How Ralph Nader Sold Me Out to the Reagan McCarthyites: A Lesson in Cold War Cowardice

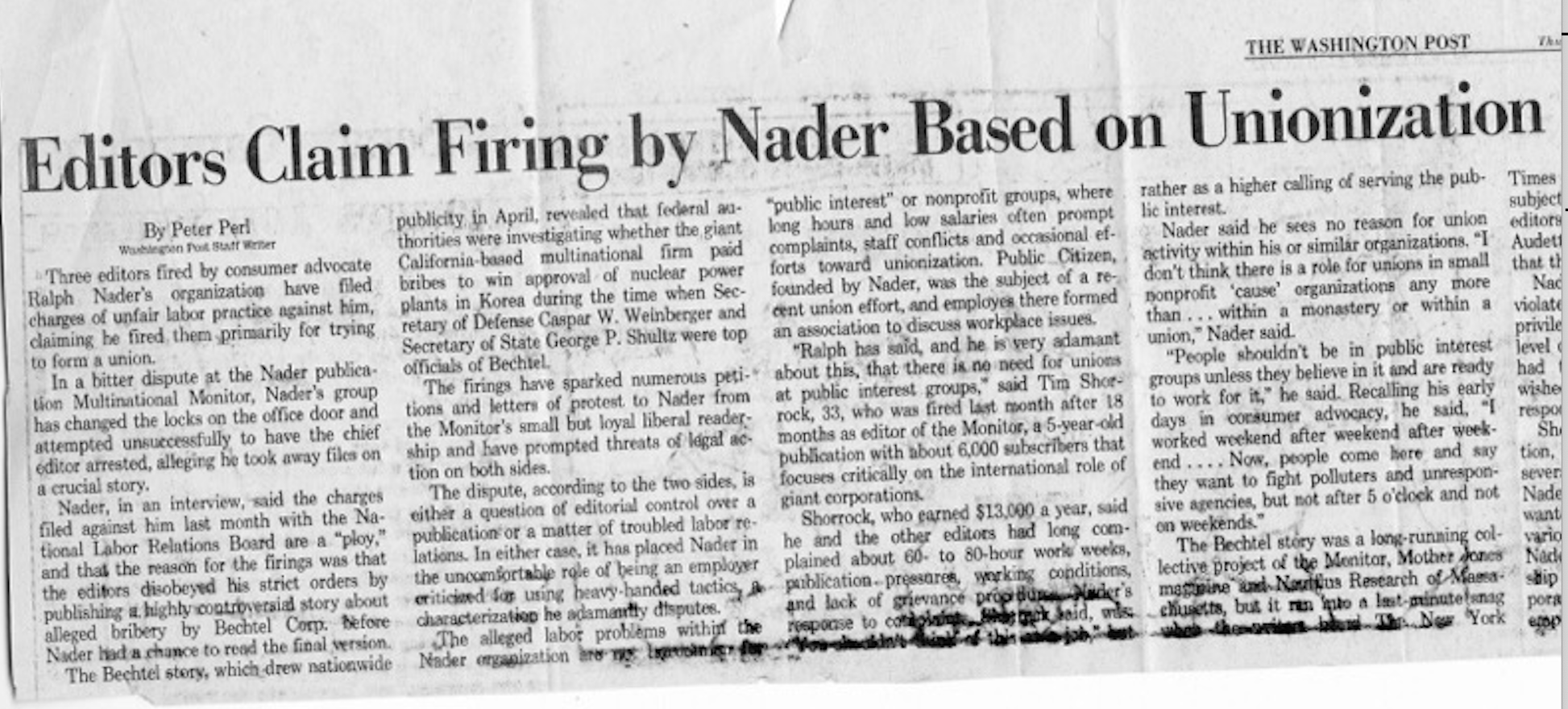

In 1983, only a few months after I arrived in DC from San Francisco, I came under attack from a silly right-winger named Cliff Kincaid. This experience took place when I was just 32 years old, and completely green to the vicious politics of Washington. At the time I was the editor of Multinational Monitor, a magazine owned and controlled by Ralph Nader, who at the time was still a liberal centrist, trembling in fear at the power of the right and the popularity of Ronald Reagan. My encounter with Kincaid was frightening; but worse still was Nader’s cowardly response. Indeed, that experience more than any other led me to part ways with Nader, who has of course emerged since then as a great (if very late) champion of progressive and leftist causes. He fired me in 1984 over deep political differences, and this incident should tell you why (and he went absolutely nuts when the Washington Post reported on his union-busting). Back in the early 1980s, except for courageous leftists like Noam Chomsky, it was hard to find people willing to stand up to right-wing zealots. As Phil Ochs once sang, derisively, of Nader-type political activists, “Love me, love me, love me, I’m a liberal.”

How Ralph Nader Capitulated to the Right

By Tim Shorrock

My first run-in with Nader took place just a few weeks after I started my job. It involved three players in Washington’s crazy-quilt political culture — the Institute of Policy Studies and Counterspy Magazine on the left, and the weekly newspaper Human Events on the right. The incident set the stage for nearly everything that followed in the brief relationship between Nader and me (for the full story, see my posting on this site, Michael Moore on “Here Comes Trouble,” the Left, the Wall Street protests – and Ralph Nader.

In January, 1983, I obtained copies of a confidential World Bank document concluding there were serious safety problems with the nuclear power program in South Korea, one of the most ambitious in the world up to that point (and a huge, multi-billion dollar market for the U.S. multinationals Bechtel and Westinghouse, which capitalized on U.S. pressure to beat out their foreign rivals for the contracts). I saw the document as a chance to kill two birds with one stone: draw some press for the magazine and get my tenure as editor off to a good start. So, after getting approval from Nader, I released the document in a press conference with the editors of Counterspy, a local magazine that investigated the CIA.

