Nuclear Gypsies – The subcontractors who do the dirty work

As the six reactors at Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Fukushima power complex have burned out of control over the past week, both the foreign and Japanese press have been full of stories about the “Fukushima 50” – the several hundred workers who have valiantly, in shifts of 50, struggled to contain the fires and in the process exposed themselves to serious risks of radiation. They have been rightly hailed as the unsung heroes of Japan’s earthquake, tsunami and nuclear catastrophe, as noted by the London Guardian:

As the six reactors at Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Fukushima power complex have burned out of control over the past week, both the foreign and Japanese press have been full of stories about the “Fukushima 50” – the several hundred workers who have valiantly, in shifts of 50, struggled to contain the fires and in the process exposed themselves to serious risks of radiation. They have been rightly hailed as the unsung heroes of Japan’s earthquake, tsunami and nuclear catastrophe, as noted by the London Guardian:

[In Fukushima], plant workers, emergency services personnel and scientists have been battling for the past week to restore the pumping of water to the Fukushima nuclear plant and to prevent a meltdown at one of the reactors. A team of about 300 workers – wearing masks, goggles and protective suits sealed with duct tape and known as the Fukushima 50 because they work in shifts of 50-strong groups – have captured the attention of the Japanese who have taken heart from the toil inside the wrecked atom plant. “My eyes well with tears at the thought of the work they are doing,” Kazuya Aoki, a safety official at Japan’s Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency, told Reuters…

On Wednesday, the government raised the cumulative legal limit of radiation that the Fukushima workers could be exposed to from 100 to 250 millisieverts. That is more than 12 times the annual legal limit for workers dealing with radiation under British law. (UPDATE: See the latest article from the Guardian – “The truth about the Fukushima ‘nuclear samurai.'”

As I noted in my first article in this series, many of the workers exposed to radiation in nuclear accidents over the years have been subcontracted workers who are often hired to do the dirtiest and most dangerous work in the nuclear industry. This has created a two-tier labor system in Japanese nuclear power plants, with a narrow band of full-time company employees at the top and a huge number of subcontractors at the bottom (click here for a profile of “Koji,” one of the subcontractors at the Fukushima complex).

As I noted in my first article in this series, many of the workers exposed to radiation in nuclear accidents over the years have been subcontracted workers who are often hired to do the dirtiest and most dangerous work in the nuclear industry. This has created a two-tier labor system in Japanese nuclear power plants, with a narrow band of full-time company employees at the top and a huge number of subcontractors at the bottom (click here for a profile of “Koji,” one of the subcontractors at the Fukushima complex).

For years, these workers have been known as “genpatsu gypsies,” or “nuclear gypsies,” because they often travel from plant to plant as needs for their services rise and fall. Their stories make some of the saddest tales of all in the Japanese nuclear industry (they’re not alone; a friend of mine at the Teamsters Union in Washington tells me the same kind of two-tiered system exists in the U.S. nuclear industry as well.”)

The plight of the nuclear gypsies has been well documented. One of the most detailed articles was published 12 years ago in the Los Angeles Times (“System of Disposable Workers,” Column One, December 30, 1999). It described the system this way:

The elite engineers and highly skilled unionized workers at the top of the labor pyramid, who work for the blue-chip giants that build and operate Japanese nuclear power plants, are carefully monitored and protected from radiation exposure. However, the majority of nuclear plant workers are employed by subcontractors or their subcontractors, an arrangement that allows big corporations to avoid major layoffs of their own people in hard times. Critics say this system diffuses accountability, makes it impossible to keep tabs on the health of workers and places responsibility for safety with smaller, less visible and financially weaker companies.The workers at the bottom of the socioeconomic food chain–including those allegedly hired by the day from skid rows–receive the least safety education and the highest radiation doses. According to data from Japan’s Nuclear Safety Commission, of the 71,376 Japanese who are employed in the nuclear power industry, 63,420, or almost 89%, work for subcontractors. It is these employees who receive more than 90% of all radiation exposure.

Moreover, the casual laborers included among those subcontractor employees have scant legal protection, activists charge. And historically, they have received little or no compensation when accidents or illnesses occur. “Nuclear labor in Japan is a human rights problem,” charged photojournalist and author Kenji Higuchi, a nuclear foe who has spent 27 years documenting alleged safety abuses. “The whole system is based on discrimination…When you go inside a nuclear power plant, it means you are going to be exposed to radiation. You are paid to be exposed.”

In 2000, the problems of these subcontract workers was documented by Nagamitsu Miura, a professor at Tsuda College in Tokyo:

Since the first nuclear power station in Japan began operation in 1966, nuclear plants have been maintained not only by engineers but by a variety of other workers. According to the Central Registration Center of Radiation Workers, the number of nuclear plant workers in Japan in the fiscal year 1999, amounted to 64,922. About 10% of them are full-time workers employed by nuclear companies while 90% are subcontracted workers.

