I just spent an exhilarating week with Korea Peace Activists in DC to push for an end to the Korean War after 70 years. To mark the occasion, I’ve posted an article on my experiences at the DMZ in 1960 and 2023 – 63 years apart. Lessons: The war is not over and the US Army still controls the inter-Korean border.

The Demilitarized Zone that surrounds the Korean truce village of Panmunjom is one of the saddest places on earth.

One hundred sixty miles long and two-and-a-half miles wide, it marks the last stand of two hostile armies that battled it out in this divided land at the beginning of the Cold War. And on July 27th, 1953, 70 years ago, it was the spot where military leaders from the United States, North Korea, and China converged to sign the armistice that temporarily ended the fighting of one of the most destructive wars in history.

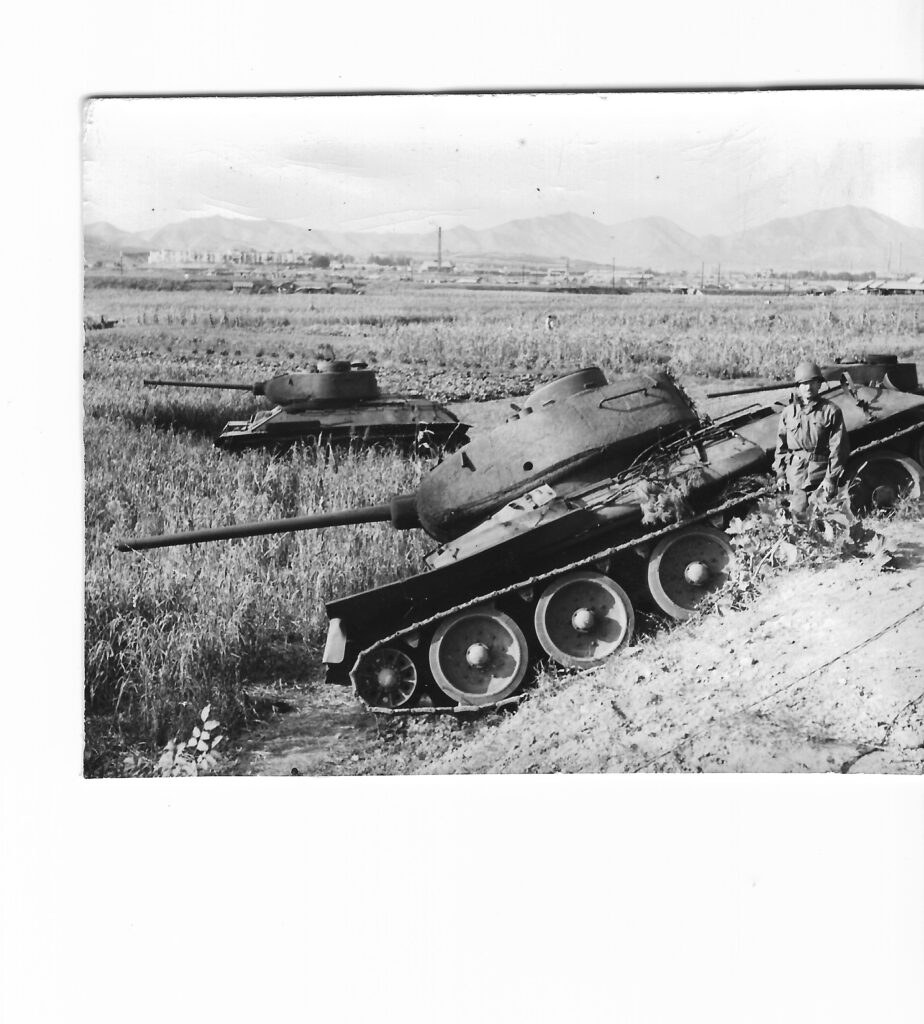

I first visited the DMZ in 1960, a year after my father moved our family from Tokyo to Seoul to run the Korea division of Church World Service, America’s largest private relief organization. To an impressionable nine-year-old, it was an unforgettable experience: the DMZ was the front line of the Cold War and offered a rare glimpse into the deadly standoff between the United States and the communist world that I heard about every day on the radio.