The event was a success: the story made UPI and the front page of two major papers in Seoul, where the press at that time was under heavy censorship. After initially denying the report, the Korean government said it would appoint a committee to study nuclear safety. I felt pretty good.

But a day or two after the press conference, Cliff Kincaid, a reporter with Human Events and probably the most notorious red-baiter in Washington barged into my office, demanding to know why I had sat in the same room as the editor of Counterspy, the “murderers of Richard Welch” (Kincaid claimed that in the 1970s, Counterspy had caused the assassination of the CIA station chief in Athens by publishing his name; the charge — repeated frequently by the right — was completely false, but Counterspy never lived it down).

I have a deep aversion to right-wing, neo-Nazi types, and a quick temper to boot. And, being new to Washington at the time, I had no idea that Human Events was so well read (Reagan supposedly devoured it with his cereal every morning). So instead of kicking Kincaid the hell out of there, I decided to confront him and defend Counterspy, Multinational Monitor, and my right to say and write anything I damn well chose.

“You’re full of shit,” I told Kincaid.

“Counterspy wants to abolish the CIA. Do you?” Kincaid shot back.

“Of course.”

“Will you say that on tape?”

“I have nothing to hide.”

And I proceeded to engage Kincaid in a debate on Cuba, the CIA, and God knows what else in front of a tape recorder. What I remember most about that interview (really, an interrogation) was Kincaid screaming at me, over and over again in his shrill voice: “Are you a socialist? Are you a socialist?” And me saying that, even if I was, he wouldn’t have the vaguest idea of what I was talking about.

Later that afternoon, one of Nader’s aides called me. Kincaid had called for Nader’s response to my comments, and by the tone of the aides’s voice, I could tell this was Serious Business. I explained that I had said nothing that could embarrass Nader (he was out of town) but admitted that I was stupid to have talked to Kincaid. Still, the aide was worried.

“Ralph’s never been red baited before,” he said. “The business press might pick this up and really hurt him.”

Kincaid’s story, “Nader Establishes Close Links with IPS,” ran on February 19, 1983. It turned out to be a typical Human Events-style attack on IPS, full of innuendo and guilt by association.

