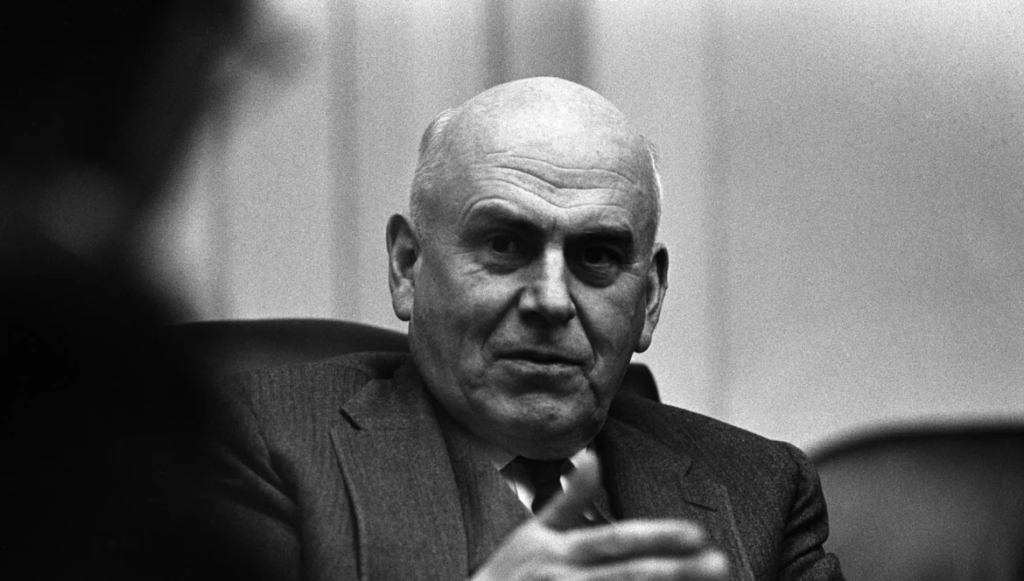

Just after midnight on August 10, 1945, barely 24 hours after a U.S. Air Force B-29 obliterated Nagasaki with the world’s first plutonium bomb. John J. McCloy, a longtime fixer in Washington and chairman of President Truman’s State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee (SWNCC), dispatched two aides to a basement office at the White House annex on an urgent mission.

With Imperial Japan about to submit to Truman’s ultimatum for an unconditional surrender, McCloy’s War Department needed to send a general order to Japan’s High Command that would define the zones in Korea, Japan’s colony since 1910, where the United States, the USSR and other wartime allies would accept Tokyo’s capitulation.

By previous agreement with the United States at Yalta, Joseph Stalin’s Red Army had entered the war in the Far East on August 8th, and was now chasing Japan’s powerful Kwangtung Army out of Manchuria. The Russian offense, dubbed “August Storm,” involved nearly 1.6 million battle-tested troops buttressed by the Soviet Pacific Fleet. They were determined to “purge the Russian Far East and nearby areas” of the Japanese presence and ensure a Soviet role in Japan’s surrender. That meant clearing the over one million soldiers Japan had deployed in Manchuria, Korea, southern Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands.

But the Russian advance unfolded faster than anyone in Washington had anticipated. As they watched from afar, Truman’s advisers feared these Soviet forces could soon occupy all of Korea. From Moscow, diplomat and railroad magnate W. Averell Harriman urged Truman to use U.S. forces to “occupy as much of Korea and Manchuria as possible.” Declassified documents would later reveal that U.S. officials were petrified that the Soviets would be accompanied by thousands of hardened Korean fighters and revolutionaries who had taken up arms against the Japanese in Manchuria.

