Rushing Towards Remilitarization Since the Korean War

Last month, as I’ve reported and the mainstream media has studiously avoided, Japan took a giant step towards becoming what the United States considers a “normal nation.” It did this by giving its “Self Defense Forces” the ability to strike enemy bases overseas for the first time since Japan’s surrender in 1945. I described that development on these pages on December 23 in an article entitled “Japan Crosses the Rubicon” that, thanks to Antiwar.com, received a record amount of traffic on my website last week.

As I mentioned in that piece, the Kishida government’s “new” policies largely originated in Washington, which has been pushing Japan to become a bona fide military power for over 40 years. It also helped to revive its army during the Korean War by starting the Self Defense Forces, known as the SDF, as a “national police reserve force.” Washington military industrial think tanks such as the RAND Corporation consider the SDF critical to US strategy against China and make great efforts to raise its visibility in Japan. In my next article in this series, I will be tracing the history of the U.S. pressures on Japan to rearm, starting in the 1970s.

While I complete my reporting, I want to bring you this article on the origins of Japan’s SDF from a 1979 edition of AMPO Magazine. It was founded during the Vietnam War by radicals seeking to link their antiwar movement with allied movements in the United States and Europe (“Ampo” is short for the US-Japan Security Treaty, the primary target in the 1960s of the Japanese left, as defined in the chant “Ampo hantai!” – Against Ampo! – that was heard during every major demonstration in Japan from 1960 to 1970.

I was associated with AMPO in the 1980s and 1990s and helped distribute it for a time as its U.S. representative. The magazine was founded by members of Beheiren (Citizens Federation for the Peace in Vietnam) and published by the Pacific Asia Resource Center (PARC) in Tokyo. It was a constant source of information about Japan’s role in the US empire in Asia and peoples’ movements throughout the region.

Fujii Haruo, who wrote this 1979 piece, was one of AMPO’s (and Japan’s) best military analysts (read about his revelations here). His history of the SDF is both penetrating and prescient. Most important for American readers is the link he draws between the creation of the SDF and the Korean War, when Japan began its slow ascent as America’s Cops in the Pacific. Below, I present his main points and a downloadable PDF of the original article.

UPDATE: Before getting to Haruo’s piece, it’s important to ask: how was the SDF financed by a Japanese government that, only five years before, had renounced war and watched as the United States dismantled its enormous military and war industry?

The answer is, secretly, through a huge, hidden fortune of gold and other treasure seized by the U.S. military from Japan in 1945 and controlled by General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of the U.S. Occupation Force. That treasure, eventually worth billions of dollars, was used to influence Japanese domestic politics for decades. It is now known as the “M Fund.”

Here’s the story, as told in 2003 by Sterling and Peggy Seagrave in Cold Warriors: America’s Secret Recovery of Yamashita’s Gold, published by Verso:

In 1950, when the Korean War started, most U.S. forces in Japan were rushed to Korea, creating a security vacuum. Because the postwar constitution prohibited setting up a new army, the M-Fund secretly provided over $50 million to create what was characterized as a self-defense force. When the occupation ended in 1952 and Washington and Tokyo concluded their joint security treaty, administration of the M-Fund shifted to dual control, staffed by U.S. Embassy CIA personnel and their Japanese counterparts, weighted in favor of the Americans….The M-Fund council interfered vigorously to keep Japan’s government, industry, and society under the tight control of conservatives friendly toward America.

I’ll be posting more on the M-Fund, including excerpts from the work of the late, great Chalmers Johnson, later this week. Meanwhile, let’s return to Haruo and the SDF.

The rise of Japan’s Self Defense Force and the Korea Factor

AMPO, Vol. 3, No. 4, 1979

By Fujii Haruo

Japan’s restablished military – the Self Defense Forces – is, like the armed forced maintained by any country, designed to protect the present Japanese ruling system – i.e., monopoly capitalism.

