Korean side completely blacked out. I got some documents further declassified a few years ago, with all of Park’s and Choi’s comments restored. The conversation with Park set the stage for US policy making – trying to find a “middle ground” between the conservative military and the militant opposition (the unclassified version of this has never been released or published).

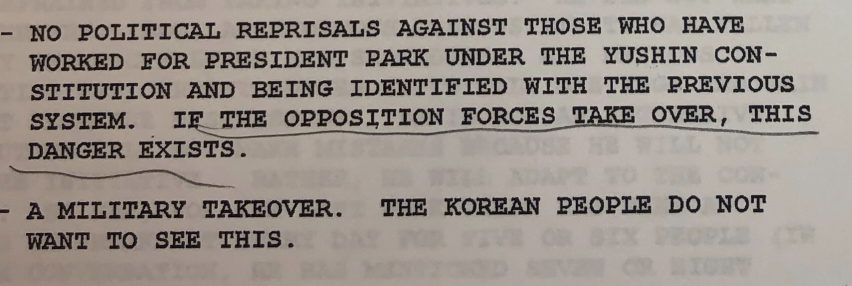

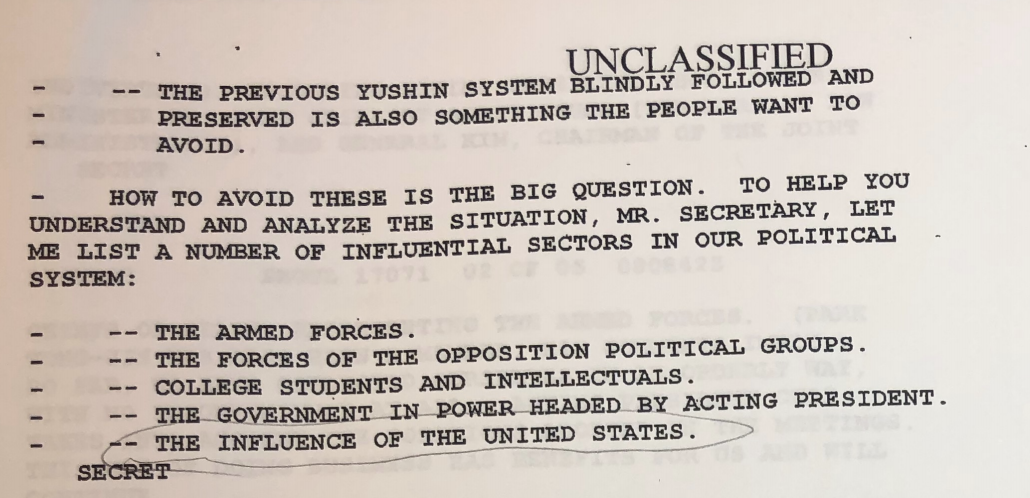

The once-secret transcript shows how deeply South Korea’s ruling circles around Park feared the opposition. In the meeting with Vance, which included Richard Holbrooke, Foreign Minister Park explains that the “Korean people” are primarily concerned “about the maintenance of stability.” Specifically, he said, they “see that that there are three evils to be avoided.”

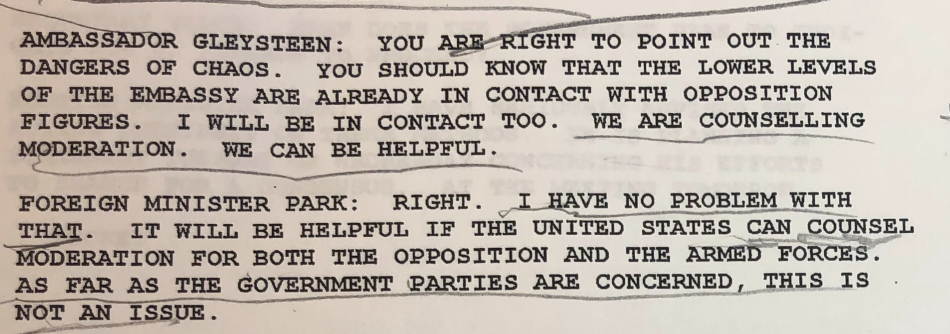

Park later clarifies that the “three evils” mean “political reprisals, military takeover, and the indefinite continuation of Yushin. In my view, blind prolongation of Yushin in hopeless.” But unfortunately, he adds, “the opposition forces believe that there is now a new era, and that they will be able to take over the government.” Gleysteen, speaking for the US government, responds that he will cooperate with that effort and counsel “moderation” with the opposition. Vance adds: “We will be careful to counsel moderation.” Park is obviously gratified by the support.

This conversation sets the stage for the US attempt over the next few months to steer the opposition away from what Gleysteen considered to be “extreme” demands from the opposition for an immediate return to democracy.

- GLEYSTEEN “DISCOURAGED.” A month after the assassination, in the last set of cables in this set, Ambassador Gleysteen admits to enormous US influence but cautions that the “extreme wing of the dissident/opposition” is making it difficult to find a “third way” of moderation.

The rest is history.