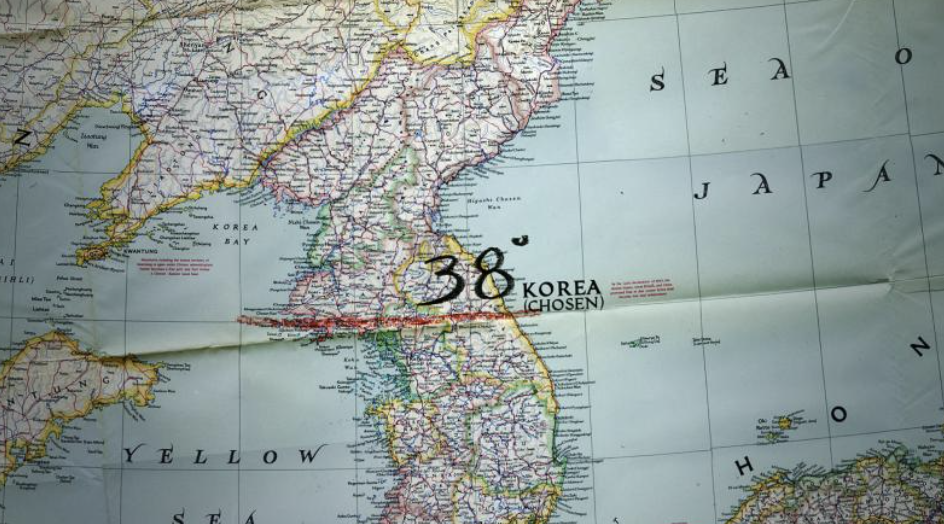

With the pressure on, McCloy’s aides, Colonel Charles H. Bonesteel III and Major Dean Rusk (who would later serve President Kennedy as Secretary of State) checked out a National Geographic map on the wall and decided that the best line of demarcation for Korea was the 38th parallel that crossed the peninsula about midway through.

Their line reflected nothing of Korean reality, and cut right through several Korean provinces. But drawing the border there left the U.S. Army in control of Korea’s traditional capital, Seoul, and the Soviets in charge of Pyongyang, Korea’s second largest city (and, until 1945, the center of missionary Christianity on the Korean Peninsula). Truman sent the proposal to Stalin, who immediately agreed.

Not a single Korean was consulted, leaving this proud country with a 5,000 year history as a single nation out in the cold for this momentous decision.

The next day, August 11, the United States issued General Order Number One. Korea was to be divided until, “in due course,” as the allies had agreed in 1942, its people were judged ready by the great powers to create a new, independent state of their own. Soviet forces were to occupy the peninsula north of the 38th parallel, while U.S. forces would take everything south of the line. With that, the framework for accepting Japan’s surrender and the capitulation of its forces in Korea was set. From here on out, Korea would be divided, its fate largely up to the dictates of Washington and Moscow.

This was a sea-change, if not a revolution, in the U.S. perception of Korea, its relationship with Japan, and America’s broader role in Asia. Bruce Cumings, the leading historian of the Korean War, has called McCloy’s directive the “first act of containment.” In fact, it was the opening salvo of a Cold War that would soon engulf Korea and the rest of Asia and, five years later, explode into another full-scale conflict.

Thanks to Truman and MacArthur, the Cold War in Korea Began Immediately

Japan’s sudden capitulation and the U.S. decision to send American forces into Korea had an immediate effect on General Douglas MacArthur, who had led the assault on the Japanese military in the Pacific and was about to launch a land invasion of the Japanese mainland. Under his original plan, Operation Downfall, tens of thousands of American troops were going to land first on Kyushu and then invade Tokyo and the Kanto Plain after an assault on the beaches of nearby Chiba.

With his new orders, MacArthur turned to the backup plan, Operation Blacklist, which was a contingency plan for a “non-belligerent occupation” of Japan and its nearest and most important colony. The final scenario divided the occupations into three phases. First, U.S. troops were to enter Tokyo, Nagasaki, Kobe, Osaka, Aomori, and Seoul (this phase was completed on September 8th). In Phase 2, the targets were Shimonoseki, Nagoya, Sapporo, and Pusan; in Phase Three, Hiroshima, Kure, Sendai, Niigata, and in Korea, Kunsan and Taegu.

Operation Blacklist, with its integration of U.S. operations in Japan and southern Korea, would set the pattern for the postwar settlement in East Asia. From here on out, the U.S. military viewed Japan and its former but still-controlled colony as one unit. This unity of purpose was reflected through every step of the U.S. invasions of Japan and Korea, including the military, civilian officials and the missionaries of America’s Protestant churches.

