Note: This was reported and written in 2018, at a time when a peace agreement between North and South Korea seemed within reach. Seems like a long time ago.

In my latest article, published today by The National Interest, I ask the question: “Can the United Nations Command Become a Catalyst for Change on the Korean Peninsula?”

It’s based in part on a recent speech in Washington by a Canadian general who was appointed last May to be deputy commander of the US-controlled UNC – the first time a non-American has held that position. Based on my impression of recent events in Korea – including today’s UNC-brokered, astounding announcement that North and South Korea have terminated “all land-, sea-, and air-based hostile activities” in the border area – I believe that that the Command is playing a useful role in the Korea Peace Process.

Now that the Trump administration and South Korea appear intent on negotiating a disarmament deal with the DPRK and the two Koreas are moving forward on their plans to end the Korean War and create an environment for peace and reconciliation, the U.S.-run command appears to be shifting from being a tough enforcer of the armistice agreement that ended the fighting in 1953 to becoming almost an neutral arbitrator between North and South.

I went on to show, in detail, how that is being done and the other steps towards demilitarization the two Koreas have taken in consultation with the UNC in recent weeks. But I also wrote this to lay out how the UN Command in Korea operates and to provide a little history.

At present, the primary function of the UNC is to oversee and enforce the armistice in the southern half of the Korean peninsula by monitoring the Military Demarcation Line that marks the aerial boundaries between the DPRK and the ROK over land and sea.

As part of this responsibility, it also controls all movement across the border and through the DMZ (it’s that authority that allowed the UNC to review the inter-Korean military agreement). The UNC is also responsible for dialogue with the the militaries of North Korea and China.

The command is reinforced by a UNC Security Battalion, which patrols the Joint Security Area in Panmumjom, and a UNC Liaison Group, which is composed of defense attaches from the sending states (“It’s a lively group,” said General Eyre, adding that it meets with the UNC on a weekly basis).

Here’s what I consider one of the least understood aspects of the UNC – it’s direct link to US bases in Japan and Okinawa as well as the Japanese Self-Defense Forces.

The command’s most important component is the UNC Rear, which is based in Japan. Under its mandate, which is made possible through the U.S.-Japan Status of Forces Agreement, the UNC Rear would have the responsibility of facilitating U.S. and UNC mobilization to Korea in case of a second Korean War.

Over the past year, UNC Rear has been instrumental in organizing air and sea surveillance operations that monitor North Korea’s alleged evasion of the sanctions imposed by the UN Security Council. Those operations, which include Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Forces, have continued until the present.In September, even as the DPRK and the ROK were moving forward with their peace process, Australia and New Zealand joined the U.S. and Japan in maritime surveillance operations.

The US Marine Base at Futenma is part of this structure.

