Opposition in Japan, South Korea, and Australia to the US War in Indochina

A few weeks ago, I spoke at a webinar about the movement against the U.S. war in Vietnam in Japan, South Korea, and Australia, three Pacific states allied militarily with the United States. My fellow speakers were Rowan Cahill and Bobbie Oliver of Australia, with the teach-in moderated by Terry Provance of Washington, D.C. All of were active in the antiwar movement, and reflected on its significance 50 years later. Here’s how we were introduced:

During the 1960’s and early 1970’s sustained popular opposition to U.S. intervention in Indochina developed in countries thought of as U.S. allies. US bases in Australia, Japan and South Korea supported the war effort. Australia and South Korea sent troops. In the case of Australia, opposition advanced beyond forms of verbal dissent to include a significant degree of draft resistance. Three knowledgeable observers of, and participants in, opposition will share their experiences in peace movements that were not well known to US activists.

The full seminar can be viewed on YouTube here, with my talk on Japan and Korea beginning about the 33-minute mark. I just finished writing my remarks out in full, and have added many links and photographs to guide your way through my broad discussion of US military and political ties with the two countries and how their 1965 Normalization Treaty paved the way for Korean military deployments to Vietnam and the formation in 2023 of the trilateral alliance between Washington, Tokyo, and Seoul. It’s a personalized journey into the darkness of the Cold War and the movement that sprang up for peace and justice both at home and abroad – a short version of the tale I’m writing in my next book, DMZ Empire.

Radical Japanese students fighting LDP riot squads with staves after the cops tried to break up their massive demonstrations against renewal of the US-Japan Security Treaty in 1960.

My talk begins with four points:

- The Japanese antiwar movement was one of the largest and most powerful in the world. It began during the early days of US intervention in Vietnam shortly after the Korean War and continued through the 1970s. The movement was largely focused on the role of US military bases in Japan/Okinawa during the Korean War and in Vietnam, as well as the US-Japan Security Treaty first signed in 1952 and renewed against massive protests in 1960 and 1969. It was a fight for peace as well as a struggle for independence from US hegemony and control.

- The South Korean antiwar movement was largely underground until the country, led by citizen protests, won its democracy in the late 1980s. In the period after the Korean War and during the US war in Vietnam, South Korea was under a military dictatorship led by General Park Chung Hee, who had been trained and served in the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II. Open opposition to US forces and holding anti-American views publicly was nearly impossible. It got even harder in the late 1960s, when Park sent troops to fight alongside US counterinsurgency forces in South Vietnam. The Korean movement was therefore a fight for democracy that turned into a struggle for reparations for the Vietnamese people in the late 1990s and 2000s.

- The Japanese and South Korean antiwar and peace movements were closely linked in their struggles against the US drive to militarize both countries and integrate them into the enormous American military platform in East Asia. They had a huge impact on the US conduct of the war and the Japanese and Korea public’s attitude towards Vietnam. But in the long run, they failed to bring either independence or peace. Japan now hosts the largest contingent of US troops in the world, with South Korea not far behind. The US under self-imposed Status of Forces Agreements with Japan and Korea continues to virtually occupy both countries militarily.

- I experienced and participated in the Japanese antiwar movement while I was living there in the 1950s and 1960s and reported extensively on the South Korean democratic movement in the 1980s. My introduction to Vietnam came in 1963, when I visited Saigon with my family while on an ocean voyage from Europe to Japan. During the war, I was subject to the US draft (I escaped with high lottery numbers) and was active in the US antiwar movement until the end of the war in 1975. So much of my analysis is directly from my own observations and experiences.

An Overview of Japan and South Korea’s role in the Vietnam War

From 1948 on, Japan and Okinawa, its southern-most prefecture, became the keystone for US military power in East Asia (this 1958 propaganda film from the US Army explains how). That year, the United States “reversed course” in its occupation of Japan, moving from demilitarization and democracy to focusing on the containment of communism. Almost overnight, US policy shifted from punishing Japanese officials responsible for World War II to enlisting them in the new Cold War against the Soviet Union and its allies. The shift inside Japan was symbolized by the rise of Nobusuke Kishi, who was prime minister from 1957 to 1960. Kishi was minister of commerce and industry in the wartime Tojo Cabinet that declared war on the US and labeled a “Class A” war criminal for helping run Japan’s colonial empire in Manchuria and Korea (his grandson, Shinzo Abe, was prime minister twice and was a US favorite until he was assassinated in 2022)

Muto Ichiyo, a Japanese writer who worked closely with the US antiwar movement in the 1960s, explained the Japanese shift to me in a 1981 interview in Tokyo. “The part of Japanese imperialism which was made powerless after the defeat in the war wanted, of course, to revive itself,” he said. “But they knew perfectly well that the situation had changed. They knew also that fighting against America again would be both impossible and purposeless. So they adopted a very clear-cut strategy: Japan will concentrate on the buildup of the economic base structure of imperialism, while America will practically rule Asia through its military forces.”

