In an extraordinary and undemocratic act, the South Korean government has prevented Lee Jong-Hyeon, a 79 year-old Korean living in Germany to enter the country to attend commemoration ceremonies remembering the May 18, 1980, uprising in Kwangju. He arrived on May 12th and was expelled on May 13th. According to the Hankyoreh newspaper,

In an extraordinary and undemocratic act, the South Korean government has prevented Lee Jong-Hyeon, a 79 year-old Korean living in Germany to enter the country to attend commemoration ceremonies remembering the May 18, 1980, uprising in Kwangju. He arrived on May 12th and was expelled on May 13th. According to the Hankyoreh newspaper,

Lee had been officially invited to attend the Asia Forum, which [opened] in Gwangju on May 17, organized by the May 18 Memorial Foundation. He had been planning to stay in South Korea until May 19, during which time he would have attended the May 18 memorial ceremony and given a presentation about the democratization movement in Germany since the 1980s. Lee has visited South Korea in 1990, 1994, 2004 and 2010, and this is the first time he has been refused entry.

Today I received a dispatch from Ok-Hee Jeong, a journalist based in Berlin, based on an interview she conducted with Mr. Lee shortly after he returned to Germany. Her story is reprinted here, with permission. It was translated by Ian Clotworthy.

The South Korean State‘s Fear of An Old Man

By Ok-Hee Jeong

Lee Jong-Hyeon remains in shock. The South Korean native, a citizen of Germany and resident of Duisburg for the last forty years, was detained upon arrival at Incheon Airport and deported back to Germany the next day. The right to enter Korea was refused, in accordance with articles 11 and 12 of the South Korean immigration law, which states, “there is justified concern, that he will harm the state and poses a danger to public life.“ To Lee, that is ridiculous. “How can an old man like me pose a danger to public life?“ he asks.

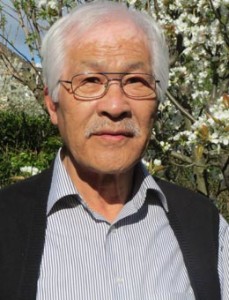

Lee came to Germany as an immigrant worker in the 1960s. Like many other South Koreans at the time, he worked as a coal miner in the industrial western Ruhr area. Later, he went to college, married a German woman and had two children. This short man with snow-white hair is now a grandfather, and enjoys a quiet retirement with his wife Ursula.

Although well-integrated in German society, his heart has always been in his homeland. When he left South Korea, the country was under the authoritarian rule of Park Chung-Hee, father of current president Park Geun-Hye. Together with other South Koreans and Germans, Rhee created organizations that campaigned for democracy and peaceful reunification in Korea.

When the dictator Park Chung-Hee was killed by his own secret police chief Kim Jae-Kyu in 1979, there was a new wave of hope among South Koreans, at home and abroad, that the long-hoped for era of democracy would begin. But the hope didn‘t last. In May 1980, the German cameraman Jürgen Hinzpeter captured footage of the massacre in the city of Gwangju after General Chun Doo-Hwan carried out his military coup. In this massacre, hundreds of people were brutally slaughtered; many are still unaccounted for.

Images of the atrocities of that day enraged Lee, and made him rise to the vanguard of the struggle in Germany. He worked with others to exert international pressure upon the Chun military regime and to express solidarity with the South Korean people. It fills the 79-year old with pride, that the South Koreans attained democracy in 1987 with their own power.

“I just couldn‘t believe it, when I was refused entry at the airport,” Rhee told me. “My son called the Germany Embassy in Seoul from Berlin, but the staff there said they could do nothing, that it was an internal matter for South Korea.“ Rhee felt also abandoned by his chosen homeland of Germany. In addition to disbelief, there is a mix of anger and sadness in Rhee‘s voice. “How can a government behave like this? What was my crime? I suspect, the refusal of entry has something to do with my visits to North Korea.“

He remembers the expulsion of the Korean-American activist Shin Eun-Mi from South Korea after being accused of glorifying North Korea one year ago. Her crime: mentioning that North Korean beer was delicious and that the Nakdong river was clean, in a public talk. She made those remarks in a series of talks about her travels in North Korea, which South Koreans may not visit.

For this, she was branded a North Korean sympathizer, and ordered to leave the country for five years. The accusation of being a North Korean sympathizer is taken seriously in this divided country, where anti-communism used to be a favorite tool of the Park and Chun dictatorships as they sought to silence government critics.

“The first time I visited North Korea was a conference with sixty other Koreans from abroad. Later in 1994 I was there, because my brother, who lived in North Korea, had died. During the sunshine policy of [former president] Roh Moo-Hyun‘s government in 2007, I was there at a summit of North and South Korea, with hundreds of other representatives present. But that can‘t be the reason [I was expelled this time]. I also visited South Korea in 2007 and 2010, and had no problems with entering the country. But what has happened now? he wonders.

In South Korea, the sociologist Kim Dong-Choon of Sungkonghoe university says, “our young democracy has been in retreat for 8 years, because politicians with the orientation of the 1970s cold war ideology are still in power. I think that Rhee‘s role is significant and very symbolic, so Park‘s government has used this measure to make an example of him.“

Rhee finds these developments to be worrying, and sees the refusal of entry as a further sign of the regression of democratic values. “People sacrificed their lives for democracy in our country, and now it is being hollowed out, piece by piece,” he says. But the 79-year old comes across as unrelenting. “The democracy of my homeland was so hard-won, that I cannot simply stop fighting for it! Never!” he told me.

Ok-Hee Jeong is a Berlin-based German journalist. Her articles were published, among others, in ZEIT Online, taz, FAZ (Germany) and in WOZ (Switzerland).