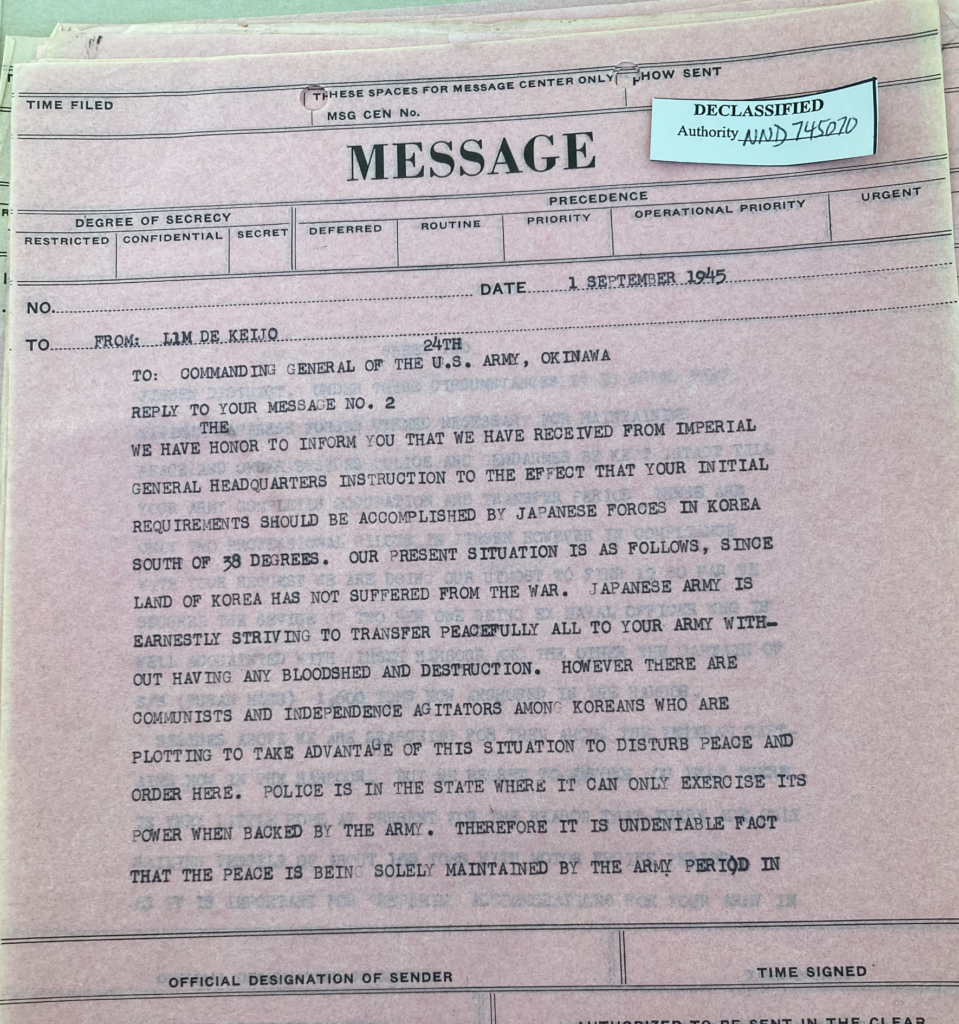

In Korea, the plan was carried out by General John R. Hodge, the commander of the U.S. Army’s XXIV Corps in Okinawa. He had been part of the giant invasion force that had defeated the Japanese army on one of the bloodiest battles of World War II (“hell on earth,” Okinawans call it today). MacArthur gave Hodge orders to contact the Japanese commander in southern Korea, who was more than happy to turn his portion of Korea over to the U.S. military instead of the grassroots, anti-Japanese Peoples’ Committees that had already formed a rudimentary government throughout the peninsula after Liberation Day on August 15.

This cable to General Hodge from the Japanese military in Seoul, dated September 1, 1945, underscores the volatile politics of the situation. “JAPANESE ARMY IS EARNESTLY STRIVING TO TRANSFER PEACEFULLY ALL TO YOUR ARMY WITHOUT HAVING ANY BLOODSHED AND DESTRUCTION,” it declares. “HOWEVER THERE ARE COMMUNISTS AND INDEPENDENCE AGITATORS AMONG KOREANS WHO ARE PLOTTING TO TAKE ADVANTAGE OF THIS SITUATION TO DISTURB PEACE AND ORDER HERE.” (I found this cable at the National Archives). Hodge, who knew virtually nothing about Korea, followed his counterpart’s advice closely.

In Japan, MacArthur had decided to allow the wartime government to remain in place. In Korea, Hodge’s U.S. Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) banned the Peoples’ Committees and then appointed an advisory government largely made up of right-wing nationalists, landlords, and Japanese collaborators. The U.S. civil affairs specialists who had been in training for years to run a Japanese government under MacArthur’s occupation were instead sent to Korea to work for Hodge.

“In Japan, initially, this would mean utilising the non-military officials and institutions that had supported aggression and, in Korea, the colonial regime and its military and paramilitary minions,” the Japanese historian Takemae Eiji would note in 2002. “America’s Japan policy would become the centrepiece of a grander strategy for containing the Soviet Union, and later China, and for enforcing a Pax Americana along the great arc of the Pacific Rim, from the Aleutians through Japan, southern Korea, Okinawa and Formosa and as far south as Indo-China.”

Today, Korea is still divided, and the two sides created by the line drawn by McCloy, Bonesteel, and Rusk remain in a technical state of war. For Koreans, that is the lasting impact of Nagasaki. The rest is history.

Sourcing: Bruce Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War; Takemae Eiji, INSIDE GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and Its Legacy.

Excellent material. I have spent time actually looking and reading up on events in South Korea 1945-1950. This fit perfectly. I have been trying to find any connections or communications between S. Rhee & Chiang Kai-shek since the both received US support. Thank you for a great read!

Scott