Japanese industry profited handsomely by supplying the Pentagon with steel, munitions and even napalm when the United States fought wars in Korea and Vietnam. Then, as Washington propped up South Vietnam’s Ngo Dinh Diem, South Korea’s Park Chung Hee, the Philippines’ Ferdinand Marcos and Indonesia’s Suharto with vast quantities of military aid, Japan kept their economies alive with financial aid and investments from Mitsui, Sumitomo, Mitsubishi and other major corporations.

The Korean War was the catalyst for the monumental shift in American policy in East Asia from peace-maker to empire-builder. Essentially, it set the stage for the total militarization of the Korean Peninsula and, later, Japan. It’s also important to remember the war also began US involvement in Vietnam. When Truman ordered US ground troops into Korea in 1950, he also began aiding the French colonial army in Vietnam and, incidentally, sent the US 7th Fleet into the Taiwan Straits to prevent China from completing its takeover of Taiwan. American policy in East Asia hasn’t changed much since then.

Much of the brutal war in Korea was carried out by U.S. forces directly from their American bases in Japan. Even today, the largest US bases in Japan and Okinawa fly the UN flag as integral parts of the U.S.-run “UN Command-Rear” established in Japan as the logistics and planning headquarters for Korea. Once the armistice was signed in 1953 (by the US, North Korea, and China), the US network of bases became the perfect jumping-off point for the war in Vietnam. The Pentagon transformed its air and naval bases in Japan, Okinawa, and South Korea into a massive platform for regional war.

South Korea’s role as a junior partner in the empire was sealed in 1965 when its military rulers sent over 300,000 troops to back up the U.S. military in South Vietnam. After President Nixon’s shift toward “Vietnamization” in 1972, the Korean forces outnumbered American troops by a two-to-one margin.