“In a move that could seriously undermine their image as protectors of the ‘public interest,’ Ralph Nader and his raiders have recently been observed making alliances with the extreme left,” the lead read. On January 31, Kincaid reported, Nader held a joint news conference with the Government Accountability Project of IPS “to attack President Reagan.” He described IPS as “a collection of radicals, Socialists and Marxists” that “has played a key role over the years in apologizing for Communist movements and governments and working to restrict the operations of U.S. corporations and intelligence agencies.”

Kincaid combined that information with the news that the Monitor and Counterspy (“the notorious anti American magazine”) were working together to prove that Nader was indeed in bed with the “far left.” To drive his point home, he quoted from a stack of Monitor issues I had given him, all published before I had started working there.

The January, 1983, issue–the last one before I took over–had “attacked Jeane Kirkpatrick…and the Heritage Foundation for criticizing U.N. attempts to implement” restraints on multinationals.

Then came the clincher:

“Shorrock,” Kincaid wrote, “indicated that he was a Socialist who favors ‘public decisions about major economic policies.'” Radical stuff. But there was more: “Shorrock also said that socialism involves ‘deciding that we don’t want to have our CIA train the Korean CIA to unleash its violence against Korean worker groups to keep their wages low so American multinationals and Japanese multinationals can come in and exploit Korean workers.” (whoa, call the red squad). Not only that, I had defended Counterspy, called for the abolition of the CIA, believed that “the KGB is not a threat,” and supported “a lot of what the Cuban government does.”

As far as I was concerned, none of these quotes were damaging, some were laughable, and most had been taken out of context. So I was more than shocked a week later when the next issue of Human Events came out with another headline story: “Nader Disavows Views of His Editor.”

Without even informing me, Nader had instructed his aides to call Human Events with the following statement: “Ralph Nader does not approve of the views expressed by Tim Shorrock, the editor of Multinational Monitor, as reported in Human Events, Feb. 19, 1983.” Nader told the newspaper that the Monitor was “an independent publication over which Nader holds no control.” That was an outright lie: Nader hired the staff, personally signed our checks and read each issue before it went to press. Worse, not once had Nader checked with me as to the accuracy of Kincaid’s quotes; nor had he indicated which statements of mine he disagreed with. And apparently he saw no reason to defend himself or his colleagues at IPS, which his close friend Marcus Raskin had founded.

I was blown away. Was Ralph Nader afraid of a shrill right-wing newspaper? Was this all I could expect when the Monitor, his own magazine, was under attack? Had he really refused to defend his own editor? Furious to the point of quitting, I demanded a meeting with Nader to clarify the situation. But Nader didn’t want to talk.

“Go back to work and forget about it,” he said.

In 1984, long after I had been fired, I finally realized how gutless and craven Nader had been during this episode from an article by journalist Pat Aufderheide in the September/October, 1984, issue of the Colombia Journalism Review. In her piece, which was entitled “Nader’s Unhappy Raiders” and accompanied by a snapshot of me posing with a notebook in front of the San Francisco Bay Bridge, Nader told Aufderheide that he had been angered by the Human Events incident because I had characterized the Monitor “as socialist, which limits its readership and also is not true.”

Nader, it seems, had not even bothered to read Kincaid’s article in Human Events. Not exactly a profile in courage, if you ask me. Instead, it’s a telling moment in the Cold War, when standing up to the far-right really took guts.

Endnote: At the time, the only leftist who wrote about my dispute with Nader was the great Doug Henwood, editor of the now-defunct Left Labor Observer. I’m forever grateful to him for giving me a voice during those dark times. His story was balanced but tough. He also printed my summary of Nader, where I didn’t mince words. I still think this holds up.

“Ralph Nader may look like a democrat, smell like a populist, and sound like a socialist – but deep down he’s a frightened, petit bourgeois moralizer without a political compass, more concerned with his image than the movement he claims to lead: in short, an opportunist, a liberal hack. And a scab.”