A few days ago, I visited Antietam Battlefield in Maryland, when over 4,000 Union and Confederate soldiers were killed in 12 terrible hours of slaughter on September 17, 1862. Even after Pearl Harbor and 9/11, Antietam still remains the scene of the bloodiest day in American history. I’ve always wanted to see the battlefield ever since I learned that my great-grandfather, Henry Eliot Savage of Berlin, Connecticut, fought and almost died there. Seeing those cornfields and gentle hills for the first time was a deeply emotional experience that I will never forget.

The battle of Antietam took place early in the Civil War after the traitorous general Robert E. Lee led his pro-slavery army across the Potomac River and marched them deep into Maryland. For the newly formed Confederate state, it was a propitious time: both Britain and France were considering formal recognition of the South as a separate nation, a move that could have been fatal to President Lincoln and the Union he was trying to protect.

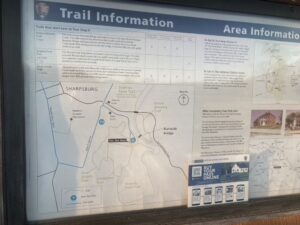

After Lee sent his army across the river, President Lincoln’s generals, led by the notoriously cautious General George B. McClellan, were unsure of his intentions. So they sent a large chunk of the Union Army into Maryland to check his movements and drive him back to Virginia. After a fierce series of bloody skirmishes on South Mountain, where Lee had sent some of his forces to block the roads and slow the Union advance, the Confederates regrouped around the rural town of Sharpsburg, just across the Potomac from Shepardstown (now part of West Virginia).

A fortuituous find: Lee’s Special Order #191

Their aim was to press up through Maryland and into Pennsylvania and force a Union surrender. In a stroke of luck, Lee’s famous Special Order #191 revealing his plans and objectives (and wrapped with a package of cigars) was discovered by a unit of Union soldiers and sent up the chain to McClellan.

Among the revelations in the order were Lee’s plans to capture thousands of Union soldiers stationed in Martinsburg, Virginia, and the federal garrison at Harper’s Ferry to weaken McClellan’s position. It also provided the exact locations of every command in Lee’s Army. With that information, McClellan decided to encircle the Confederate invaders, and sent his army to confront them. The stage was set for the mass slaughter on September 17th.

One of the soldiers sent to Antietam was Henry Savage, my mother’s grandfather. With 20 pages of information provided by a kindly National Park Service ranger, I was able to trace nearly every moment of his experience that day. I learned that he was part of the 16th Connecticut Infantry that was mustered into Federal service in Hartford on August 24, 1862, just 3 weeks before the battle. On August 29, Henry’s regiment was ordered to Washington, DC, where it joined McClellan’s Army of the Potomac.