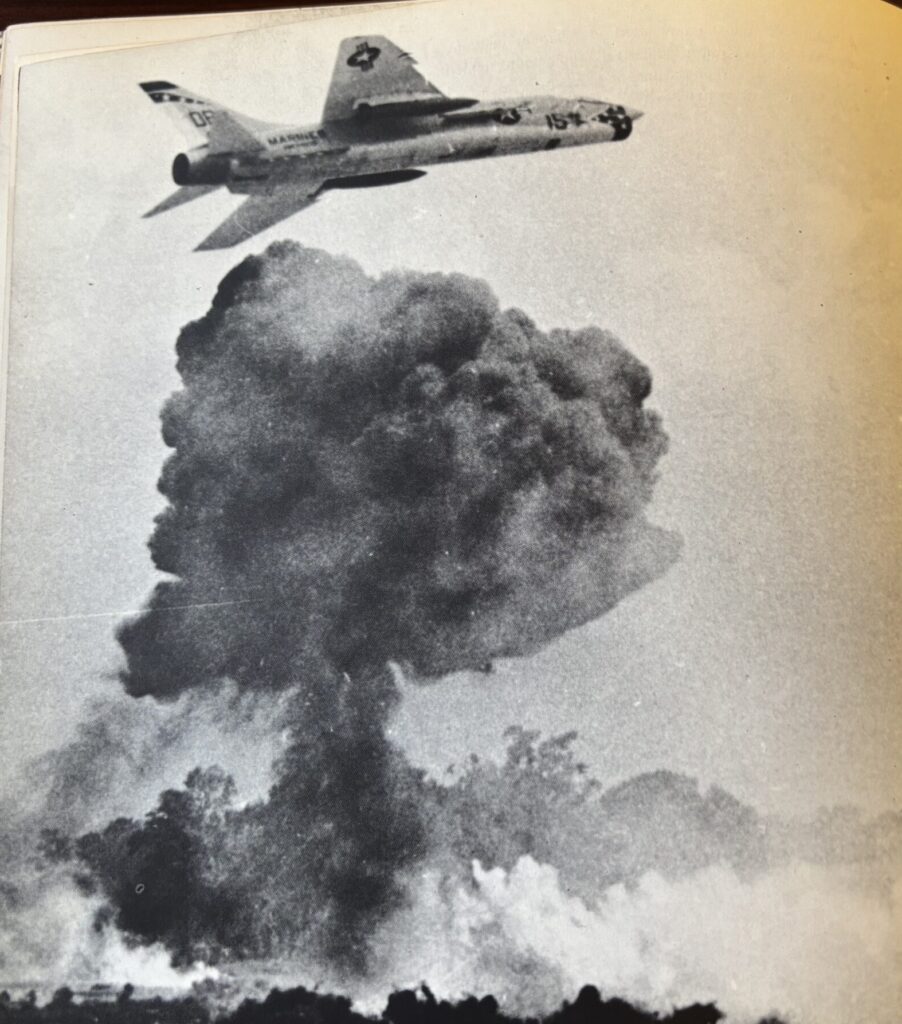

US tactics in Vietnam: Napalm and Search-and-Destroy (from VIETNAM, VIETNAM, by Felix Greene).

The antiwar movement in Japan.

The antiwar movement in Japan actually began with Korea. The Japanese people, who had suffered through the indiscriminate bombing of over 60 cities by US B-29s in the last months of World War II, were disturbed by the American use of their bases to bomb Korea and the enormous buildup of U.S. forces in Okinawa during that war. Then in 1954, the US hydrogen bomb “Bravo” dropped over the Pacific island of Bikini poisoned a crew of Japanese fishermen, sparking Japan’s first anti-nuclear movement after Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

I trace the Japanese movement against the Vietnam War back to 1956. It began at Tachikawa Air Force Base, a huge US airfield in western Tokyo that I could literally see from my family’s back porch in the 1960s (once my father drove there at 3 o’clock in the morning to meet his brother, a US Navy officer, who stopped there on his way to Vietnam).

In 1955, a year after Bikini, the US military announced plans to use Tachikawa for transporting nuclear weapons. To do that, it needed to use the surrounding farmland for longer landing and takeoff distances. In response, farmers, villagers, students, unionists, and Buddhist priests in Sunagawa, the small village adjacent to the base, began a campaign of nonviolent protests and occupation of the farmland. Tens of thousands of people, including Diet members from the Socialist and Communist parties, joined the Sunagawa protests, which forced the US military to cancel the expansion in 1957. Even after the base was turned over to the Japanese “Self Defense Forces” (SDF), it was a scene of struggle when activists – some of whom were jailed – protested Japan’s use of it to support the US invasion of Iraq. The movement to support the Tachikawa activists continues even today.

But after this, the US simply built bases for nuclear bombers in Okinawa, which remained under US military rule until 1972. The anti-base struggle at Tachikawa set the pattern for many of the protests during Vietnam.

