A report on Michael Moore’s first stop on his “living room” book tour – in which I ask him something about Nader I’ve been burning to know for years.

A report on Michael Moore’s first stop on his “living room” book tour – in which I ask him something about Nader I’ve been burning to know for years.

Last Friday I had the good fortune to be invited to Michael Moore’s first stop on his national “living room” reading tour, in which he is promoting his new book Here Comes Trouble to local journalists and activists in cities around the country. My invite came from Mike Elk, the labor beat reporter for In These Times and other publications, who often cross-posts his stories on Moore’s website. Early that morning, he sent out several dozen invitations to his DC friends and colleagues, and it looked like all of them showed up in his back yard in the old hippie/leftie enclave of Mount Pleasant in northwest Washington.

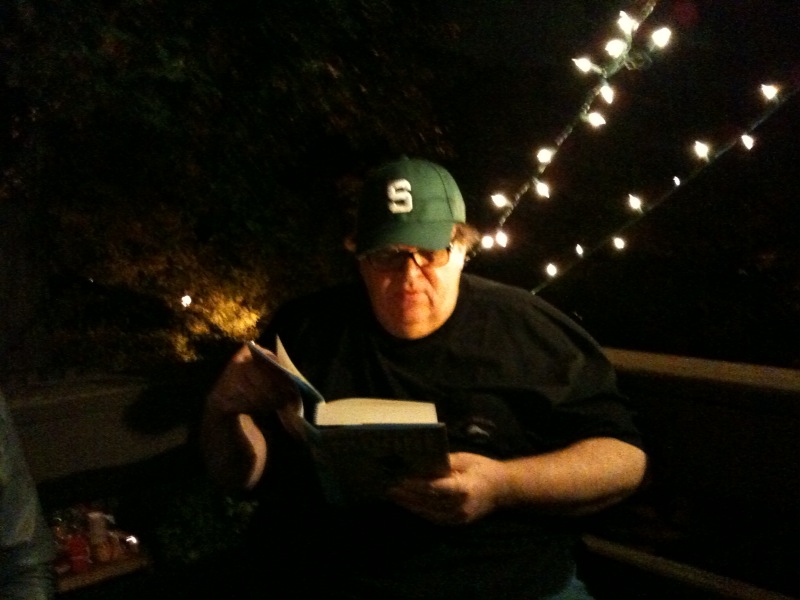

Most of them were 20- or 30-somethings, and Moore, myself and my girlfriend were by far the oldest ones there. We were joined by Moore’s security posse, which included three beefy-looking guys said to be former SEALs (one of whom stationed himself in the kitchen all night), and a retinue of assistants and advisers – chief among them Moore’s sister, Anne. A Washington-based reporter for the Irish Times, at the event to write a profile on Moore, paid close attention and typed on her laptop throughout. After a somewhat awkward entrance to the back porch and a great shifting of seats, lights, and places to stand, Moore picked up his book. “OK, boys and girls, time for your bedtime story,” he began with a chuckle.

It wasn’t your ordinary reading. Moore immediately began riffing on remarks from the crowd, which by the time he began had ingested large quantities of beer and wine. He talked of how he got into filmmaking through his friend Kevin Rafferty, who made an incredible movie in the 1980s called Atomic Cafe that documented the culture that grew up around nuclear weapons during the Cold War (see the film in its entirety here). Rafferty had told this otherwise serious story with humor and wit, something Moore had never seen before in a documentary. At the time, Moore had just been fired by Mother Jones magazine because of differences over the U.S. war in Nicaragua and was working in DC for Ralph Nader. He sought out Rafferty, who taught him “the technical work” that goes into filmmaking. One of the most important lessons he learned, Moore recalled, was Rafferty’s interest in catching what you see “in your peripheral vision. Because sometimes what you’re looking for is in the margins.” I totally agree – and have found that’s as true for filmmaking as it is for any kind of journalism.

Moore then read from the last chapter of Here Comes Trouble. It’s a hilarious account of his accidental discovery about Rafferty’s heritage during the sparsely-attended inauguration of President George H.W. Bush in January 1989 (“there was nobody there,” he laughed, something I can attest to as a witness to the event). Rafferty, it turned out, was Bush’s nephew, and therefore George W. Bush’s first cousin. Ah, the ironies: the story got a long, good laugh, including from Moore himself. “Couldn’t believe it: his uncle was Bush!”

From there the talk shifted here and there, touching on everything from his relationship with Michael Bloomberg – who once invited Moore to the White House Correspondents Dinner on behalf his eponymous news service – to what young activists can possibly do in these times of political and economic crisis. At one point, he took the time to ask everyone in the audience who they were and what they did. He spoke proudly about how many of his colleagues from his classic show TV Nation – who learned their filmmaking ropes from Moore just like he learned them from Rafferty – had gone on to work as producers and writers on such shows as 30 Rock, The Daily Show, The Late Show with David Letterman and Real Time with Bill Maher (where Moore appeared on September 24). Prodded by one despairing activist to speak “not as the Messiah” but as himself on the possibility of political change, he insisted optimistically that “it will happen,” and spoke of the hope he’d witnessed that week at the Occupy Wall Street protests in New York. Later, he expanded on those thoughts with the Irish reporter, telling her “we live in a liberal country” – a theme he hammered on this week in an interview on MSNBC’s Hardball with Chris Matthews. And, asked what he wanted to concentrate on next, he said: “I want to talk about fundamental core issues.” Excellent, I thought; but now I had some questions.

