Covering Women Cross DMZ as a Reporter

A Photo Record of the Journey that Kicked Off a Movement

By now, I hope many of you have seen Crossings, the wonderful film from Deann Borshay Liem about Women Cross DMZ, its founder Christine Ahn, and their historic walk from North to South Korea in the spring of 2015. As I’ve observed, this organization’s work for the last eight years has single-handedly put the issue of a permanent peace in Korea on the US foreign policy agenda for the first time since the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950.

Over the past week, Women Cross DMZ’s work for peace – along with the Korea Peace Now network and other NGOs – was finally recognized in the US media when they held four days of activities in Washington, DC, to press for a permanent peace treaty to end the Korean War once and for all (see this great coverage at the Washington Post, NBC, and PBS News Hour). And, like its work from the beginning, Women Cross DMZ and the entire peace movement has been subjected to ugly smears and McCarthyite attacks, this time from Newsweek, the Wall Street Journal, and National Review (all of whom are apparently petrified of a women-led peace movement for Korea).

I happened to be in Korea at the time of the famous crossing in 2015, and got up to the DMZ just before Christine and her crew were driven – at the insistence of US Forces Korea, which runs the misnamed United Nations Command – across the border in a bus. I’m proud to have been a witness to this event and also to have authored the only article in the mainstream press at the time (in Politico) that did not try to undermine them with red-baiting innnuendo. Last week at the Korea peace conference in DC, I was talking about my experience with Ann Wright, the retired Army colonel who was on the crossing. We agreed it would be a cool idea for me to post pictures of the event from my perspective as a journalist.

So in this piece, I’ll use my photographs from the day to show what it was like to see the crossing of the DMZ from the other side – the media side, that is. For me, it was a revelation.

I first heard about Christine Ahn’s plans for the DMZ about two years earlier, when she told me of her dream of women taking over the job of peace-making and bridging the rivers of division and war in Korea. I watched with amazement as she cleared the way by negotiating directly with the governments of North and South Korea and the American military officers of the UN Command (explained in my Politico article). It was depressing to hear that both South Korea and the US had opposed a traverse by foot cross the border area – something that was not unprecedented – while the North had approved. By the time the march got underway in 2015, I was ready to cover it.

My trip to Korea began in Gwangju, where I’d been invited by the city to accept their offer to make me an honorary citizen for my journalism on the US background role in the Gwangju Uprising of 1980. I spent several great days there, speaking at press events and meeting new friends and comrades. But all the time I was keeping an eye on Christine & Company as they made their way into North Korea and down the peninsula. One day there was a photograph in the Korea Times showing they were about to cross. I got up to Seoul right away.

Seoul was as interesting as it always is.

Downtown, the bereaved families from the 2014 Sewol ferry disaster – thanks to the progressive city government – had set up a permanent encampment on the main avenue that cuts through Seoul. The great Admiral Yi Sun-sin, whose “turtle ships” had defeated the first Japanese invasion of Korea in the 1590s, seemed to watch over the tent city, which the conservative national government of President Park Guen-hye did not like. One evening, a friend drove me to find my family’s old house in appropriately named “UN Village,” where I lived in 1960 and 1961. My house was long gone, however, replaced by very expensive condominiums looking over the Han River, as we once did.

The next morning, I rounded up my crew – Stephen Wunrow, my photographer for the day, and Cho Tae-gun, my guide and all-around source of information. In Tae-gun’s car, we headed north towards the DMZ, only to find the road blocked by the military as we approached the border. Young South Korean MPs checked all of our passports and IDs. None of them knew any details of what was about to unfold in the DMZ – not even this serious-looking dude of much higher rank. Eventually, the roadblock opened up and we hit the road towards Paju (click through the photos below).

Only the Americans Had a Clue

Once we got to the customs house at Paju. where traffic going to and from the North-South Industrial Zone in Gaesong just north of the border used to pass, we finally began to see American soldiers from the UN Command (which reports to the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the Pentagon). As our vehicles approached, they were checking out the bus that was about to head north through the DMZ to pick up the Women Cross DMZ delegation as they approached from Pyongyang. It was only when I uploaded these shots for this story that I noticed it was the same bus that came down about an hour later with the women delegation of peacemakers.

We then arrived at the Customs House at Paju, where the delegation was going to enter South Korea. Next to it was a large guardhouse with a roof overlooking the road leading into the DMZ. There, we and the other reporters waited for their arrival and talked to the only official who knew anything about the crossing. D.E. “Dan-O” McShane, a Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. Navy and a Joint Duty Operator at Panmunjom, informed us that Women Cross DMZ would come across the border on a bus, as earlier agreed. I asked why the UN Command and USFK had refused to allow the women to walk, as they had wanted. “Security reasons,” he said, without elaborating.

McShane, who was constantly on a cell phone with the US command in the Joint Security Area of the DMZ, was correct about the timing. Suddenly, we saw the bus turn the corner and hit the road into the Paju customs area. This was getting exciting! With my crew, we all ran down the stairs into the large hall where the women were about to make their entrance.