Thus, the vast majority of the nuclear industry’s labor force is comprised of temporary employees who work at plants for between 1-3 months at a time. These people are mostly farmers, fishermen or day laborers seeking to supplement their incomes or simply to get by. Some of them are homeless. They work mainly at nuclear power plants, but they also find jobs at nuclear fuel facilities (refining, processing, reprocessing and using plants), and at nuclear waste burial and storage facilities. The workers work twice or thrice a year at the same nuclear plant or move about to other plants. Thus, the nickname they have been tagged with by journalists, “genpatsu gypsies” (ie., nuclear nomads).

In going through my archives on the Japanese nuclear industry, I found a remarkable article in a 1980 issue of AMPO magazine (see Part One) that reviewed three recent books about the nuclear gypsies – publication of which “caused a sensation in Japan.”  One of the books was a documentary written by journalist Horie Kunio, who had “voluntarily worked for a subcontractor in order to learn the actual conditions of the nuclear power plant workers and was himself exposed to nuclear radiation.” Among the places Horie worked was Tokyo Electric Co.’s now-infamous Fukushima No. 1 Nuclear Power Plant. According to his book, as recounted by AMPO:

One of the books was a documentary written by journalist Horie Kunio, who had “voluntarily worked for a subcontractor in order to learn the actual conditions of the nuclear power plant workers and was himself exposed to nuclear radiation.” Among the places Horie worked was Tokyo Electric Co.’s now-infamous Fukushima No. 1 Nuclear Power Plant. According to his book, as recounted by AMPO:

Workers are recruited from all over the country attracted by a daily wage of 5,000 to 10,000 yen and sent into the plants with hardly any knowledge of radiation. (Until a few years ago the workers were recruited from slums such as Sanya in Tokyo, Kamagasaki in Osaka and buraku – where Japanese outcasts live – in the Kansai area.

Their work includes washing work uniforms which have been contaminated with radiation; mopping up radioactive water; scraping out shells and sludge attached to drains; inspection and repairing, mainly removing radioactive dust from the hundreds of parts inside the reactors. These operations are carried out in a small hole surrounded by radioactivity where workerrs can hardly move, and the workers are often not able to leave to go to the toilet during these operations…At the Mihama Nuclear Power Plant of Kansai Electric Power Co., where Horie used to work, a worker is required to apologize to the parent company if he gets injured.

Another book reviewed by AMPO tells the story of Morie Shin, who worked as a subcontractor of TEPCO:

[He] tried very hard to form a union in order to improve their working contitions, because of the fact that the amount of radiation dosage was one of the criteria for evaluating the workers. But he failed, and finally resigned from the company…Being afraid of pressure from the electric company, he does not reveal his real name.

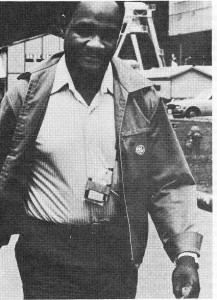

According to Morie, many of the Americans subcontracted by General Electric at the Fukushima plant were African-American (this photograph depicts a black GE subcontractor at the Fukushima plant in 1980). AMPO wrote:

According to Morie, many of the Americans subcontracted by General Electric at the Fukushima plant were African-American (this photograph depicts a black GE subcontractor at the Fukushima plant in 1980). AMPO wrote:

Morie shows in detail how the conditions in nuclear power plants make irradiation control difficult. Tokyo Electric’s Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant is said to be the most contaminated nuclear power plant in the world, and Japan Atomic’s Tsuruga plant (scene of a major accident in 1981) is also notorious for its loose radiation control…It is naturally subcontracted workers (and a “foreigners squad” of black workers sent from the U.S. by General Electric and Westinghouse) who are to work under such a high radioactive dose.

RESOURCE: AMPO – “Voices from the Darkness” – 1980

According to the IAEA, half of the 19 workers suffering from radiation exposure in the current crisis at Fukushima are subcontractors. On March 17, the Guardian reported:

More than 20 Tepco workers, subcontractors, police and firefighters have been reported to the International Atomic Energy Agency as having radiation contamination, according to Yukio Edano, the government’s chief spokesman. Seventeen people had radioactive material on their faces but were not taken to hospital because the level was low. Two policemen were decontaminated after being exposed and one worker was taken offsite after receiving a dose of radiation while venting radioactive steam from one of the reactors. An undisclosed number of firefighters are said to be under observation after being exposed. At least 25 Tepco workers and subcontractors are being treated for injuries sustained in explosions at the plant and other accidents.

[…] http://timshorrock.com/?p=1254 http://www.jca.apc.org/web-news/corpwatch-jp/96.html http://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/tsunamiupdate01.html […]

This is a fantastic article, Tim, and one that I think more people should read. Thank you for researching it and putting it together.

A few days ago a friend of mine said how disgusted he was that a German magazine had claimed that children and homeless men had been recruited by Fukushima and other nuclear plants to do the “dirty” work- he thought it was racist. I wondered if it was too- a kind of narrow-minded assumption that Japan uses ‘lesser’ members of society to take the hit. You’ve convinced me otherwise.

Thank you for sharing your priceless experience and knowledge about TEPCO and working conditions at Fukushima. I am writing a short magazine article for a Green Party magazine here in the States, and I hope to use some of your observations in it. God bless!