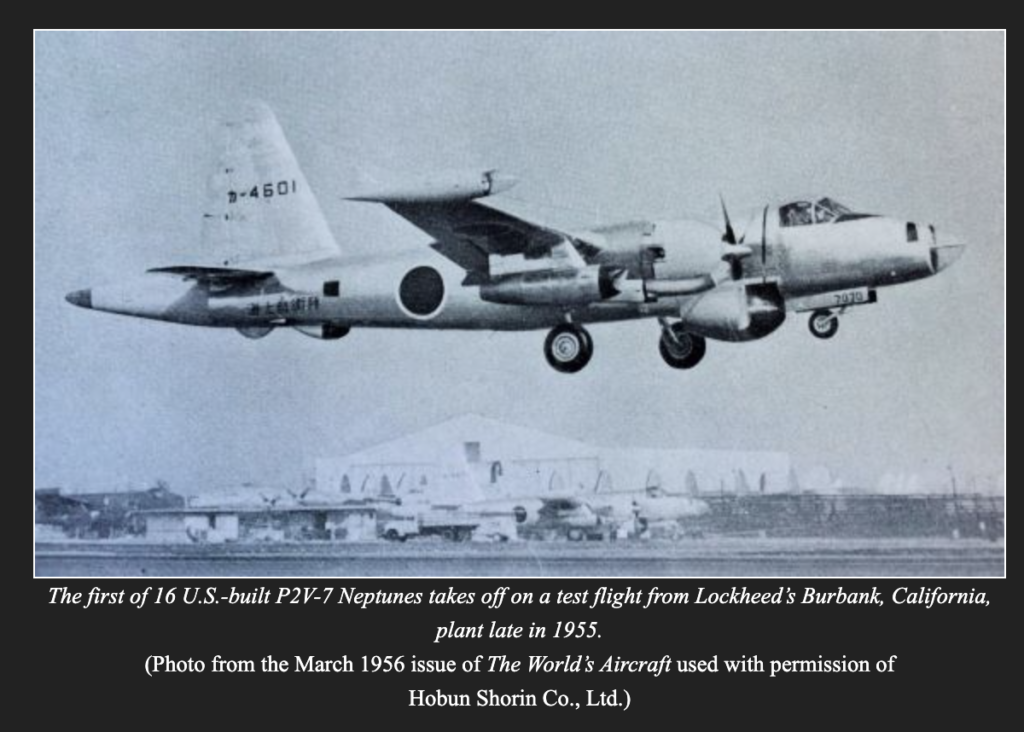

Due to its defeat in World War II, Japan’s “great imperial army” was dissolved. Immediately after the outbreak of the Korean war in 1950, however, General Douglas MacArthur, Commander-in-chief of the occupation army, ordered the Japanese government to establish a national police reserve force.

An immediate duty to be fulfilled by the police reserve force was to engage in maintenance of public peace in in Japan, since the U.S. troops stationed in Japan for that purpose were dispatched to the Korean peninsula. During the conflict in Korea, Japan served both as a dispatch base for U.S. operations in Korea, and as a supply base. U.S. military headquarters for the Korean war were located in Japan, there were many U.S. bases on Japanese soil, and the families of U.S. soldiers were living here. Not only was it the task of the police reserve force to protect them, it was also expected to eventually develop into a new Japanese army.

The Self Defense Forces (SDF) comprised of Ground, Maritime, and Air forces, were created according to the 1954 reorganization of the police reserve force, and were given the additional task of defending the national against foreign attack. In other words, regardless of its name, the SDF actually took on the same functions as the militaries of other countries.

The role of the SDF was to combat both domestic and foreign enemies, and to achieve these ends, it was to be mobilized both for external defense and internal security. In this way, a military was revived in Japan, equipped with both a military function against foreign countries, and one to maintain domestic peace and order by fighting against the enemy within the structure of Japanese monopoly capitalism, i.e., the Japanese people themselves…

[By 1979], the national defense budget amounted to 2 trillion, 400 billion yen, the 8th largest in the world. The countries superceding Japan in terms of their military budget [were] the five nuclear-armed ones, together the West German and Saudi Arabia. The total strength of the SDF [was] 240,000 men consisting of 155,000 men in ground forces, 42,000 men in Maritime forces with war vessels totaling 220,000 tons, 44,000 men in the Air force with 750 aircraft. Japan was thbus equipmmed with the strongest, most modern arms in the world in terms of conventional weaponry, and quality-wise [was] the strongest in Asia….

