Part One: Japan, Democracy, and the Globalization of Nuclear Power (Updated throughout 3/20/2011)

Part Two: Nuclear Gypsies (posted 3/20/2011)

Since I woke up last Friday, I’ve been monitoring the terrible earthquake and tsunami that hit Japan and watching with horror as the Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s nuclear complex in Fukushima transformed a natural catastrophe into an environmental crisis of the first order. It’s been a painful experience because I grew up in Tokyo, have a Japanese step-mother, and have many friends, both American and Japanese, living there.

The unfolding nuclear disaster has also triggered memories of the times I spent in Japan as a journalist in the 1980s, when I wrote for and worked closely with a Japanese citizen’s group called Pacific Asia Resource Center (PARC), which was organized in the 1960s by Japanese antiwar, environmental and labor activists and became a regional center that build close ties with people’s movements throughout Asia. One of the activists I met during that time was the late Dr. Jinzaburo Takagi, who went to co-found the Citizens’ Nuclear Information Center (CNIC), Japan’s most prominent opponent of nuclear energy and an important source of news and information about the current crisis at Fukushima (click here for CNIC’s statement on the crisis).

Because of that experience, I was quite familiar with TEPCO, the world’s third-largest utility, and its long history of falsifying records and playing down the dangers of atomic power and radiation. Partly out of that knowledge, I posted my story, “TEPCO’s Shady History,” on March 14.

But, as my friends and family know, I’m a pack rat, and my apartment in Northwest Washington, D.C, is filled with dozens of boxes of files from my years as an Asian-focused journalist. It turns out that many of my first articles were about nuclear power and U.S. nuclear exports to the region. This week I’ve been digging threw my archives and have found some timely – and disturbing – reports from myself and others on the nuclear industry, its labor force (many of whom were low-wage subcontractors called “nuclear gypsies” who did the most dangerous tasks), and how the industry subverted both the environment and Japan’s democracy.

Many of these articles were published in AMPO, PARC’S news and research quarterly, and other movement publications (“AMPO” is short for the U.S.-Japanese Security Treaty, which was a prime target of the Japanese antiwar movement for much of the 1960s and 1970s). I want to share some excerpts of this work to shed light on the history of nuclear power in Japan and on TEPCO’s Fukushima plant itself. I’ve scanned many of these articles so you can read them in full for yourself.

I begin this primer with an article I co-authored with Peter Hayes, an Australian writer and activist who for many years has directed the Nautilus Institute, a think-tank that focuses on Northeast Asian energy and political issues (Peter has been interviewed extensively in the media about the Japan disaster, as you can see on the website). Our AMPO article (PDF) was mostly about South Korea, which has a massive nuclear power industry as well as a robust anti-nuclear movement. But we went back and traced how the nuclear industry spread globally, first in Europe and then in Asia:

Dumping Reactors in Asia. AMPO/1982

The nuclear industry was born a deformed monster in Japan when the U.S. warplane Enola Gay dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Afterwards, the U.S. attempted to monopolize nuclear technology, until the Soviet Union exploded the dream in 1949. In December 1955, U.S. President Eisenhower announced a second birth in the nuclear family, the “Atoms for Peace” program. It was designed from the start as a global industry whose technology would be provided by U.S. companies. By 1956, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and the U.S. Export-Import Bank (Eximbank) had agreed to assist two dozen countries which entered “Agreement for Cooperation” with cheap, subsidized money, enriched uranium and technical assistance worth (at the time) $250 million.

But this commercial “kid brother” of the nuclear bomb grew slowly. While the military spawned dozens of nuclear-powered submarines – a lucrative market for nuclear vendors like Westinghouse – the first flush of nuclear enthusiasm procuded mostly small research reactor sales in the United States. Power reactor sites in the U.S. were stalled during the late 1950s by the debate over private-versus-public atomic power. It was the European stampede for nuclear power known as “Eurotom” (or European Atomic Energy Community, founded in 1957) that provided the first great opportunity for U.S. nuclear vendors – an opportunity precluded at home by political forces and economic constraints. This story was repeated in Asia in the 1970s.

From their European springboard, the U.S. light water reactor manufacturers plunged aggressively into the U.S. market, beginning with the Oyster Creek General Electric plant in 1963 (Note: it remains the oldest operating nuclear power plant in the U.S., and shares the same design share as the reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi complex). This project was quickly followed up by eight more “loss leader” plants where vendors charged buyers less than cost to establish a market. From the turnkey market, the industry leapt to the “bandwagon” market, with U.S. utilities jostling to place 104 orders between 1966 and 197o. After 1962, the U.S. industry moved quickly to adopt partners overseas. In Japan, GE licenced Toshiba (which built the Fukushima reactors using GE technology) and Hitachi. In France, Westinghouse licensed Framatone…

Then it happened: the Bandwagon crashed into a wall of anti-nucleaer action, safety regulations, escalating cost, declining electricity demand, utility generating over-capacity and technological failure – all culminating in Three Mile Island in 1979…A wave of order cancellations and deferrals hit the industry in the stomach.