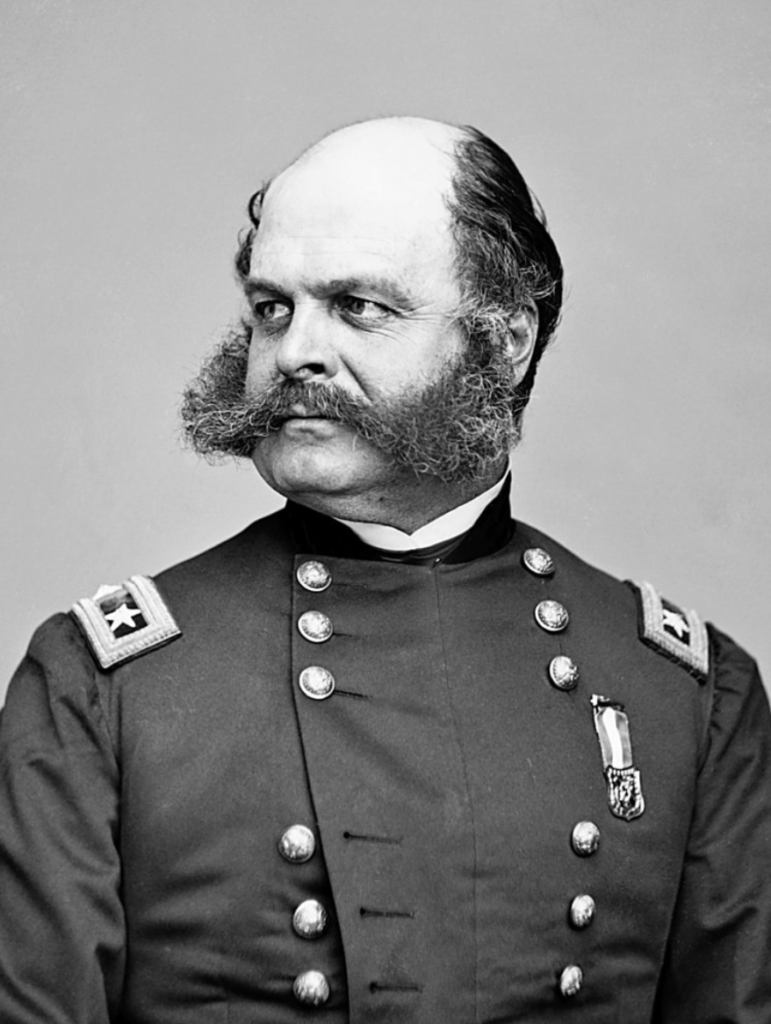

At Antietam, the 16th Connecticut was part of the Ninth Army Corps led by General Ambrose E. Burnside, a railroad executive from Rhode Island. It also included the 8th and 11th Connecticut and the 4th Rhode Island Infantry. At the start of the battle, it was waiting in reserve on the south side of Antietam Creek near the spot where General McClellan was stationed to oversee the battle.

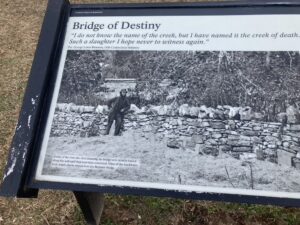

Unfortunately, that placed Henry and his 16th Infantry on the far left of the Union flanks. That would prove to be fatal when they were attacked late in the day by units led by Confederate General A.P. Hill, who had just crossed the Potomac from Harper’s Ferry. The site of that fighting is captured in the second and third photographs above.