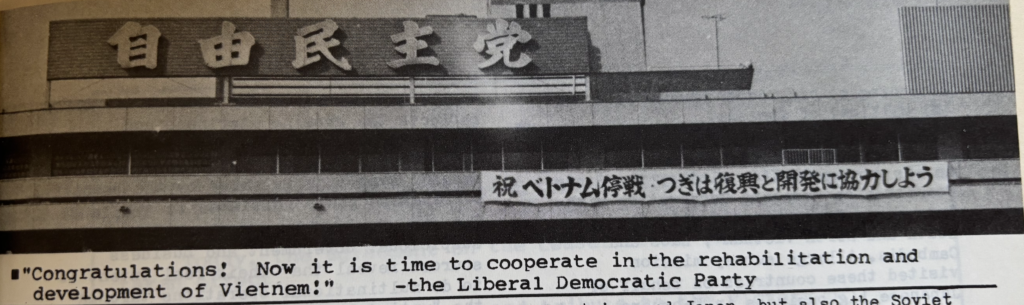

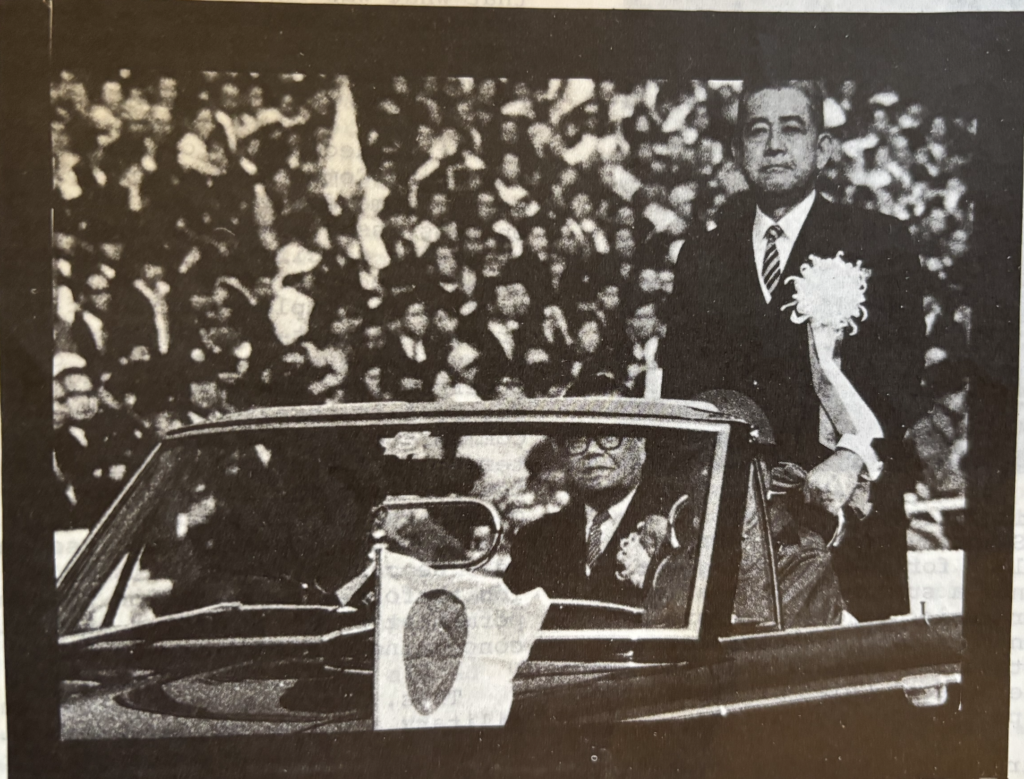

Japan doubled down on its support after the US Marines landed in Vietnam in 1965. By then, its prime minister was Eusaku Sato, Kishi’s brother. He became a big-time cheerleader for US in Vietnam. When President Johnson began bombing North Vietnam in 1965, Sato could hardly contain his enthusiasm. In one visit to Washington, D.C., he endorsed the U.S. efforts to stop communism at a speech at the National Press Club. He was so emphatic about his support for the war in his meetings with President Johnson that he became known as LBJ’s favorite foreign leader.

But to millions of Japanese, Sato was a warmonger. Their land was being used as a base to bomb and lay waste to another Asian country, and many felt ashamed. The rage was compounded as Japanese commuters watched long trains of jet fuel being shipped to US bases moving through Tokyo (I recall seeing these black cars slipping through crowded stations like Shinjuku and feeling embarrassed and sickened). As Japanese reporters began sending back stories from South Vietnam of the extensive U.S. bombing and shelling throughout the country and the brutality of General Westmoreland’s search and destroy operations, public opposition grew to the war and Japan’s complicity in it.

Most of the early demonstrations were organized by the “old left,” made up of the Communist Party and its affiliated unions. By 1967, the war was a deeply divisive political issue in Japan and a rallying cry and symbol of the Japanese new left and the Zengakuren student movement. That year, two events brought many ordinary Japanese into the streets and sparked a new citizens peace movement: the desertion of sailors from the USS Intrepid, a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier, and a port call to the southern port of Sasebo by the USS Enterprise, the nuclear-powered carrier that was leading the airborne assault on North Vietnam. This movement, new to Japan, was much broader than the leftwing student and labor groups and included housewives, environmentalists and farmers.

The best known of the antiwar organizations was Beheiren, “Peace in Vietnam Committee,” led in part by Muto Ichiyo, who I mentioned earlier. It was organized in 1965 to create links between the Japanese movement and antiwar forces in the US and Europe. Beheiren came to national attention when the four US airmen from the Intrepid deserted their posts in the US Navy base in Yokosuka and sought assistance from the group, many of whom spoke English.