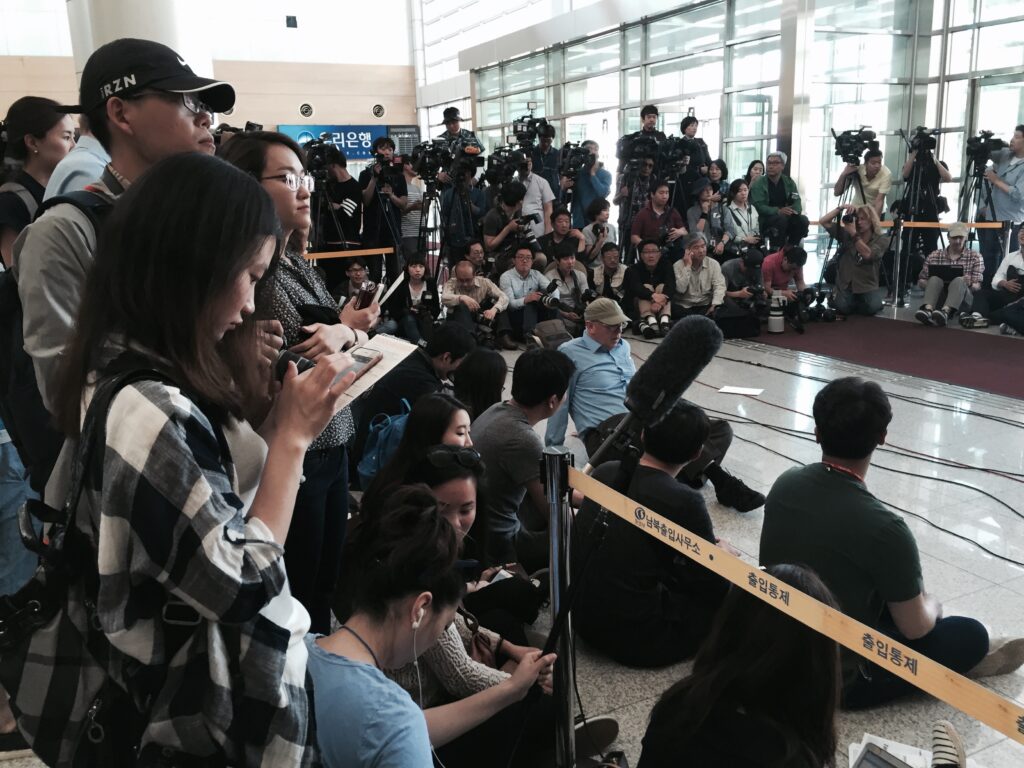

Inside were dozens of reporters, mostly Korean, but also British (BBC and Reuters) and one or two Americans. The Washington Post, always eager to cover anything about North Korea, sent an intern. We waited for the women to come through the big doors…and waited and waited. Finally, there was movement, and out they came. It was a glorious site to see all these great women in their white dresses beaming with joy as they emerged from South Korean security (where Christine Ahn and Medea Benjamin had to sign statements saying they would not violate the National Security Law while in South Korea). Gloria Steinem made the opening statement for the group and then took a few questions from the reporters. A few, notably the reporter from BBC, were downright hostile, demanding to know why they had not denounced North Korea’s record on human rights during their visit.

As the BBC reporter and others kept up their pestering, Mairead Maguire, the famous activist and Nobel Peace Prize winner from Ireland, took the microphone. Looking straight at the British reporter demanding answers, she gave one of the most eloquent speeches I’ve ever heard on the connection between war and human rights. During the “troubles” in Northern Ireland, she said, there was violence, bombing, torture, and human rights violations by both the IRA and the British. But once a peace was negotiated and the two sides normalized their relations, those violations ceased. “Ending war is the prerequisite to establishing human rights,” she said, as I recall. It helped calm the foreign reporters who seemed to be under pressure from their editors to make the women look as wacky as possible; they failed.

A Reunion Upstairs

All this time, I was looking for Christine Ahn. It turned out she was in the back of the crowd so she wouldn’t be barraged with hostile questions about North Korea. While in the North, she’d made a comment to the government-run news service about Kim Il Sung, and it had been deliberately twisted by the North Korean reporter; her misquotes were then picked up by AP and other wire services and printed in South Korea. I finally found her upstairs in the customs house and we had an emotional reunion together. It was great to see her and Medea Benjamin of Code Pink and meet the other members of her delegation. As someone who had first seen the DMZ in 1960 and had been working on Korean peace issues since the 1970s, I was very proud of all of them for taking this giant step. Those were bright moments I will never forget.

The March to Imjingak

After their reception, Women Cross DMZ headed out by bus again to the outskirts of Imjingak, the park where South Koreans go to remember the Korean War and peer into the North. There, they were met by hundreds of South Korean women, nuns, and peace activists, all of them joined together in the quest to end the Korean War and bring peace to their land. I’ll end my story with these pictures, cops, defector-protestors, and all. They express far more than words the significance of this historic crossing in 2015. Eight years later, they’re still going strong!