Michael and Me

I first met Michael Moore in 1984 in San Francisco, at a house of a mutual friend who worked for the Center for Investigative Reporting. He was giving a talk and slide-show on Nicaragua, where he had just spent a few weeks reporting for his paper, The Michigan Voice. Our host had two media passes to the 1984 Democratic Convention, which was going on that week. That evening, about ten of us made our way to the Moscone Center and used the passes to get all of us onto the floor one by one (security wasn’t anything like it is today). All I remember is standing in a cramped hall and hearing Ted Kennedy give a rousing speech just before the convention nominated Walter Mondale as its candidate to challenge Ronald Reagan (he got creamed). Years later, in 2002, Moore used my investigative article for The Nation on the Bush-connected Carlyle Group in his research for his great film Fahrenheit 9/11. So we’ve had a connection for a while.

But there was another connection I had to ask him about. When I first met Moore in 1984, I has just been fired by Ralph Nader from his magazine Multinational Monitor for attempting to organize a union in his shop and taking a more radical line on foreign policy, labor and economics than Nader was comfortable with at the time. The career-altering episode also involved red-baiting and political cowardice and revealed to me the true face of one part of the Washington “left” – and, of course, of Nader himself).

So I was more than a little startled to hear Moore, at the beginning of his talk, describe how he came to Washington in 1985 at the request of Nader and the Monitor to do some reporting on NAFTA and Mexican workers (all told, he ended up working for Nader for about two years). During that time, he fondly recalled, he spent a lot of time in Mount Pleasant, which was (and still is) a haven for the small army of low-wage activists who work for Nader groups and other “public interest” organizations.

Well, I had to pipe up. I informed Moore that I, too, was living here at the time, after being fired from the Monitor. I filled him in on some of the details of Nader’s obscene campaign against me after my firing, which included trying to get me arrested and a ludicrous lawsuit against me, my fired colleagues and a supporter from the Institute for Policy Studies (they dropped their lawsuit in return for us dropping our unfair labor practices complaint with the National Labor Relations Board). Moore listened intently, and said yes, he’d heard about the incident.

Later on, after the crowd had dispersed, I asked him if he had ever been informed by Nader and his people about the Monitor purge. After all, it wasn’t that much different than his firing from Mother Jones. No, he hadn’t, he said. I guess they managed to keep the news from him – which was not easy because it had been widely reported, including in the Washington Post a few months before he arrived in DC (download a PDF of the story here: Editors Claim Firing by Nader Based on Unionization Attempt, June 28, 1984).

Moore told me he wasn’t surprised by my story, and went on to describe his own dismal encounter with Nader after Moore received a big advance from Doubleday for a book he wanted to write about GM and the auto industry. That apparently didn’t sit well with Nader, who, in a fit of jealousy, confronted Moore about the advance and told him in a fit of anger to leave. “I never forgot that,” Moore said.

But Moore’s primary message about these incidents and other personal setbacks he heard about was that the left needs to stop attacking itself and turn its passion on its real enemies: the Republican Party and the big banks and corporations that run the country and fund the right. When a rather inebriated woman got into a tirade about how she’d recently been fired and what she should do about it, he replied “move on. Learn from it and move on.” If he hadn’t been canned from Mother Jones or kicked out of the Nader organization, he said, he’d never have made his first film, Roger & Me. And pointing at me, he said: “And if he’d never been fired, he’d never have gone on to be a business journalist or write a book.” Which was true – I went on after my experience to learn the reporting trade as a business and labor journalist, and in 2008 published my first book – SPIES FOR HIRE: The Secret World of Intelligence Outsourcing. And now I work for one of the biggest public-sector unions in the country – another experience that grew directly out of my contacts with the DC labor movement during and after my days with Nader.

As for Nader, Moore said, despite his foibles, we on the left should never lose sight that he’s responsible for helping democratize and humanize America through his campaign for auto safety, the environment and consumer rights, and his role in founding Public Citizen and other organizations. When I remarked that my experience with Nader during the 1980s was colored in part by Nader’s conservatism on foreign policy during the Cold War, Moore replied that Nader had begun to change in the late 1980s. He described how Nader, without any publicity, had funded Amy Goodman, Moore and others to visit the Middle East during the first Intifada to learn “what was really happening with the Palestinians.” That’s true, I replied, and I remembered too that he’d funded the journalist Allen Nairn in his quest to investigate the sordid ties between the U.S. military and the dictatorial Suharto regime in Indonesia. And yeah, Public Citizen – which now has no formal connection to Nader – is finally a union shop; all it took was 20 years. All good – but those gestures have never been enough for me to change my mind about the guy.

Still, I agree with Moore on looking beyond Nader’s failures as an activist and political leader – even his quixotic campaigns for the presidency in 2000 and 2004 (Moore backed him in the first run but literally begged him not to repeat the performance four years later). And yes, the left does “eat its young.” But it – we – also need to be clear-eyed and honest about our failures and misdeeds and not to overlook such things as union-busting at public interest organizations or cowardice in the face of the right. A broad coalition for a more democratic and equitable America, and against corporate greed, demands both respect for our differences as well as honesty about our failures. Without a full apparaisal of our stengths and weaknesses, we are bound to remain divided and powerless. We must speak truth to power, no matter who’s in control.

In the end, I think Michael Moore’s message of hope, courage, forgiveness and activism is the perfect antidote for the Plutocracy in our country right now – though I do think he’s a little over-optimistic on America as a “liberal” nation. But as I tweeted after his “living room” reading, he’s as real in person as he appears on the media – and funny, direct, personable, respectful, curious and always hopeful. Thanks, Michael, for all that you do! And Ralph, if you want to make the peace sometime, I’m ready if you are. But a little apology might be in order first.

Washington, D.C./October 4, 2011