Eventually, hundreds of American deserters escaped from the killing fields of Vietnam and Southeast Asia through Japan, many of them ending up in the Soviet Union and Sweden. Beheiren housed the deserters and kept them out of the clutches of the U.S. Naval and Army intelligence. Eventually, the deserters were escorted to northern Japan, where they boarded fishing boats and other vessels that took them to the Soviet Union. When the US demanded that Japan crack down on this underground railroad, the Japanese government had to confess that they had broken no laws: it was perfectly legal to escort a foreigner across Japan and help get them board a boat out of the country. It was also during this time that US antiwar activists such as Jane Fonda and the late Donald Sutherland, began funding GI Coffee Houses at US military bases in Japan and Okinawa to work with active duty GIs who were protesting the war.

Labor unions allied with the Socialist and Communist parties as well as the New Left were also deeply involved in the antiwar movement. In 1968, when massive protests against LBJ’s escalation of the war shut down the city of Tokyo, leftwing train conductors whose union was affiliated with one of the New Left groups collaborated with the student-led protests to shut down several commuter lines, paralyzing the city. Unions were especially active in US-occupied Okinawa. Workers at major US bases went on strike several times during the war, once during a wave of US bombing raids on North Vietnam. In response, the US military flew in top officials of the AFL-CIO to help break the strikes.

The Japanese movement culminated in 1969 with massive demonstrations against the renewal of the US-Japan Security Treaty. They are still the largest protests I have ever seen in my life. During that year, dozens of universities were seized and shut down by students affiliated with one of the two factions of the Zengakuren. One of them was International Christian University in western Tokyo, where my father worked as an administrator. It was closed down for over two years until Japanese police were called in to end the strike (after my anguished antiwar dad had left his job). Protests in Japan continued through the 1970s. One of the largest took place in 1973, when the aircraft carrier USS Midway was homeported in Yokosuka for the first time.

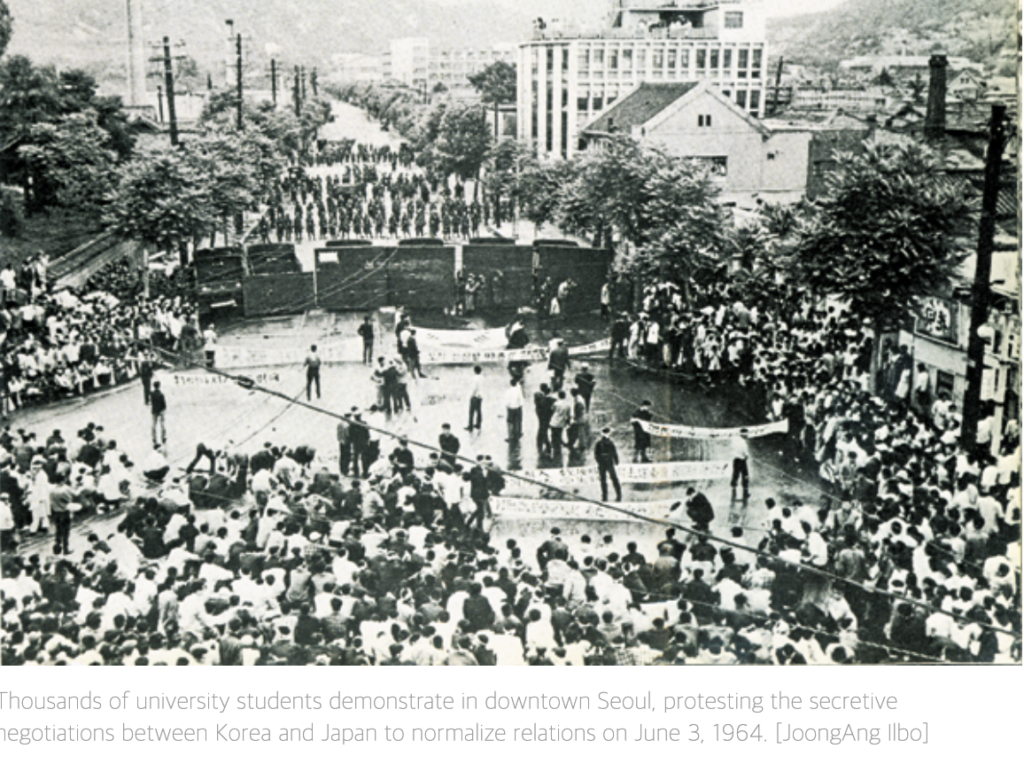

SOUTH KOREA’s ANTIWAR MOVEMENT. In 1960, Syngman Rhee, the Korean leader since 1945, was overthrown in a popular revolution. The US was tired of his rule (as well as his hatred of Japan) and supported the new liberal government by flying Rhee out of the country in a CIA aircraft. Over the next year, Koreans continued their citizen revolt by calling for a neutral, unified Korea without foreign armies on their soil and seeking justice for the thousands of innocent civilians executed by the Rhee regime during the Korean War. But everything changed in 1961, when Park Chung Hee took over in a military coup. In 1965, under pressure from the US, he signed a normalization treaty with Japan. Thus began South Korea’s antiwar movement.