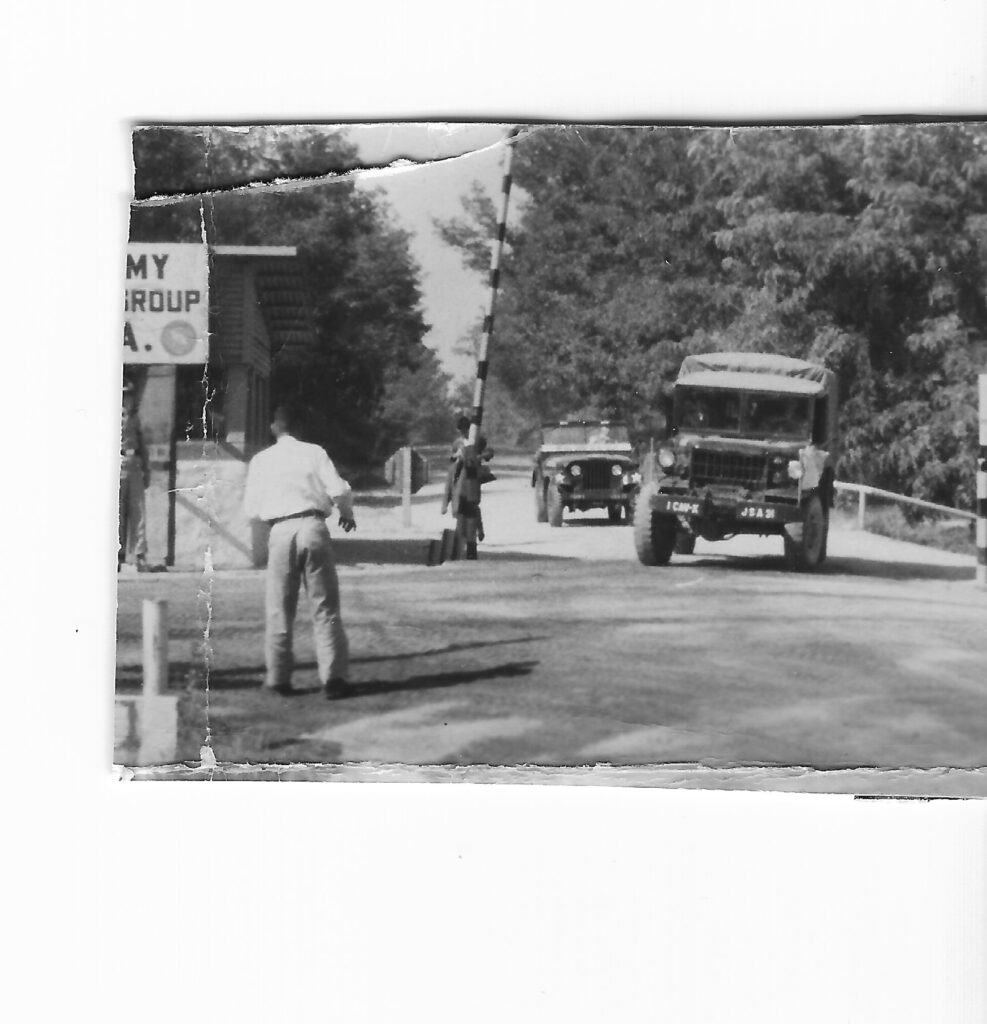

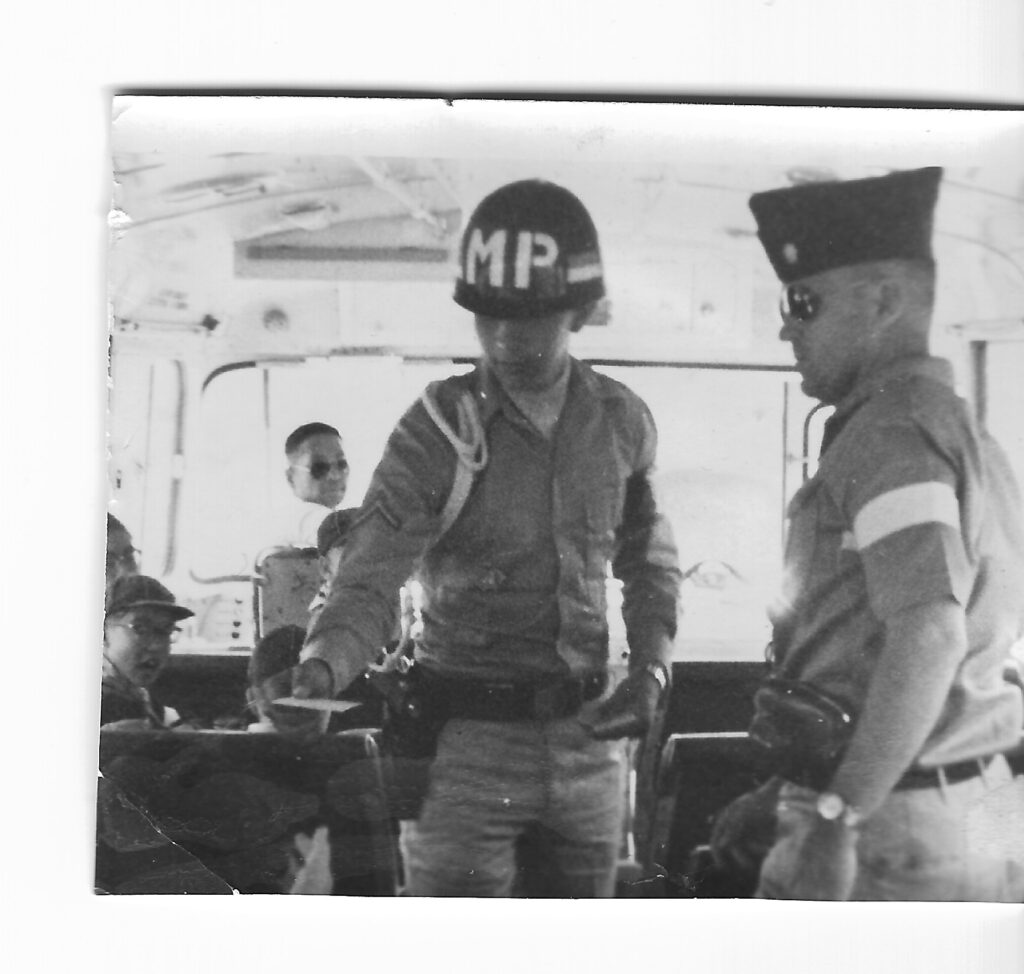

Just a few miles out of Seoul, we could see soldiers manning artillery and tanks, all with their armaments pointing north. As our school bus entered the control zone in the southern side of the DMZ, a uniformed U.S. Army officer in bright aviator sunglasses, accompanied by two Korean soldiers, clambered aboard to check our passports. Once at the border, we could see the eerie “Bridge of No Return” across the Imjin River, which thousands of POWs crossed on their way home from one of the most destructive wars in history.

From there we drove to the Joint Security Area (JSA), where blue, low-slung buildings occupy the site where the warring generals signed the armistice. It remains the only area along the DMZ where U.S., South Korean, and North Korean soldiers face off without a thick fence of barbed wire strung between them. Outside of a pagoda-shaped lookout, my dad took a picture of me with my Cub Scout uniform on, squinting in wonder at the strange scene around me.