Since then, the U.S. industry has never been the same – and has looked overseas, in countries like Japan, South Korea and now China, for its sales. In a sign of the times, Westinghouse, once the biggest name in the nuclear industry, was sold in 2006 to Japan’s Toshiba, the maker of the Fukushima reactors.

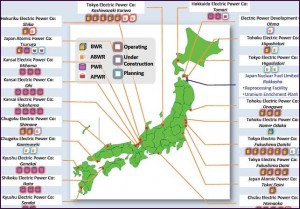

The current state of the Japanese nuclear industry. Japan’s first commercial reactor began operating in 1966, and nuclear energy has been a national priority since 1973. Currently, the country’s 55 reactors provide some 30 percent of Japan’s electricity. That figure is expected to increase to at least 40 percent by 2017, according to the World Nuclear Association, an industry group (the source of the graphic to the left – click here for a CNIC map of all nuclear power projects in Asia).

But as the proverbial song goes, “there’s a hole in the bucket, dear Henry, dear Henry, there’s a hole in the bucket, dear Henry, a hole.” In fact, there’s several big holes: I’m speaking of the industry’s and government’s tendency to play up the positives of nuclear power and ignore its many downsides; the undemocratic nature of the siting and building process, which has historically excluded citizens’ groups and made it very hard to oppose – let alone block – the construction of new plants; and the two-tiered labor system, which has created an underclass of contract workers – “nuclear gypsies” – who do the dirty work at the plants and suffer the most from radiation and other industrial diseases.

I first became aware of the seriousness of these issues in 1981. During one of my visits to Japan, the media was filled with stories about a major radioactive spill at the Tsuruga Nuclear Power Plant in Fukui Prefecture. As recounted in History.com:

Tsuruga lies near Wakasa Bay on the west coast of Japan. Approximately 60,000 people lived in the area surrounding the atomic power plant. On March 9, a worker forgot to shut a critical valve, causing a radioactive sludge tank to overflow. Fifty-six workers were sent in to mop up the radioactive sludge before the leak could escape the disposal building, but the plan was not successful and 16 tons of waste spilled into Wakasa Bay.

Despite the obvious risk to people eating contaminated fish caught in the bay, Japan’s Atomic Power Commission made no public mention of the accident or spill. The public was told nothing of the accident until more than a month later, when a newspaper caught wind of and reported the story. By then, seaweed in the area was found to have radioactive levels 10 times greater than normal. Cobalt-60 levels were 5,000 times higher than previous highs recorded in the area.

Finally, on April 21, the Atomic Power Commission publicly admitted the nuclear accident but denied that anyone had been exposed to dangerous levels of radiation. Two days later, the company running the plant declared that they had not announced the accident right away because of Japanese emotionalism toward anything nuclear. The public also learned for the first time that, in an earlier incident at the same plant in January 1981, 45 workers had been exposed to radiation.

RESOURCE: Chronology of 1981 Tsuruga Accident from the Japanese press (10 page PDF).

Among the injured workers at Tsuruga were many subcontractors. According to the Japan Times (this article is included in the chronology PDF above):

[The government] said 48 company subcontractors joined in the removal operation…exposing themselves to [radiation]…The staffers and subcontractors were reported to have tried to dispose of the leaked waste water using buckets and wiping the floor with cloths thereby exposing themselves to radioactivity.

According to a later report carried by UPI, quoting Japan’s Natural Resources and Energy Agency, “the radiation levels were 7,600 to 11,000 times higher than normal readings.” The spill led the Japan Times to declare in an editorial:

What happened at Japan Atomic Power Company’s Tsuruga plant is more than a crime than an accident…There is little doubt that the leak of radioactivity there was caused by a faulty design of facilities and operational errors and the resulting damage magnified by the company’s willful attempt to hide all this…

The plant’s operator did not inform the government of these accidents. Nor did it notify the inspectors stationed there. No entries were made in the log, it is said, concerning the leaks. In other words, the company as well as the plant management tried to “cover up” the whole thing.

Sadly, this experience has been repeated dozens of times over the past 30 years.

“No Nukes Move Carried by Working Class” — RODO JOHO/1981

The lack of democracy in the hearing process was detailed in RODO JOHO, a newsletter published in the 1980s by a network of militant trade unions (and very similar in style and politics to Labor Notes in the United States). Part of its organizing included mobilizing against, and educating about, the public hearing system because it has historically been so undemocratic:

When a nuclear power plant is to be built, a “public” hearing is usually held as formality to gain local residents’ approval and tell them how safe they are. But the “public” hearings are that in name only. Opposition groups boycott these hearings because they are rigged to ensure the construction of the plants.