The treaty was signed amidst massive demonstrations and another declaration from Park of martial law. One of the protest slogans was “The US is not our master.” It was spot-on, because by 1965 the US had sought the treaty as it was getting bogged down in Vietnam and needed military help from South Korea and economic assistance from Japan. That year Park sent the first Korean troops to Vietnam; they eventually numbered over 300,000. They were responsible for many massacres and in some towns and villages were considered worse than US troops. By 1973, 3,806 Koreans had been killed in combat and 8,779 wounded. During the war, those statistics were never made public. To hide the soldiers’ role from the Korean people, the dead were returned secretly to Osan US Air Force Base; the families were then notified and given indemnity. Foreign reporters were prohibited from photographing the returning dead and any reports of atrocities by Korean soldiers were censored.

Public protest in this situation was dangerous. In 1972, fearing a total US military pullout from Korea, Park declared martial law again and transformed South Korea into a torture and surveillance state. By 1973, South Korean jails were filling up with peasants, workers, and students. Even in Park’s home town, peasants demonstrated against government confiscation of land to build factories. Their leaders were arrested and tortured and charged with being “communist agents.”

Yet the democracy movement would not be silenced. In 1973, the opposition leader Kim Dae Jung (elected president in 1997) led South Korean resistance to military rule. That fall, over 60 demonstrations against Park took place. A statement by Christian youth summarized the resistance perspective: “Thinking of none but itself, Japan’s economic takeover is not only making Korea a serving maid to Japan’s economic advantage, while bringing about the economic ruin of our people, but is also increasing the Korean government’s corruption and dictatorship.”