Antietam was a massacre

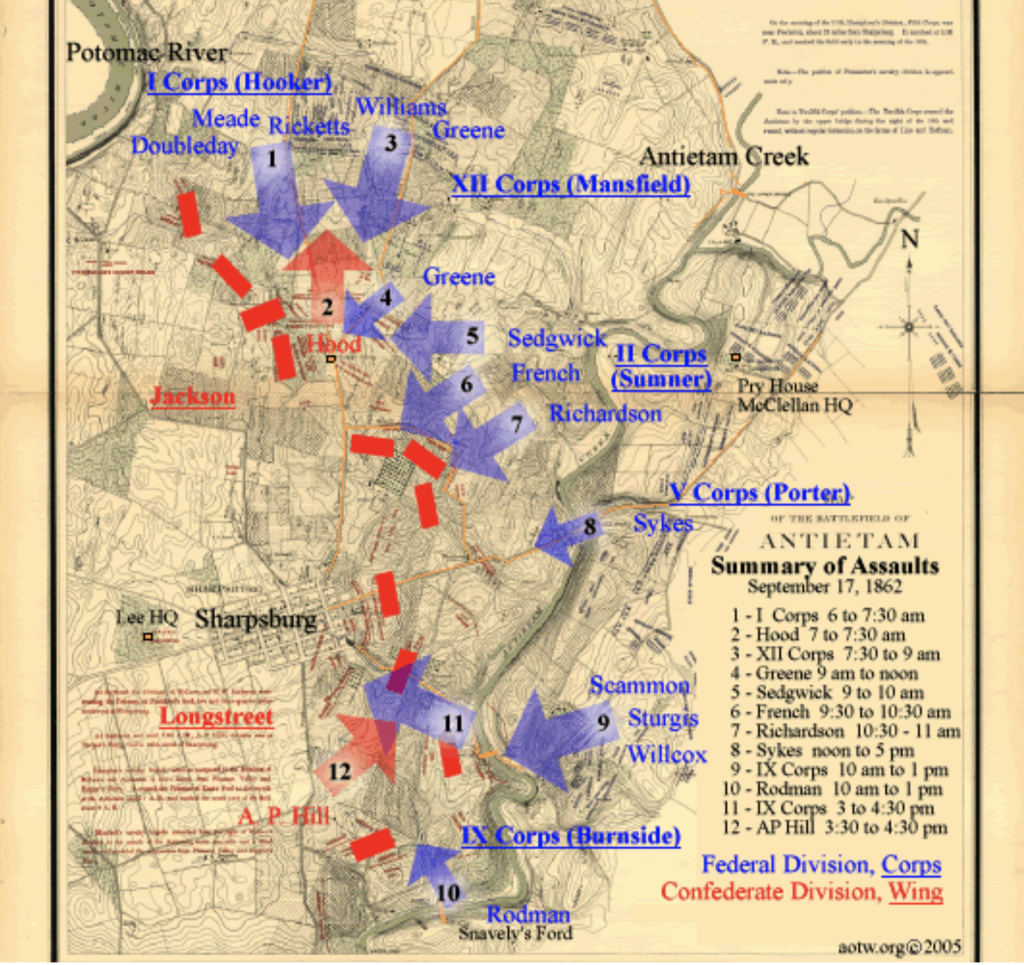

As you can see from the map below, the Union attacks on Lee’s army began early in the morning. Lines of the men in blue marched through cornfields, where they were met by the Confederates in gray. Often soldiers were shooting at point blank range, and the hand-to-hand bayonet fighting was vicious. Throughout the battle, cannons fired from the rear sent shells and shrapnel pummeling into the fighters, pulverizing bodies and exploding heads, arms, and legs. It was one massacre after another; a merciless slaughter.

About 3 hours into the terrible fighting in the cornfields, Henry’s 16th and the other units under General Burnside’s command were ordered to cross Antietam Creek and confront the Confederates – many of them from Georgia – who held the heights on the south side of the battlefield just above the now-famous Burnside Bridge pictured above. The 11th Connecticut was cut to pieces trying to take the bridge, which was eventually taken by companies from Ohio, according to tablets on the battlefield. The 16th Connecticut, with the other units, later crossed the creek at a spot just south of the bridge and marched up the hill towards the Georgians, who were pouring fire down on them.

General Burnside’s orders were to smash into the Confederate lines and divide Lee’s army. “For whatever reason,” the NPS history reads, these regiments “were late in advancing and did not keep up” with the brigades to their right, which included the 8th Connecticut. It was at this point that the Confederates under General Hill arrived from Harper’s Ferry and tore into the 16th and its fellow units. The losses were terrible.

“The rookie soldiers of the 16th Connecticut, who were mustered into service only three weeks earlier and who were now marching into battle for the first time, broke under the weight of the flank attack.” Most of Henry’s battalion was either killed or wounded. “It assisted in checking A.P. Hill’s advance but, the left of the line having been turned, it was obliged to withdraw to the cover of the ridge” above the bridge. A large tablet marks the center of the 16th Connecticut’s advance (read General Burnside’s official account of the battle here).

It was amazing to me to stand on the exact ground where Henry Savage and his 16th fought to preserve the Union. He was one of only 250 soldiers out of the 900 in his regiment to survive the single bloodiest day of the war. After Antietam, he fought in North Carolina, where he was captured at Plymouth on April 20, 1864, according to official records. He spent the rest of the year at the notorious Confederate POW camp in Andersonville, Georgia, and was mustered out of the army on June 24th, 1865.

After recovering in a field hospital in Arlington, Virginia, Henry returned to Berlin, a farming community just outside of Hartford, and ran his father’s dairy farm for the rest of his days. He had four children, including my grandfather, Theodore Savage. My mother Helen grew up on Henry’s farm on Savage Hill, which remained in the family until the 1970s. According to my relatives, Henry never talked about the war and the horrors he experienced at Antietam.