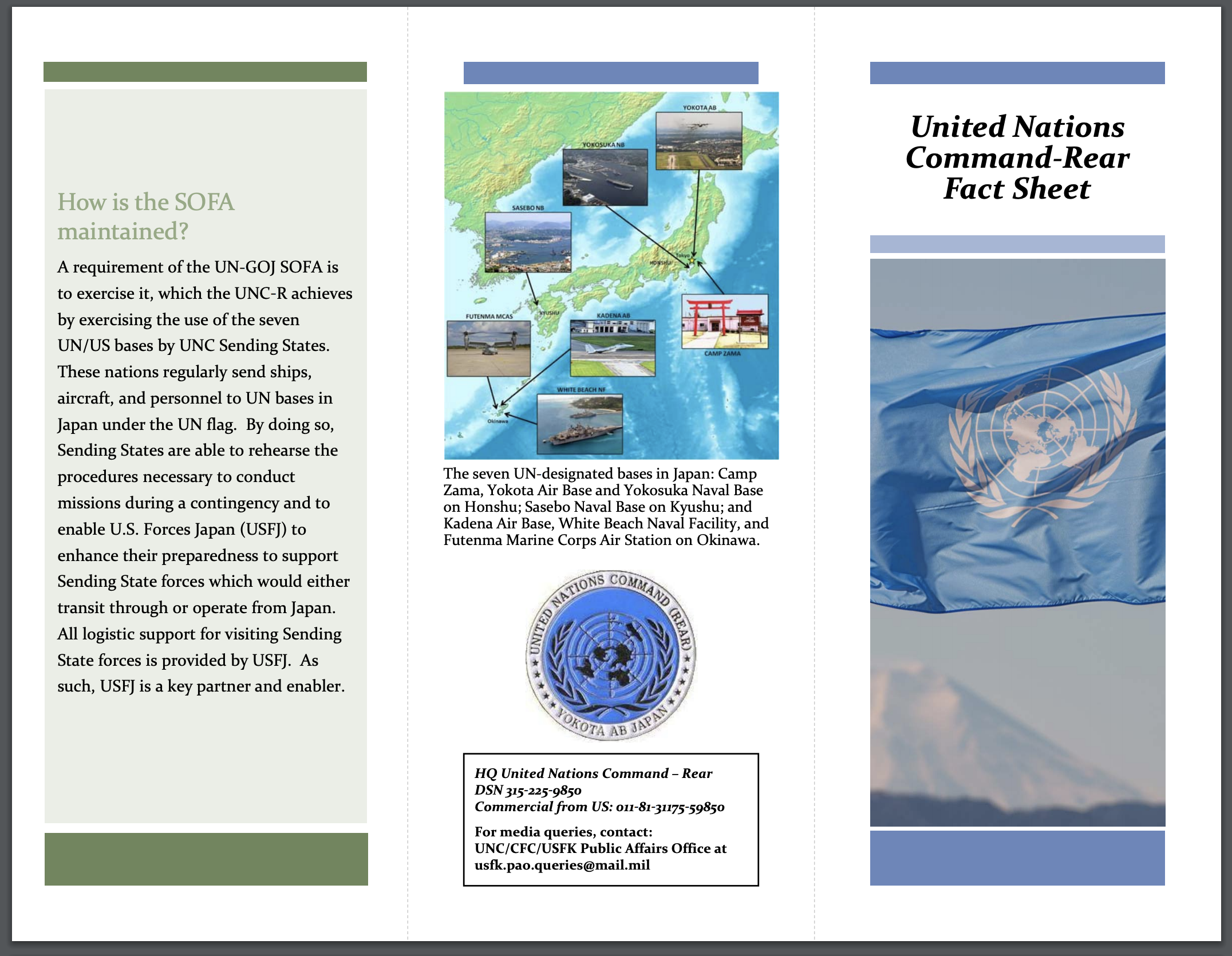

The UNC Rear, which is based at Yokota Air Base in Japan, includes seven American installations. They include the massive U.S. naval base at Yokosuka as well as Sasebo naval base in Kyushu and two of the most important U.S. bases in Okinawa, Kadena Air Base and Futenma Marine Corps Air Station , according to an official UNC Rear publication.

These bases, General Eyre said, that would “coordinate the sustainment of coalition warfare supporting the CFC and USFK” if hostilities were to break out in Korea. As tensions escalated last year over the DPRK’s nuclear and missile tests, the UNC and its sending states had “serious discussions” on potential actions that would have originated at these bases, he added. But the sudden change in atmosphere, triggered by Kim Jong-un’s declaration that he had completed his “nuclear force” in November 2017 and the peace talks that President Moon initiated during the Olympics, altered the UNC’s approach.

Futenma, of course, has been the bane of Okinawa’s existence for decades and is at the heart of the long-running dispute between the US and Japan over the American base structure on the island. As I posted on Twitter earlier today, these bases show how Japan is inextricably tied to any US war plans for Korea (described in my article in The National Interest), and why it might be targeted by the DPRK’s missiles as it was in several North Korean tests last year.

But we recently learned how important strategically Futenma alone is to US war plans from William Perry, the former secretary of defense who almost launched a strike on the DPRK in 1994. Outside of the Japanese language press, I was the only journalist to report on Perry’s description, in LobeLog. Here is what he said (the italics are mine):

A peace settlement in Korea would immediately eliminate the strategic rationale for the controversial US Marine base in Futenma, which has been a sore point between the US and Japan for decades and which a majority of Okinawans adamantly oppose.

That’s because the US Marines at Futenma are stationed there as the first line of defense if North Korean forces ever invade South Korea, said Perry, drawing on his experience in 1994. “The whole purpose of US military planning relative to North Korea is to get reinforcements in very, very quickly to stop North Korean forces before they get to Seoul,” he said. “A key component of that is the forces at Futenma—the rapid reinforcement of both land and air forces are key parts of that plan.”

Therefore, if a peace process involving both the United States and South Korea eliminated the threat of a North Korean invasion, US forces in Futenma and elsewhere in Okinawa could be “not just relocated but removed,” Perry argued. “That’s not going to happen obviously very soon. Whether it’s a serious prospect depends very, very much on the summit meetings.”

Posted below is a UN Command Rear Fact Sheet posted on the Yokota Air Base website.