Present Focal Point: The Korean Peninsula

From 1958 to 1960 the first-phase defense power reinforcement plan was carried out, through which the framework of the SDF as a military was built. With the conclusion in 1960 of the new Japan-U.S. Security Treaty (a military alliance) as a start, the SDF’s external function was defined and strengthened. The focus of its external task was then directed towards the Korean Peninsula.

It was in 1963 that the Defense Agency’s Joint Staff Council confidentially conducted what became known as the “Mitsuya Study.” This study was designed to examine measure the SDF and Japanese government were to take, based on the assumption that a second Korean War would break out. The then U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense Roswell L. Gilpatric [who served from 1961 to 1964] stated around that time that he would expect Japan “to be equipped with enough monitoring power to protect the area, including a part of the Korean Peninsula, in the future.”

The U.S. used Japan during the Korean War as a sortie and supply base. For the U.S. Japan and South Korea were one defense zone, and the U.S. forces stationed in Japan and South Korea were considered as one body. [emphasis mine]. It was under this perception by the U.S. forces that the SDF and South Korean military were developed. In the early 60s, the U.S. began discussing a large-scale cutback in U.S. troop strength in South Korea and adopted a plan which would encourage Japan to take over the responsibility.

With the conclusion of a Normalization Treaty between Japan and South Korea in 1965, the political, economic and diplomatic relationship between the two countries was strengthened. [On this development, see my 2019 article in The Nation, “In a Major Shift, South Korea Defies Its Alliance With Japan.”] Strong resistance among the Japanese people agaisnt a direct military tie-up, however, necessitated that the South Korean military and Japan’s SDF continue their cooperations only indirectly, with the U.S. military as mediator. In 1968, however, high military officials of both countries began visiting each other and a system of informaqtion exchange between the two was established.

In 1969, a U.S.-Japan joint communique was issues which stated that “the security of South Korea is important for the security of Japan itself,” thus placing upon Japan the expection that it would take over from the U.S. responsibility for South Korea’s defense. Then, between 1970 and 1971, one division of U.S. ground troops was withdrawn from South Korea…

[By the 1970s],then U.S. Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger stated, in appreciation of Japan’s efforts, that “Japan is already playing an indirect role in the defense of South Korea. The defense capacity provide by Japan’s air Defense Forc3 is effective not only for the Japanese mainland but for the defense of South Korea.”

Towards U.S.-Japan-South Korean Joint Defense

Since the late 1970s the SDF’s attitude toward relations with South Korea became even more clear and positive. At the end of July 1979 the then director-general of the [Japanese] Defense Agency visited South Korea, becoming the first to do so while in active service…

Following the July 1979 decision to freeze the withdrawal of U.S. ground troops from South Korea, Japan was further drawn into assisting in South Korea’s defense. This trend continued in 1980, with the appearance of the Chun Doo Hwan regime in South Korea, and the Ronald Reagan administration in the U.S. These reactionary governments [promoted] trilateral military cooperation, including Japan, requiring that Japan go beyhond mere sharing of expenses for U.S. troops, increased imports from the U.S., and extending economic aid to South Korea. Japan is now being drawn into a higher degree of cooperation vis-a-vis South Korea’s defense…

[For Japan to become a military power], the Japanese government, the Liberal Democratic Party and financial circles began actively working woward revision of the constitution to incorporate these militaristic changes. From the beginning of the 70, the government and the defense authorities have put much of their energy into forming a “national consensus” on the need to maintain the Self-Defense Forces. Then from 1978 they have tried hard to form a consensus concerning the actual use of the Self-Defense Forces…

That process climaxed in 2015, when the late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and the LDP pushed through a critical vote in the Japanese Diet to lift its 70-year ban on foreign deployments and, as The New York Times reported, give “Japan’s military limited powers to fight in foreign conflicts.” And now, 8 years later, the Biden administration has made the SDF and the “trilateral” U.S.-South Korean-Japanese alliance into the centerpiece of its anti-China Asia strategy.

Read Fujii Haruo’s full article in PDF format here.

In Okinawa there has long been an incongruous trade in US military themed souvenirs. These days there are also some bizarre Japanese Defense Force omiyage, including army and air force curry. This rehabilitation surprises me, since, for many war survivors, Japanese militarism was remembered with even greater loathing than its American counterpart.