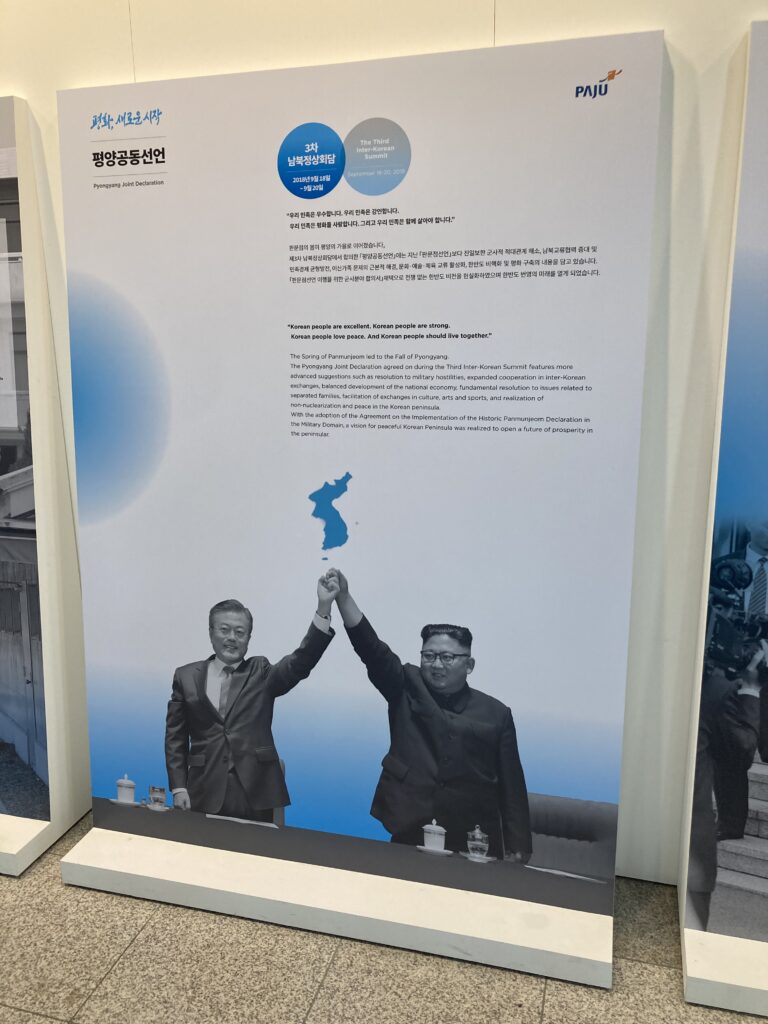

I returned to the DMZ in April 2023. The JSA was closed to foreign visitors and journalists this time, so I joined dozens of tourists on a guided tour to Unification Park near the border town of Paju. Despite a recent string of North Korean missile tests that were met by U.S., South Korean, and Japanese war games and a fly-over by American B-52 and B-1B bombers, the overwhelming emotions at the park were sorrow and regret.

Inside the information center, a sign welcomed visitors to “the world’s only divided country.” Up on the roof, we peered through powerful binoculars into the villages and hills in the forbidden North. Even with the heavy cloud cover, the once-thriving industrial city of Gaesong just across the border and the jagged mountains in the far north were clearly visible. “Korean families come here to remember because it’s the closest we can get to North Korea,” our guide, a young Korean named Laura wearing a “Dallas, Texas” sweatshirt explained. “The sad thing is, we don’t know if they’re alive or dead.”

As our bus pulled out of the DMZ, two South Korean soldiers came on board to check our passports. As Laura pointed out, they were being supervised by an officer standing outside from the “UN Command.” I think I was the only passenger to notice that he was an American soldier in a U.S. Army uniform, just like I’d seen back in 1960.

Seventy years after the armistice, the United States still controls all border movements between South and North Korea and retains 28,500 soldiers on the peninsula. For Americans and Koreans alike, the Korean War has never ended.

My next book, DMZ EMPIRE, will explain why and chronicle what has happened in the intervening years.