When many of Japan’s reactors were in the planning stage, RODO JOHO and other groups mobilized thousands of local workers and citizens to protest the lack of transparency at these hearings.

In December 1980, for example, more than 8,000 people, mainly from labor unions, joined local residents at Kashiwazaki in Niigata Prefecture (another TEPCO-owned facility and the largest generating plant in the world) gathered to protest against this hearing. Over the next few months, the activists built “Solidarity Huts” near the site and continued their campaign to stop expansion of the plant. Then, in February 1981, TEPCO obtained a court injunction to remove the huts and hired workers to forcibly remove them as about 1,000 riot police stood guard. Here’s how the incident was reported by the Japan Times (PDF):

In a predawn surprise operation, Tokyo Electric Power Co. removed two structure local residents had been using as fortresses in a campaign against the construction of a nuclear power plant the company is promoting. The operation was conducted as about 1,000 riot police stood guard in drizzle, but no major trouble occured…Taking notice of the movement, some 400 opponents assembled at the two structures called “Solidarity Hut” and “Beach Teahouse” they had built…They sat inside in an attempt to prevent the removal of the structures….The plant eventually will have seven reactors…An official of [TEPCO] in charge of the plant said he was relieved that the huts had been removed.

In 2007, an earthquake in Niigata triggered a serious accident at Kashiwazaki that was covered up by TEPCO, resulting in a government investigation into the company.

In February 1981 6,000 people participated in opposing the Shimane “public” hearing (in western Japan). During the hearing, according to a report by the Kyodo News Service,

About 50 opponents, including union leaders, demanded to [the chairman of the prefectural committee] that petitioners be allowed to explain their appeals and that spectators be allowed to witness committee debates. As [the chairman] refused to give in to the opponents’ demands, the opponents surrounded him and blocked him from entering the meeting room. The president of the prefectural assembly called police about 11:30 AM to disperse the demonstrators. In skirmishes with the demonstrators, police arrested two who entered the room, on charges of tresspassing…A prefectural organization of labor unions filed a protest with Matsue police, claiming that the two arrests were made illegally.

In March 1981, about 7,000 demonstrated against a hearing for a plant in Hamaoka. Their protest focused on construction of a nuclear power plant near a zone that scientists believe could be the epicenter of a future earthquake. This action received heavy coverage in the Japanese media, including this story from the Japan Times, via Kyodo News Service (PDF):

A total of some 7,000 protesters, consisting of labor union members, students and area residents, encircled the Hamaoka Town Hall and staged an all-night demonstration rally and sit-in…in an attempt to block the holding of the hearing sponsored by the Nuclear Safety Commission.

The construction of the No. 3 nuclear reactor…has arounsed stong opposition from areas residents concerned about its safety, since Shizuoka Prefecture is under the constant threat of the Tokai “Great Earthquake,” which seismologists predict may hit the area in the near future…

Demonstrators held an anti-nuclear power symposium at a nearby park, some 1 km away from the town hall…protesting the hearing, which they called undemocratic. They contended that a hearing held to present government opinion alone is not enough to ensure the safety of area residents.

Some 1,500 riot policemen were mobilized to check the activities of the opponents.

(Interestingly, the reactors used by Chubu Electric Power Co. were boiling water reactors designed by General Electric, which built the reactors at Fukushima. According to an April 9, 1981, account by Kyodo, Chubu claimed that the reactors “presented no problem, although the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission has reuled that a similar reactor belong to GE is defective…The NRC pointed out earlier that the cooling device in the GE’s reactor is defective.”)

Since the 1980s, the nuclear hearing process has improved, according to a 2010 article in Nuke Info Tokyo, CINC’s newsletter:

When agreement has been received for the construction plan itself, it is possible for the power company to move ahead with the nuclear-specific procedures in parallel with the environmental assessment process. The first step is the first public hearing. This hearing is legally required under a decision by the Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry (METI). METI hosts the meeting and the power company explains its construction plan. Residents are selected from amongst those who have submitted public comments to present their opinions about the plan. The power company responds to the residents’ comments, so in practice, it is not so much a hearing as an explanatory meeting. However, it provides formal grounds for claiming that the residents’ opinions were taken into considerations in the safety assessment.

Once a plant is granted a license, however, it becomes very difficult to stop the process:

Basically, there are not more opportunities for public involvement after a reactor establishment license has been awarded. However, in reality, if the project is not stopped before the environmental assessment begins, the process just keeps moving forward. A unique exception was when a plan to construct a reactor in Maki Town Niigata Prefecture (now Niigata City) was stopped by a local referendum after an application for a reactor establishment license had already been submitted. The license application was submitted on January 25, 1982, but the Tohoku Electric Power Company failed to acquire some of the land for the site, so the safety review was suspended. A local referendum was held on August 4, 1996, and 60.9% of eligible votes opposed the project. Even then, Tohoku Electric did not withdraw its plan until December 24, 2003.