Antietam and the Emancipation Proclamation

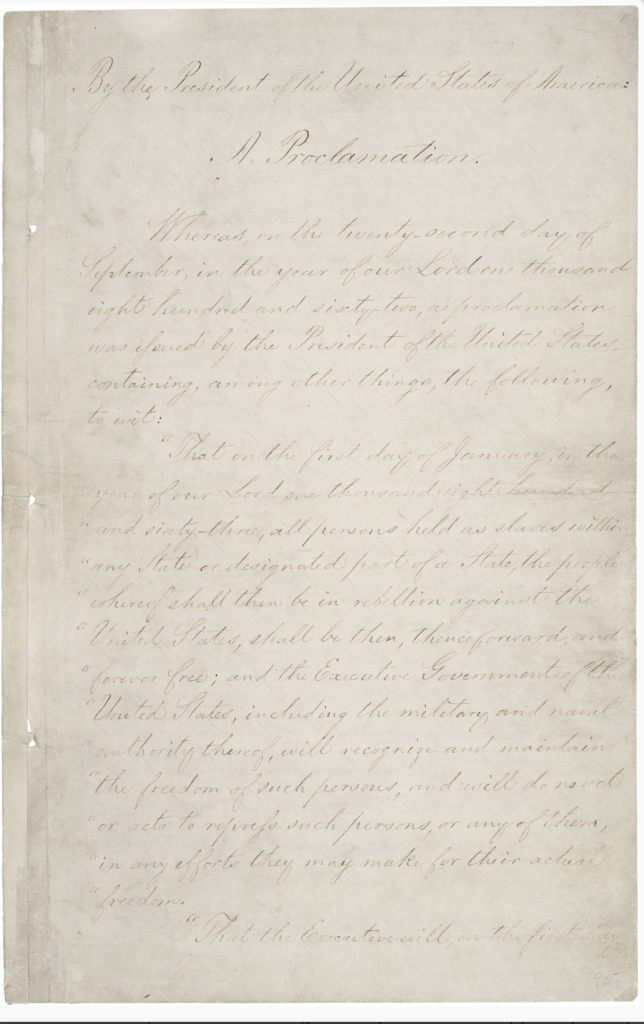

With over 4,000 dead on both sides, the Battle of Antietem was in truth a stalemate. But it was a victory in the sense that Lincoln’s Union Army forced Lee’s army to retreat back to the south and forego his plan to invade; the union was saved for now. That gave Lincoln the opportunity he had been waiting for. On September 22, he announced his intention to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. Published on January 1, 1863, it declared “that all persons held as slaves” within the Confederate states “are, and henceforward shall be free.”

With one signature, Lincoln “tranformed the war into a moral crusade and gave the conflict real meaning,” the NPS history states. “No longer was the war a mere political context fought solely to reunite a divided nation. Now…it was being fought to liberate millions of human beings from the brutal bonds of slavery.” But its impact extended far beyond the Civil War.

“In transforming the war into a moral struggle to destroy slavery, Lincoln effectively ended all thoughts of European intervention on behalf of the Confederacy. The effect was particularly strong in Great Britain, which had for the past thirty years taken great strides in eliminating human bondage in its colonies throughout the world. There was no way Great Britain would now support a confederacy fighting to retain its institution of chattel slavery.” As a result, “Confederate hopes of European intervention and support were shattered.”

I’m immensely proud of my great-grandfather Savage for being part of a struggle that ended slavery in this country and prevented the great powers from intervening in the war on the side of the South. But knowing as much as I do about the Korean War, which was essentially a civil war as well, the battle of Antietam raises difficult issues.

Imagine what could have happened if Britain or France had recognized the Confederacy as a legitimate nation, and then decided to assist in its fight against Lincoln’s United States of America by sending armaments and even soldiers? The South might have won the war, and expanded slavery from the cotton fields to the farms and factories of the North. Black people would have suffered for years into the future, and this country’s march towards full democracy for its citizens would have been stopped in its tracks. Worse, an authoritarian, racist USA would have likely sided with Nazi Germany and Fascist Japan in their savage attempt in the 1930s and 1940s to divide the world between themselves.

That leads me back to the Korean War, which has its roots in 1945, when the United States divided the country at the 38th parallel and occupied its southern half while the Soviet Union took the north. From that point on (in my admittedly over-simplified analogy) Korea became a battleground between leftist and communist factions in both south and north who wanted to create a single nation freed from Japanese colonial control, and rightist factions of landlords, Japanese collaborators, businessmen, liberals and fascists, mostly in the south. There’s no telling how this civil war would have ended without foreign intervention, but many historians believe that Korea would have remained a united country under a leftist or communist government, much like Vietnam is today.

But the outside intervention and the Cold War prevented Korean from charting their own course. When the northern leftist factions in the North crossed the 38th parallel in June 1950 and tried (with support from the Soviet Union and China) to liberate the southern government from its pro-American factions, the United States (backed by a weak and divided United Nations) intervened for the south in a massive way. After pushing the northern armies out of the south, the US military behind President Truman then re-invaded the north and brought the fight all the way to the borders of China and the Soviet Union. That, in turn, brought the intervention of Chinese military forces, who pushed the US military back across the 38th parallel. During the war, North Korea was totally destroyed by US bombing.

The war ended, temporarily, with an armistice in 1953. And today’s Korea – still divided, still technically at war – remains one of the few unresolved issues left from World War II. That’s a tragedy and one that the United States managed to avoid in its civil war. And it’s why I so admire and honor President Lincoln, Henry Savage, and the tens of thousands of people who sacrificed their lives to rid America of the scourge of slavery and maintain its unity that is so threatened today by the Trumpist, white nationalist right.

Henry Savage, Presente! Remember Antietam!