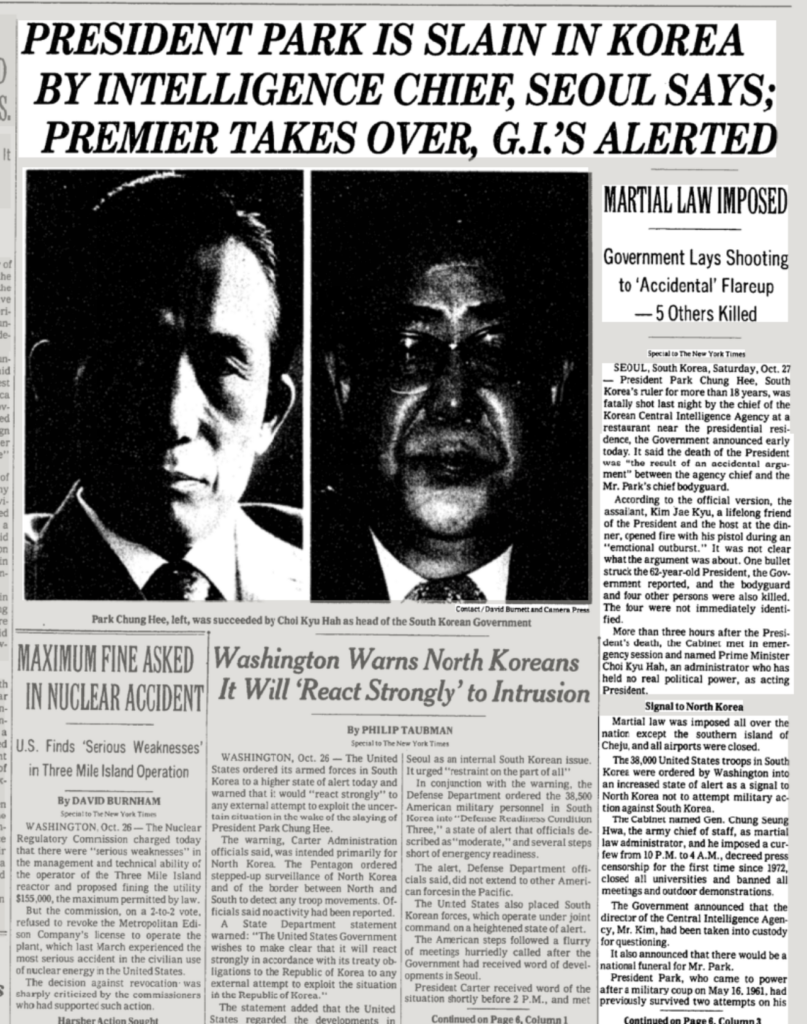

In October 1979, Park was assassinated by the director of his own KCIA. Over the next year another general – one of the many Korean soldiers trained by the US to fight in Vietnam – seized power in a rolling military coup that began in December 1979 with his takeover of the Korean Army and climaxed on May 17 with the expansion of martial law throughout the country. Over the next few days, General Chun Doo Hwan slaughtered hundreds of people in the city of Gwangju, sparking the first armed revolt in the South since the Korean War. But the US covered up his crimes and threw its support to him, as did the ruling LDP leaders in Japan. But, inspired by Gwangju, Korean citizens organized and fought against the dictatorship, finally winning their democracy in 1987.

Under Korea’s new system, the press was now free to investigate the past. Thus began the South Korean movement against the Vietnam War and in support of reparations for the Vietnamese people who were the victims of South Korean military violence. In 1999, reporters from the progressive newspaper Hankyoreh made the first findings, including an incident from 1968 in which Korean Marines assembled around 70 resident of the village of Phong Nhi and executed them. Similar massacres of civilians by South Korean troops occurred in around 80 places during the Vietnam War, with the death toll estimated at around 9,000 Vietnamese civilians.

Koreans organized several organizations to support the Vietnamese victims, including the Civil Society Network for a Just Resolution to the Vietnam War Issue and the Korea-Vietnam Peace Foundation. They travelled to Vietnam to visit sites of the massacres and meet victims. In 2020, they helped one Vietnamese victim file a damages lawsuit in Seoul, and in 2023 a Korean judge approved the veracity of her claims and ordered the government to pay her around $23,000 in restitution. Many other claims like that have been made, but the current Korean government of Yoon Suk-yeol has refused to pay, and is appealing.

In the end, the Japanese and Korean movements were effective in building democracy and reining in US power in their countries. Yet today, nearly 50 years after Vietnam’s liberation, both countries are in a three-way military alliance with the US that continues to dominate Asia and threatens war with China and North Korea. The resistance continues, however. In Okinawa, where the governor was elected on a platform to remove the US Marines, protests continue daily at Henoko, where the LDP government is building a new base for the Marines. Many of the Koreans active in the democracy movement of the 1980s are still speaking out against US military policy in Asia and the Pacific. Both movements have built strong people-to-people ties with Vietnam.

In contrast, the US antiwar movement (in my opinion) abandoned Asia after the Vietnam War and left the region to be defined for Americans by the Pentagon and the far right. That was a historical error of huge proportions and has resulted in the militarized US policies we see today throughout Asia and the Pacific.

Tim Shorrock is a journalist and writer based in Washington, DC. He grew up in Japan and South Korea during the Korean and the Vietnam wars and was actively involved in the antiwar movement from the time he was in high school. During the 1970s, he was active in the Indochina Peace Campaign in California. Starting in the 1980s, Shorrock reported extensively on the Japanese and Korean labor and peace movements and broke important stories about the interventionist role of the US military and the CIA in both countries. In 2015 he was given an honorary citizenship by the city of Gwangju for his reporting on the secret background role played by the US government and military in the events surrounding the 1980 Gwangju Democratic Uprising in Korea and the imposition of martial law by the infamous general Chun Doo Hwan. This year, the city’s archives published a three-volume book translating into Korean the 3,000 US documents Shorrock obtained under the Freedom of Information Act to write his stories. Over the past 45 years, he has published in numerous US, Korean, and Japanese publications, including The Progressive, Salon, Hankyoreh, Sisa Journal, Newstapa, and Sekai. He was a correspondent for The Nation magazine from 1983 to 2023 and is the author of SPIES FOR HIRE: The Secret World of Intelligence Outsourcing. Shorrock is now working on a book about the tripartite US military alliance with Japan and South Korea and last visited Japan, Okinawa, and South Korea in 2023.

Website: https://timshorrock.com

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/c/DMZEMPIRE

Twitter/X: @TimothyS