CNIC therefore urges citizens’ to get involved immediately after a new contruction plan is announced:

If residents want to block a nuclear construction project, the earlier they do so the better. Effective ways of doing this include preventing the power company from acquiring land for the site, refusing to relenquish fishing rights and preventing the power company from obtaining agreement from the local authorities. As mentioned above, regardless of the lack of formal legal authority, no nuclear power plant will be built without the agreement of the local and prefectural governments. There are many examples of Japan where local communities have prevented construction of nuclear power plants in this way.

Still, in the early years of the industry, the unions and citizens’ groups were facing a buzzsaw: the combined forces of the Japanese government and the powerful nuclear industry.

“Japan’s Nuclear Energy Policies” — AMPO/1992

This article by Japanese researcher Fukumoto Takao provides a snapshot of how things stood in the nuclear industry in the early 1990s. It also provided a frightening preview into what has happened in Fukushima over the past couple of days with a look at the 1992 accident at the Kansai Electric Power Co.’s Mihama Nuclear Power Station Unit 2 in Fukui Prefecture, about 250 miles west of Tokyo – the first time an emergency cooling system had to be used in a Japanese plant. Takao began his story by describing how the nuclear lobby worked.

To promote nuclear power, the government and electric power lobby have always emphasized atomic energy’s positive elements to allay fears of radioactivity. These positive elements include: 1) the cost-effectiveness of nuclear power generation compared to other methods; 20 its alleged high degree of safety; and 3) because it doesn’t emit carbon dioxide it has a reputation as a clean energy source…Here a simple question arises. Those who say atomic energy is less harmful to the environment emphasize only the method of power generation. How can we ignore the problems of radioactivity, radioactive waste and accidents? Chernobyl showed what happens when an accident occurs at a nuclear power plant…

Takao then turned to the accident at the Mihama plant in Kansai, where a heat transfer tube in the steam generator ruptured, triggering the emergency core cooling sytem – the first time this had happened in Japan (according to the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation, which tracks such accidents, the Japanese government later reported that the accident “was caused by human error, some anti-vibration bars being wrongly installed by workers and sawn off short to make them fit.”) Takao continued:

This was a major accident, the kind which the government and power companies had assured the public could never occur…Even more serious is the fact that the accident occured not long after the reactor had undergone a regular inspection. The assurance the government and power companies had given us was based on the assumption that any trouble could be spotted through periodic inspections. The Mihama accident, however, proved that these inspections cannot be trusted. It offered dramatic evidence that a nuclear accident can occur anywhere and at any time.

The Chernobyl accident, which occured six years ago, graphically demonstrates the consequences of a nuclear accident. Chernobyl has taught us both how tragic and pervasive a nuclear mishap can be: such disasters do not recognize national borders…The contaminated area extends 950 kilometers east-west and 400 kilometers north-south. This would cover 70 percent to 80 percent of Honshu, Japan’s main island.

If such an accident were to occur in Japan, the scale of destruction and the number of evacuees would be 10 times greater than in the former Soviet Union. Radioactivity emitted from Chernobyl spread over Western Europe, and in this sense, nulcear power plants are potential destroyers of the global environment. Yet nuclear plants in Japan continue to operate…

Tragically, in 2004 the Kansai plant was against the scene of an accident that, until the latest disaster, was Japan’s worst nuclear accident. Four workers died and seven were severely injured when steam leaked from the reactor. The Japan Times reported at the time:

The 826,000-kilowatt reactor automatically shut down after the incident, officials at the nation’s second-largest utility said, adding they believe a lack of cooling water in the plant led to the accident. No radiation is believed to have leaked outside the facility, and sources at the Defense Facilities Administration Agency said Fukui Prefecture officials did not see a need for Self-Defense Forces elements to be dispatched to the town to assist in disaster relief. The accident occurred during regular maintenance in a facility housing the reactor turbines, according to Kepco. The dead and injured were all employees of Kiuchi Keisoku, a subcontractor based in Tennoji Ward, Osaka. [The company] said there were about 200 people in the facility.

Those subcontractors, it turns, may be the real victims of the industry – and of the accident at Fukushima.

Next: The “nuclear gypsies.”

[…] In “Japan, Democracy, and the Globalization of Nuclear Power,” Tim Shorrock, an independent journalist and blogger on Asian Pacific issues gives an excellent and critical account of the origins and rise of Japan?s nuclear industry: […]

[…] regarding the ins and outs of the nuclear power system, but for anyone wanting a primer, I suggest this post from journalist Tim Shorrick (who grew up in Japan and has been a longtime researcher into nuclear […]